In the wake of a more than two-year lapse in live performance events in Toronto (and everywhere), the 2022 iteration of the Toronto Performance Art Collective’s 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art felt particularly infused with a sense of intimacy and softness. Being together in space feels almost new again, vulnerable—like a relationship you took for granted only to realize its value once threatened to disappear. I welcomed this tender charge in the audience every night of the festival—an ineffable sweetness I have not encountered in some time.

Many of this year’s artists were originally invited to participate in the 2020 festival, but we all know how that went… Performing instead two years later, and in the face of an ever-present coronavirus environment, thematic traces surely surfaced—housing, race, bodies in space, memory, precarity, time, environment, and speculation. Yet, these peripheral themes never dominated or even emerged particularly clearly; rather, they floated like echoes across the festival. This was refreshing, as predetermined curatorial agendas have become somewhat en vogue (and Toronto seems particularly prone to curation that “defines” or attempts to provide clear rubrics of understanding—especially as it pertains to notions of place). 7a*11d’s curatorial strategy instead brought intergenerational artists and cross-disciplinary practices into relation through a series of embodied transmissions.

~ ~

Watching Alain-Martin Richard‘s Animal bichéphale [Two-headed animal] with my 2.5-year-old daughter, I keep thinking about a children’s book we often read called Sometimes I Feel like a Fox that introduces kids to the Anishinaabe tradition of totem animals as a way for them to explore identifying with non-human creatures. Not yet jaded by knowledge of displacement and gentrification processes, my daughter watches with rapt curiosity as the dapper animal, wearing a fox mask, black tailcoat and pristine white gloves, painstakingly picks up pieces of rubbish within a fenced off area and wipes each one clean with gentle care. Possessing both a fox’s attentiveness and a man’s sadness, Richard invites viewers into reflection on the “state of the territory”—climate emergency, corporate capitalism, alienation from nature… My child asks, “why is the fox cleaning garbage, mama? Is he making a house?” I reflect on the vastness of her simple questions and the shocking responsibility of answering them. He picks up a crumpled beer can, empty liquor containers, and discarded Nestlé water bottles.

Standing outside of the boarded up, to-be-developed 99 Sudbury building (once an industrial glass factory, recently a popular Toronto events venue), the performance confronts viewers with complexities of the site. Surrounded by condos, cranes, and scaffolding, reminders of development abound. Fox-man coyly paces the length of the abandoned building, traipsing over weeds shooting through concrete. He looks to the whirring train, the passing cars trespassing through land, eyes glistening in the sun. He places each trash object in a delicate pile, his sweet acts of cleansing gesture toward reciprocity, collective need, and grief.

![Alain-Martin Richard performs Animal bicéphale [Two-headed animal] in the 7a*11d festival.](https://7a-11d.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/amr_stwh_hc-1024x684.jpg)

Archer Pechawis‘ nōhtāwiy awa [this is my father] takes the form of an outdoor “workshop” in the not-so-distant future where participants learn how to fish for rats out of a sewer—a practice necessary due to changes brought on by climate change and the ruinous impacts of ongoing colonization. Folks in this future have been forced by circumstance to change eating habits, shift gathering practices, and make significant cultural changes. Using a bait of cheese and pepperoni, our guide carefully drops the lure between the sewer grates while eager students (audience members) circle around in the street lamp’s hazy glow. Sitting on a plastic milk crate wearing a LAND BACK t-shirt and tool belt holding skinning and filleting instruments, Pechawis holds his fishing rod steady.

Waiting for a rat to bite, our workshop leader implicates his own family by telling the story of how his father was once the Dean of St. Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay, British Columbia, a school that operated from 1894 to 1974. Eventually we learn that Pechawis’ father was embezzling money from the school and church and the family later left town. Weaving in and out of the workshop, personal narrative, and pressing environmental considerations creates a disjointedness that reflects the realities of colonial trauma for Indigenous (and non-Indigenous) people living in Canada, and we are reminded that the residential school experience doesn’t end. Sitting there, I keep thinking about Canadian Art magazine’s Fall 2017 issue that jaw-droppingly stated that Archer Pechawis was dead. I could not shake the reverberating irony of this major editorial error paired with watching him “fish for rats” in 2022. In response to the statement of his being falsely declared dead, Pechawis wrote:

I have had the opportunity to meet, work with, and learn from the giants who blazed the trail for us against seemingly impossible odds, combatting racism, incomprehension, and indifference to make a space for us in the larger Canadian art milieu […] Given this history as an Indigenous artist, it is especially disturbing to be erased by a mainstream (read non-Indigenous) publication that is the “preeminent platform for journalism and criticism about art and culture in Canada.” [1]

nōhtāwiy awa [this is my father] displays how erasure, colonization, and blatant disregard for land stewardship have created the conditions for—essentially—fishing for rats. Indeed, and as Pechawis stated, “it is a mournful thing to fish for a rat.”

![Archer Pechawis performs nōhtāwiy awa

[this is my father] at the 7a*11d festival.](https://7a-11d.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ap_stwh_hc-1024x683.jpg)

Deep in the Streets by Rita Camacho Lomeli collapses boundaries between everyday life and art (revisiting the persistent goal of the Fluxus movement) and plays on John Cage’s A Dip in the Lake. Each day, chance-determined locations are established as destinations to walk to by tossing dice, coins, or pulling pieces of paper from a hat. This walking meditation and attunement to synchronicities turns day-to-day life into art. Noises from bustling shops, overhead planes, whirring street cars, screaming ambulances, barking dogs—life is happening. An old man tinkers with a lawn mower in his yard and I see graffiti I’ve likely walked past dozens of times without notice: EVERYONE IS NUDE. Sun on my skin, birds chirping, porta-potties, construction workers, an officer giving a parking ticket… these experiences become it. The kismet of our colliding encounters in the Toronto streets activates a living, unofficial archive that operates through casual conversations, local art histories (Wendy Coburn used to live in this house…, so- and-so had a studio here in the ’90s…), emotions, gossip, boarded-up buildings. The more I pay attention, the more I am part of it.

When I walk into Lucky Pierre‘s one-on-one performance In the Future Something Will Have Happened, a large colourful banner assures me: Everything is going to be alright. I sit face-to-face with someone who reads me a list of probable things that will happen in one year—the number of breaths, blinks, subtle geographic shifts. An old lady on a bus will pass me and at the perfect moment we will lock eyes from out of her moving window. I answer a list of questions posed by the host who then scribbles each response onto a form, detailing my personal information: preferences, things I would like to accomplish, dreams I have. Then, I go on a very long walk with my guide, Heather.

I have read in the festival’s website description that the performance deals with themes of algorithmic control, so I project this idea onto my walking experience with Heather, who commands me to stop at certain points, nudges me to look at certain objects, to pay attention to particular actions, and sways me to walk fast or slow. This is a walk I can barely stand—being led by someone without knowledge of where I am going, when it will stop, and that is not on my terms, irks me. And yet, this is quite the way that algorithms function, like traps, outside of our control—you like (or dislike) this, and therefore probably this; your behaviour indicates this, which perhaps means this. When we finally return, I am asked more questions such as what does fear feel like in your body? What is a word you struggle to say? I am told that based on my experience today, an analytic “report” will be produced and mailed to me and I am promised that my information will not be shared or sold.

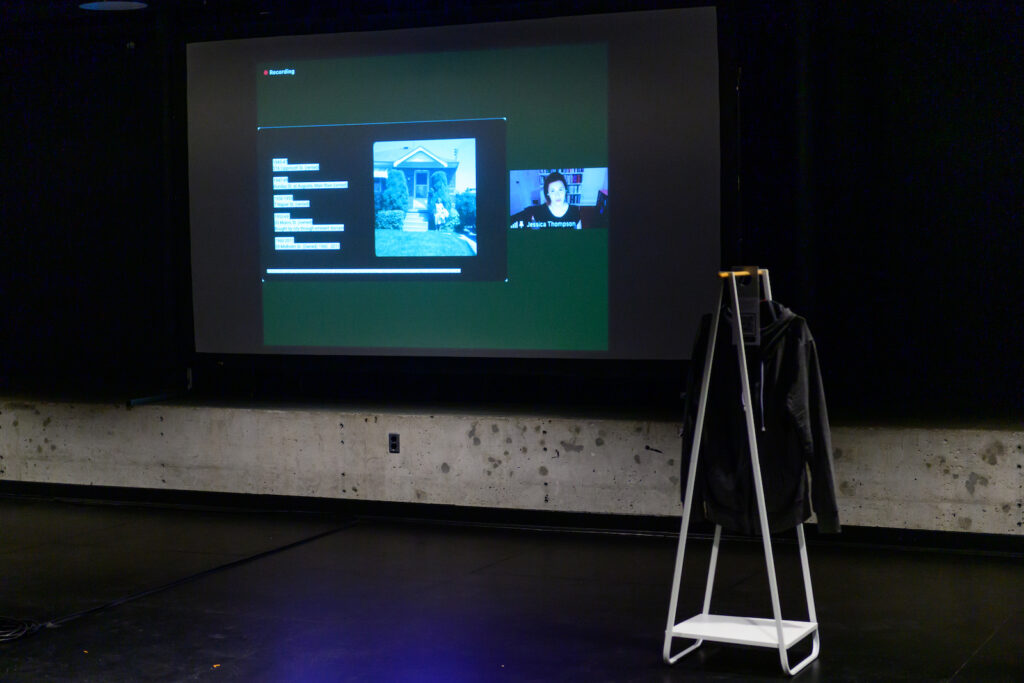

Positioning the body as site, Jessica Thompson’s wearable media project DoubleBind explores the duality of the hoodie, making apparent that this hyper-charged garment has different meanings depending on the positionality of its wearer. Following the shooting death of an unarmed Trayvon Martin by self-appointed neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman in 2012, the hoodie has gained widespread legibility as a symbol for practices of racial profiling and stereotyping that disproportionately inflict violence on Black individuals and communities. The hoodie has also become representative of protest against this injustice. Thompson’s kinetic apparatus is designed to be worn in two ways—either covering the wearer’s head or zipped into a collar around their neck. Depending on how and where it is worn, tweets are algorithmically generated and include descriptive content from Airbnb listings, local restaurant reviews and segments from the Black Panther Manifesto. Placing users in a performative situation wherein their choices are complicated by the knowledge that tweets will be visible to their social networks, thus sets politics upon the wearer (an imposition that often happens to Black people in the public sphere). Thinking about the (white) public desire to perform solidarity in the face of racial terror—to put on a hoodie and relate to blackness—whether on social media or to participate in an art project—reminds me of bell hooks’ “eating of the other” analysis that speaks to the insatiable fetishizing of the Black body that results in consumption of “the other” in white imaginaries through cultural and physical proximities. [2]

DoubleBind struggles in the context of a performance festival because the work is indecipherable without background information. The tweets themselves are not evocative enough to provoke meaningful public dialogue as they are mostly nonsensical. For folks who happen to scroll upon them, there are no strong references that could indicate the deeper resonances of this work. For example, a couple of my tweets: “A rotating pop-up shop opens on Ossington. The $ 1. 2 million for a good solution for the communities in this situation” and “Apartment On Queen st W. ROOM in Queen West. This new food shop on Queen West is getting a Rose and Sons.”

That said, in an era of intense virtue signalling, the risk taken by participants to relinquish control of their online identity, even briefly, is a powerful element. The conceptual rigour of this work is commendable and it without doubt succeeds (if you are privy to the details of the project) in illustrating how bodies and sartorial markers are inherently political.

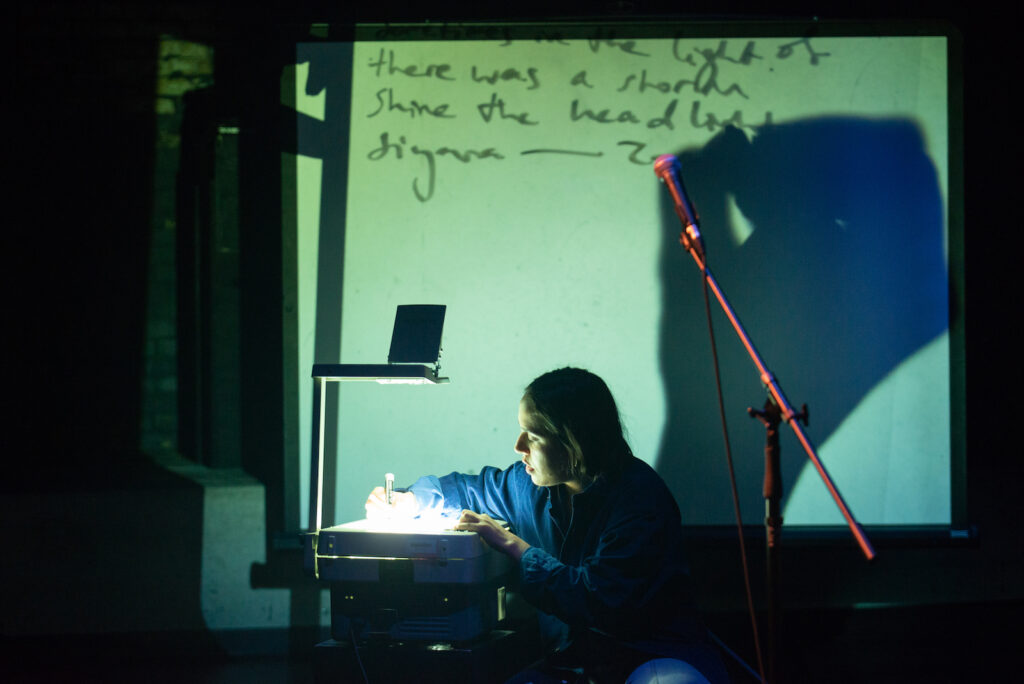

A boombox perched atop a table scattered with papers, files, photos, and other analog equipment set the scene for Jana Omar Elkhatib‘s performance reading Notes for an intervening time. Poetic refraction through layering of recorded voice foregrounds the limitations of listening across language and memory, and yet the inherent intimacy that remains across distance and time. Punctuated by gaps in understanding—like the slow stop and rewind process of transcription—a dreamlike palimpsest of recollections and reveries flood the stage. A cassette tape plays sounds of the domestic; stories, children laughing. The squeak of a dry erase marker on transparency paper teleports me to another version of myself. The audience becomes buried in the veneer of language, lost in the blurry fog of remembering. I crave to hear her voice and not the recordings; to see her eyes—and I wonder, why performance? While the personal particularities of this piece did not necessarily fan out to a larger collective knowing, its nostalgia still washed us ashore.

Because it became unfeasible for Taiwo Aiyedogbon to travel to Canada from Nigeria to attend the festival given the current long wait times for visitor visas, a video of Fragile Space (featuring Aiyedogbon) is instead projected and a score provided for two local artists, Claudia Edwards and Blane Solomon, to perform. A vivid screech of tape stretching and pulling booms from the speakers while two women clad in black stand in the middle of the room gazing into one another’s eyes. The tape alerts, FRAGILE! and the women begin fastening it to each other in small parts. Arms, legs, head, breasts, skin, necks, buttocks and whole bodies tethered by this marker of fragility. Audience participation is initiated, and people are urged (quite dramatically) to join in the taping. Cautiously at first, people trickle up to add tape to what now looks like a living sculpture. The actions become bolder as the momentum of participation grows—feet taped to the ground, heads taped together, mobility taken away. Soon, clear social dynamics emerge and take centre stage: a man ties the bodies together; a woman runs up and cuts them free. This cat-and-mouse dynamic continues for some time. Vulnerability is inherent when welcoming this kind of public participation, often becoming the focus of the work (think Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece), but this does not exactly land here. An overwhelming performative ethos of folks from the audience wanting “do something to help” feels trite. Near the end, a woman jumps up and tapes the scissors to her own body (“came to the rescue”) and ultimately centres herself as the work.

It can be hard to know who your real friends are—especially in the art world. Are your ideas being stolen? Has someone infiltrated? Do they really like you? Geneviève et Matthieu’s performance installation M. Gros [Mr. Big] transposes a police investigative technique into the paranoia of the contemporary art milieu in an attempt to solve a cold case.

Geneviève’s oversized blue floral bonnet and Matthieu’s calm looping guitar impress upon me like a dream: it’s like Little Bo Peep has lost her freaking mind; it’s the Yellow Wallpaper on steroids. A jumble of signifiers disorients and teleports viewers into an opulent fantasy in which to project their own narrative. Various shape-shifting characters are taken up while several scenes loosely play out in collaboration with clusters of lively objects. Assemblages of sculptural items ooze with animacy, ranging from brown phallic sticks dangling on ropes, religious iconography, a tangled pile of hula-hoops, strewn pantyhose, coat hangers, sewing machines and cotton candy installations, they all contribute to a cinematic environment. Each energetically charged object directs the performers in the crime scene. Floppy-flappy flesh suits, a homeless sex scene (or is it rape?) create esoteric distortions . A physical fight with battle ropes, a struggle for catharsis; a large scale canvas conceals a mountain, the stage is a living painting with no frame. Surveillance video is projected onto the wall with four screens portraying scenes from art gallery security cameras. This work reflects the art world itself; it is process on display. At once a horror movie and a lover’s tale—Fraggle-Rock-meets-Hitchcock-meets-Fellini-meets-Bouffon-meets-opera in a whodunit murder mystery on psychedelics, a rubber jungle, an exorcism, a meeting place between the baroque and the abject.

Inspired by I, Martin Short, Goes Home, Kiera Boult‘s Hamilton’s My Lady rebrands the once-coined “Ambitious City” in a mostly improvised stand-up-comedy-song-and-dance number through which she critiques local political and social issues. Kiki, aka the people’s princess, is the “celebrated black bi-racial (light skin) icon who navigates white institutions with ease,” joined by “leading scholar on Kikiology,” Dr. Double D Rosé (Delilah Rosier). With the same degree of “light-skinned hubris” as Martin Short, Kiki brings audiences into the oft stereotyped world of Steel City via a bold, political-ad-campaign-style video. With pomp and circumstance, Kiki educates her audience on Hamilton’s sites of failure (industrial emissions from a century’s worth of reliance on coal-fired technology), and botched tourist attractions (a sewage leak that once flowed into Chedoke Creek). With acerbic wit, Kiki compellingly argues that Hamilton’s steel and iron histories are being replaced by the not-for-profit-industrial-complex as the new face of Hamilton and sheds light on a number of call-out letters that emerged during COVID-19 lockdowns in local artist-run culture. The deluge of call-out letters seemed like a moment for opportunity within ARCs to change, but as Kiki astutely notes, nothing much came of it. Kiki’s prodding prompts me to think about Audre Lorde’s claim that we need “the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama.” [3] When the audience demands an encore, Kiki shouts, “just to be messy…what was your favourite cancel letter?” and the room goes silent.

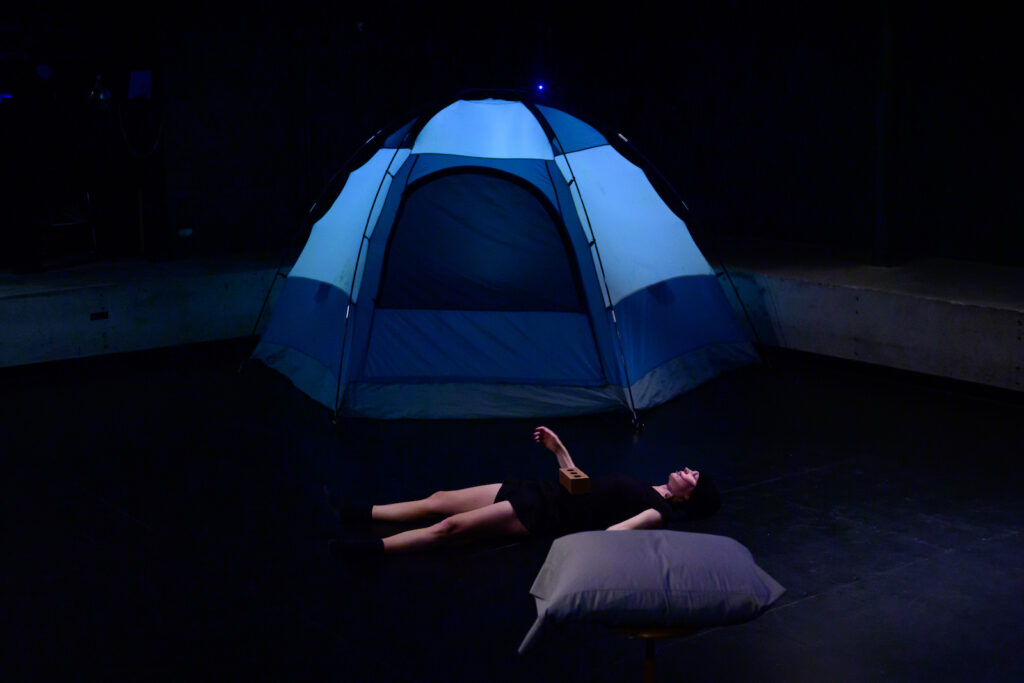

Cradling a pillow, Julie Lassonde gently welcomes spectators into the room creating an atmosphere of comfort. She welcomes us, “take your time.” My nervous system calms in her relaxing embrace. Light on her feet, she glides around the dimly lit room which holds a dimly lit tent, a mattress and a wooden table. I am settled by the ASMR-like quality of her voice and from the recorded sounds of night sky, quiet thunder, distant rain. On our terms explores the bounds of psychological safe spaces and, through text and movement, questions the conditions of accessing these. How does it feel to have no privacy, she wonders, after seeing a homeless woman pee outside in a privileged neighbourhood? She begins swinging a brick and despite the rational knowledge that she is in control of it, this action still generates an uneasy tension in the room. As she swings it in the direction of a young girl, I think about how Lassonde is the one in control, not us. Drawing on the importance of social collectivity, Lassonde earnestly reminds, “we don’t have to go with the flow.”

A baby screams behind the small audience that has gathered at Leslie Grove Park to watch one of three parts of Jackson 2bears and Janet Rogers‘ Medicine Shadow, which evokes spatial dimensions of storytelling and spiritual understandings of place, and complex remembering across time. 2bears explains how he used to spend time in this park with his father and fellow Indigenous artists and friends years ago. A blanket is carefully placed on the ground with other items—feathers, sprigs of cedar, a rattle and a red pouch of tobacco. Songs are offered by Rogers and the ceremony begins. 2bears begins digging up dirt from the ground, creating a small hole. He lays his whole body down, places his entire face inside the hole, and begins to sing. The smell of freshly churned earth is visceral and I feel the vibration of someone singing into the earth. After a while, he lifts his head slowly from the hole and has dirt on his face like a child. The vulnerability of his gestures churns something inside of me. He fills the hole with the tobacco and the crackle of cedar lit on fire is refreshing in the urban environment. Smoke spews from the ground. A tin filled with dirt from Treaty 7 lands (around Lethbridge, AB, where Jackson currently resides) is dumped into the smoking hole and the soil that was pulled up in Tkaronto replaces it. What imprints do we leave on the land? What does the ground carry? The performance reminds that land holds longer histories – that soil is a living, breathing entity. The smell of sweet grass lingers as I walk away from the park, the baby still crying.

In The Shop of Emptiness, Jusuf Hadžifejzović sells wrappings from items he has collected since his invitation to participate in the festival at an “art store” installation at OCAD University’s Ada Slaight Gallery. There, folks can pay up to fifty dollars for their own signed piece of trash. The remaining items from the shop later appear on stage at the Theatre Centre as part of The Glory of Emptiness. Dishevelled, the artist takes a pill, pokes himself with a diabetes reader (a private action made public), and proceeds to momentarily place a chair on his head, followed by a brown leather helmet with spikes. Volunteers tape empty packets onto his body, covering him. A cacophony of music, ranging from human rights agitprop, punk rock, and classical to a horn solo, gradually picks up in intensity as he becomes engulfed by the packets. Watching this older man scuffling around in sandals is endearing–tenderhearted; he possesses a childlike demeanour. Segueing between the absurd and the philosophical, the work reflects the arbitrary (and preposterous) nature of value, particularly as it operates within the world of art.

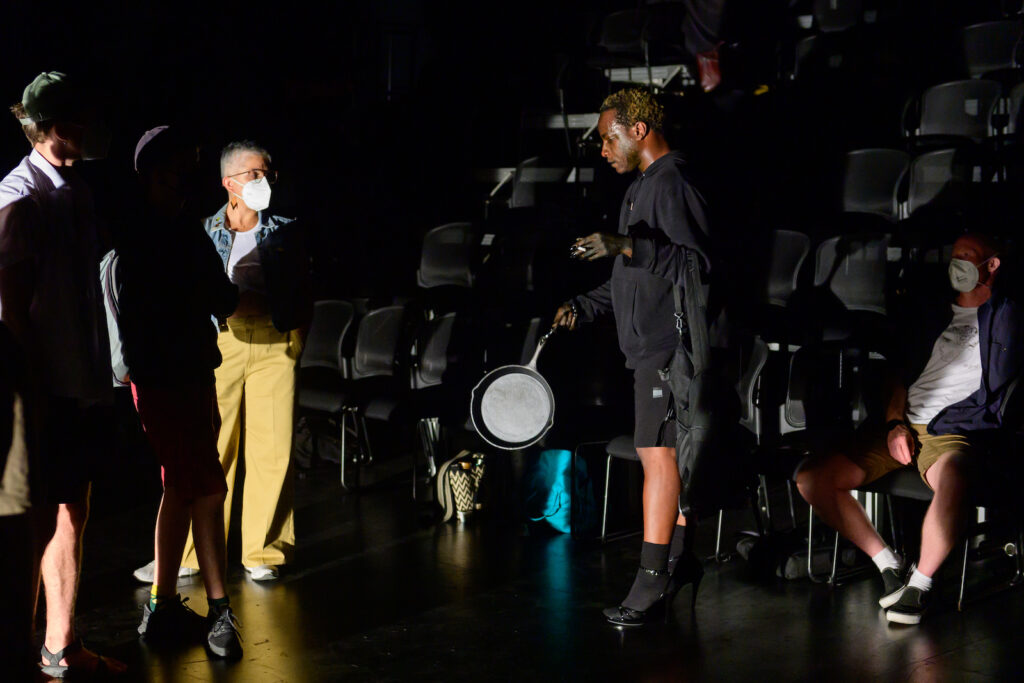

keyon gaskin establishes a certain intimacy early on in its not a thing by offering small cups of a mysterious blue bourbon elixir to audience members milling around the lobby before the performance. Guests are eventually invited into the theatre space by gaskin, cloaked in all black. Shortly after, the artist walks out, leaving the seated audience alone in the darkened theatre. About five minutes later (still in dark silence) we begin to hear gaskin muttering, clamouring, moving all around us. When he reappears, a single Leko light in the corner of the room is turned on and viewers are asked to leave their seats and come down to the floor. The blinding light blazes from a corner of the room and faint music pours out from headphones as gaskin moves through the space—coming up close to people’s faces, then sliding out to the periphery, imitating audience members’ stances; almost mocking at times, skittish at others. The clever use of shadows and light speaks to the politics of both the invisibility and hyper-visibility of Black bodies. Chaotically staggering around, gaskin chants No lives matter… There is no hope… It doesn’t get better… Lil Wayne’s 2011 track “She Will” starts to play from the loudspeakers and we are asked to reframe the lyrics, metaphorically applying “she” to mean the institution, the workers, immigrants, refugees, those doggedly trying to keep their kids fed and their bills paid:

Karma is a bitch, well just make sure that bitch is beautiful

Life on the edge, I’m dangling my feet

I tried to pay attention but attention paid me

[….]

She will, she will, she will

Maybe for the money and the power and the fame right now [4]

Black ink drips down his face like tears in the hot white light. He spits dice from his mouth into a cast iron frying pan reminding us that success is about chance, not pulling yourself up by the bootstraps. Self-reliance and hard work are not enough. gaskin’s use of stereotypical imagery (hoodie, backpack, stripper heels, handcuffs) brings forward racial tropes made visual by a climate of anti-Black violence. His high heels are replaced with tap shoes and like the ghost of a song-and-dance man, gaskin often disappears from view, flitting around to negate the gaze of a mostly white audience. He removes his pants and underwear and begins to tap dance, ass, thighs and cock glistening in the light. At the end we are asked not to clap, but to just leave.

Michelle Lacombe begins untying shoelaces of audience members whose feet are exposed and dangling over the seating area. Then, standing in the centre of the room, she unties her own thick, white, lengthy laces and proceeds to hold them up for all to see, making eye contact with viewers and slowly shaking her head NO. The laces are then methodically stuffed into her mouth until they are tightly (and barely) contained by her lips. Chewing… chewing… chewing…, the sinews of her jaw muscles flexing, working, a tension fills the room. She is breathing harder, body full of foreign objects. The corporeal discomfort is evocative. An intestinal panic, a climactic stress rises, and I begin to seriously wonder, is she really going to swallow them?

She stops the mastication process and slowly yet violently yanks each long lace from her mouth, through her teeth—a magical transformation has occurred—the laces are now black. She re-laces the white shoes with the now black laces, configuring an “N” pattern on one shoe, and the other in a square “O.” The shoes spell NO, which not everyone will notice—motioning toward a passive refusal. A celebration of minimal gestures, Lacombe’s work is self-contained, and nothing is left on site. The NO seeps outward into the world, on the fringe of visibility.

~ ~

Taken as a compositional whole, the aesthetic power of the festival can be found in its patchwork ability to mirror the collective moment we find ourselves in—there is no unifying narrative or defining structure, and these are indeed disorienting, indeterminate, and chaotic times. And so, not tamed by a central focus, but rather choreographed by intuitive and visceral frequencies—the curation allowed us to sit through these moments, attune to feelings, float between dreams, attend to thoughts and experience discomforts: to be present with ourselves and others. Following a very long time without being able to do this, that is a gift.

[1] Pechawis, Archer. “I Am Not Dead.” Other Places: Reflections on Media Art in Canada, edited by Deanna Bowen. Media Arts Network; Co-published with Public Books Toronto, 2019. otherplaces.mano-ramo.ca/archer-pechawis-i-am-not-dead/

[2] hooks, bell. “Eating the other: Desire and resistance.” Black Looks: Race and Representation, Boston: South End Press, 1992, pp. 21–39.

[3] Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of the Erotic.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde, Crossing P, 1984, pp. 53–60.

[4] Lil Wayne. Lyrics to “She Will.” Genius, 2022, genius.com/Lil-wayne-she-will-lyrics.