Sorry, you just had to be there! It’s something often said about performance art—that it’s fleeting, ephemeral, it leaves no traces behind. That the nuance of a performing body cannot be reproduced in other media—that something is lost when it is archived through the imperfect frames of photography, or video recording, or, in my case, language. “Performance’s only life is in the present,” Peggy Phelan explains emphatically, in the opening lines to her famous essay on the subject, “Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.”[1] Throughout her text, performance’s shift into the realm of documentation is always marked by loss: she explains that the performance critic can write “toward disappearance” rather than “toward preservation”[2] in order to acknowledge this material reality.

This past October, I was roaming around the 14th annual 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art having similar conversations. I was being introduced to participating artists and other beloved community members as the festival’s responding writer, and invariably, the conversation veered towards the challenge that lay ahead of me. That it’s a very intensive week! That there is so much to see! What if you miss something! I readily agreed: it can be hard to balance being “present” for the unique rhythms of performance as an audience member, while trying to hold details in one’s mind for posterity’s sake—to “collect” all the pertinent facts of an artist’s work before they inevitably transform under the hazy lens of hindsight. Before disappearance inevitably settles in. Watching performances across the entirety of that week, I wrote a quantity of notes that easily verged into “overkill” territory, sitting cross-legged on that concrete floor, acutely aware that each moment when my eyes were on my notebook was one that took me away from my surroundings, from the social fabric of the room, and from the performer who was commanding our collective attention.

This all sounds highly tortuous, but I assure you it wasn’t. Halfway through the week something shifted for me, a change in perspective that has only been cemented further as I reflect on the festival in hindsight: this pervasive assumption that performance art, as a genre, is defined by impermanence doesn’t account for all the things it does leave behind, everything that we, as an audience, are invited to share in its wake. We received a great deal throughout the week, and we gave something back in exchange. As a festival, 7a*11d is modeled around that sense of relational abundance, and in reflecting on the works by this year’s participating artists, I’m struck by how frequently they engaged with the possibilities—and significant challenges—of reciprocity. In coming to recognize this, my approach to festival note-taking shifted: from an uphill battle against forgetting to something more like a loose network of connections, a nonlinear map of shared affinities found between each individual work. The following text is designed to reflect that style of documentation—I’m not aiming to write towards disappearance or preservation, as Phelan might say, but rather, I’d like to use this essay to collect the moments (large or small) when these works grazed up against, challenged, or echoed one another; what those amorphous points of contact leave behind. I’m guided more by Rebecca Schneider’s prompt to reconsider the “singular” quality of a performance artist as a polyvocal one, a body reaching towards others in both the past and the future through accumulative citation and networked lines of influence: “Approach solo work rather more like a call and response. Take up antiphony as a model for reading.”[3]

But really, this realization clicked into place for me while watching artist Heidi Nagtegaal move through 7a*11d’s chit-chatting crowds at 630 Queen Street East, offering everyone a headband or bracelet from the endlessly fluffy bundle of yarn in their hands. Nightly, across the hours we spent together, these small markers of shared affinity would start to materialize on people’s foreheads and wrists—a signal of our shared commitment as an audience for performance. At Nagtegaal’s encouragement, I collected a new headband or bracelet each evening, and in the following days and weeks they have remained in my daily life like a surprising (and very welcome) residue of the festival. One is found knotted in the bottom of my backpack; one is tied to the handle of a tote bag I take to buy groceries; one dangles from the edge of a bookshelf near my desk as I write this. As a performance work, Headbands & Bracelets was subtle and modest in approach, but its scope was vast: mapping the relationships formed in this artist-run performance community, both as we gather together and as we disperse throughout the city (and beyond it) into the rhythms of our daily lives.

So, taking a cue from Nagtegaal’s connective threads, here are some other knotted, and decidedly nonlinear, relationships—written as calls (and responses)—that have remained with me since the festival last October:

EXCHANGE VALUE

From my notebook: cost is relative, cost is not always money—we know this. Across the festival, economies of exchange were modelled in different ways by the participating artists; all staged within the emptied-out environment that was 630 Queen East, a ground-floor condo retail space currently available for lease (perhaps, speaking cynically, Toronto’s purest form of value). In my memory, these ideas are anchored beautifully by Emma-Kate Guimond and Rue Jovanovic’s complex sequence of negotiations in Strong Legs Folding. Loonie coins and clear glass marbles are arranged on checkerboard floor panels like a schoolyard game. Guimond moves throughout the mottled-gray space, vocalizing a fractured series of reflections on relationships where value and intimacy are inextricable: conflicts with a lover, a landlord, a therapist—all sex and survival and affirmation under late-stage capitalism. (A floor panel is flipped over, revealing a banner that reads “OBLIGATION?” in a cursive script; Guimond repeats, “I owe him; I owe him; I owe him.”) Dressed in black, Jovanovic supports and echoes her movements—they are described as Guimond’s “witness, stagehand, and friend”—yet they also embody her mirror, her shadow, her structure: they guide each syllable of her narrative with the authoritative clink of two marbles in their fingers. As they move together throughout the space, the effect of Jovanovic’s presence on Guimond’s action is palpable: they stand like a negative space carved from the textures of everything she reaches for—that is, the space of debt and desire.

Elsewhere, more give and take: Tyler J. Sloane sits amidst the detritus of a night out in the staged approximation of their bedroom; trying—and failing—to ground themself through the choreographies of self-care and queer hookups as reconfigured through capitalism. “Face card, no cash or credit,” a Troye Sivan track plays as they dance. The chorus finishes: “Give me a call if you ever get desperate, I’ll be like one of your girls.”

An outstretched hand; an offering. My memory is reaching towards Daisuke Takeya’s masterfully funny Itadakimasu / Taking Lives, which closed out the festival. Standing at a raised table in a crisp white t-shirt, he solemnly begins slicing fresh salmon before assembling a small plate of nigiri and walking outside to offer passing Queen East vehicles a quick snack. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no one bites, and he returns indoors to share with the 7a*11d audience more slices of tuna and salmon from the soft flesh of his forearm. We are fed; we receive; we form our own economy—a grocery cart’s worth of supplies (fruit, cucumbers, salsa, cans of Coke, a bag of frozen veggies) are excavated from a monumental pile of dirt, one by one, treated by Takeya with equal reverence and distributed amongst the crowd. It’s delightful to watch the aesthetic trappings of so-called “serious” performance art—the dirt, the knives, the austere clothes, the neutral affect—be used to circulate these mundane items, to get us all prepared for dinner.

The value of a gift: Andrew James Paterson, one of 7a*11d’s Éminences Grises, concludes his performance of remembering and reticence by removing the two small paintings that flanked his character Pate and offering them to members the audience. On the one hand, it’s a cheeky gesture: absorbing the art world’s most consistently “valuable” investment (painting) into, arguably, its least commodifiable (performance). On the other, its remarkably touching: an offering in return, a redistribution of legacy as something that’s shared.

Next to a discarded pair of Blundstones and a pile of clothing, Tess Martens reclines with her arms draped above her head. She is nude, like countless women before her, posing for an audience. Her face is neutral as she shifts her body under the sharp red wash of an LED light, approximating the postures of models in Baroque painting. My Baroque Body is six hours in length. Some might say a performance of endurance; others might call it a shift at work. In many ways, both are true: Martens is enacting the slow, painstaking labour of being looked at, participating in an economy of presence and attention that has occupied women throughout centuries of European artmaking. She shifts her body and looks back. For an hour or two, she and I are mostly alone in this hollowed-out retail space. It feels too simple here to point to some rhetoric about the objectification of women under the male gaze—although, of course, that difficult truth is never far from reach—instead, I’m struggling to hold her steady eye contact. She adjusts her pose yet again. I continue to take notes. We are both doing our jobs.

Work is work: Tanya Mars, 7a*11d’s other Éminence Grise, distributes a survey amongst the audience members throughout the week of the festival, asking if we’re “Skeptically Optimistic” or “Optimistically Skeptical” about a range of circumstances, some irreverent and others quite transformative. Thanks to Mars’ playful phrasing, each one is a deceptively difficult choice, a negotiation between justifiable disappointment and lingering hope. Feeling the need to assert myself further, I draw a small heart next to: “Performance artists will unionize.”

SUPPORT STRUCTURES

“I am so glad you’re here, pass it on.” My notes from What We Crave, the expansive performance gathering organized by Jess Dobkin, Laurel Green, Joyce LeeAnn Joseph, and Shalon T. Webber-Heffernan, are scant, but my sense memories more than make up for it. There’s the soft feeling of red weaving between my fingers—the long individual strand of yarn that connected all the guests seated at the gathering’s long dining table, ornately decorated with fruit and flowers. There’s the sharp bite of ginger candy in my mouth—one of many small treats on my plate that we were guided in eating by each of our four dinner hosts—and the ambling conversation with my tablemates, about the challenges of teaching and the pleasures of freshly washed sheets. There’s the quickening in my lungs as we unfurled small paper streamers, jumping and dancing and screaming to Whitney Houston to conclude the event. Earlier in the evening, we were asked to write our individual cravings down on small sheets of paper. I no longer recall what I shared, but I do remember how that table facilitated “craving” as a collective practice, a sensation built through being attentive to one another. The core demand of Houston’s karaoke classic—“I wanna dance with somebody!”—was the ideal finale of What We Crave as a gathering: the clear sounding of a desire for intimacy, for shared support, for catharsis, for desiring itself.

More small bites: wandering through an installation of items that balances the surreal and the mundane, Anja Ibsch places a large beet in her mouth. Her expression implacable, she steps back and forth amidst floating balloons, dangling pantyhose, and small ornate tables, slowly piercing the deep purple vegetable with an endless supply of white-tipped sewing pins. The result is playful yet prickly—I can sense the frustrated accumulation of everything she might have said, every time she held her tongue.

Moving in a slow, deliberate line from right to left, I imagine Jessica Karuhanga dancing something like a sentence—that is, a declaration in another form of language. Much of this is spoken (or rather, danced) for her and her alone: she works with her back to the audience, and her gestures are frequently subtle, light twinkles of her fingers and small shifts in her ankles and shoulders. The quiet attunement of her work is remarkable to watch, as she steadily reaffirms the points of her body that push against (or are supported by) the structures of our shared environment: the topographies of her fingers and palms, the pads and arches of her feet—this is the grammar of her work. Titled You Feel Me?, the performance plays on the dual nature of that verb: connoting inter-subjective empathy and understanding on the one hand, and literal sensation on the other. (I am felt.) In introducing the work, Karuhanga quotes from scholar Uri McMillan, describing the work of Black women performance artists who engage in strategic self-objectification, rendering themselves as pliable matter in order to further explore the structural limits and radical possibilities of their racialized embodiments.[4] Karuhanga’s own pliability here—her body as language, as material, as structure of support—turns inward with each small gesture. She says a great deal without speaking at all.

Another point of contact: as Tess Martens shifts her nude body in different poses, the satiny luxury of the reclining seat that supports her begins to break down. She stands up and adjusts it: turns out, it’s a flimsy plastic patio chair, a cheap structure that comically fails to match up with the sheer endurance of her labour as a muse, an object. Eventually it is tossed aside with the pile of her discarded clothing, easily within view of her ongoing performance, and a replacement is sourced from a nearby closet; the uncomfortable, mundane reality behind the rapturous fantasies of Baroque painting.

For the first portion of Transference, Vanessa Godden isn’t visible to their audience. They had entered a giant plastic drum—filled at the base with a few inches of water—from a small ladder installed behind the shape. But their presence is palpable—we can hear the dull sloshing of water at their feet, see darkened shadows of their movement behind the opaque white material. Then, slowly, their fingers grip the drum’s curved edge and we witness their careful, deliberate effort as they find ways to fit their body into a series of successively smaller vessels filled with water: among them a metal garbage can, a plastic bucket, a stove pot, a glass jar, and lastly, a tiny silver bowl, barely wide enough for the tip of their elbow. With each new vessel, the water that Godden’s body displaces is splashed onto the floor, further soaking their bright patchwork clothing. Even weeks after the fact, I feel gripped by this performance in a way that’s difficult to describe. Through simple means, Transference beautifully embodies the difficult negotiations of a diaspora—referencing Godden’s own Indo-Caribbean lineage—between geographic distance and lived connection, cultural scarcity and relational abundance. Regardless of scale, Godden is always, always, connected to water.

A costume of a bruise: I write down this beautiful line, spoken during Emma-Kate Guimond and Rue Jovanovic’s sprawling performance of owing and yearning and refusing—it colours my attention. As if to signal a new chapter of Strong Legs Folding, Jovanovic slowly removes Guimond’s long rust-red dress and covers her in a new top and jeans as she lays passive on the floor. Jovanovic dresses her inert frame, holding her face between their hands as they pull a shirt down past her neck. The displacement of agency, the reluctant need to continue, the mundane intimacy of support—it’s remarkably moving.

And one more, behind the scenes: it feels important to acknowledge 7a*11d’s documentation team here, a support structure that’s essential to the festival. Henry Chan is something of a legend in Toronto, documenting performance art in the city for 17 years. The photos that accompany this report were all produced by him. Alan Peng and Jeff Zhao—of the Peppercorn Imagine production studio—provide video documentation of the festival and its accompanying artist talks. Why is it that academic debates about performance and its documented permutations rarely acknowledge the skilled labour of that very documentation?

LEFT WANTING

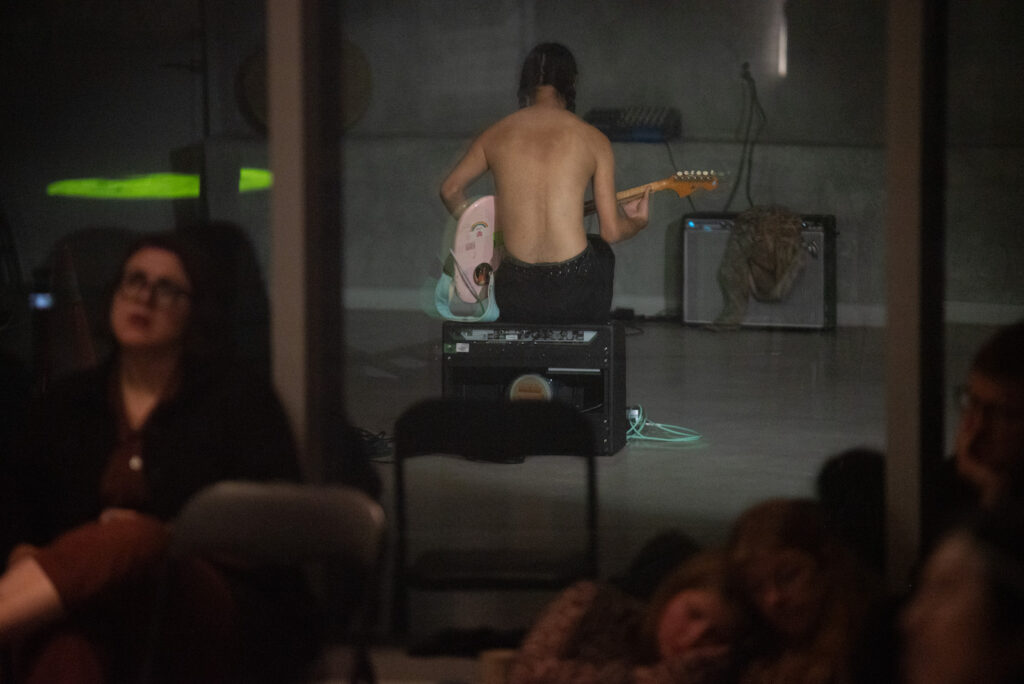

From my notes: to name something isn’t necessarily to know it.Having moved in a slow circle wearing traditional Prairie Chicken dance bells on their ankles, placed just above a well-worn pair of Converse high-tops, seth cardinal dodginghorse sits on an amp, their back turned to their audience. They begin playing low, wavering chords on a guitar, facing another amp some fifteen feet away. dirt song (calling to yesterday, today, and tomorrow) is an uneasy duet: the other sound source is playing an archival recording featuring the reedy British voice of Father Francis Cole Cornish, the Indian Agent assigned by the colonial state to govern Tsuut’ina land in the nineteenth century. As Cornish speaks haughtily and paternalistically about the struggles of cardinal dodginghorse’s ancestors—as if his so-called “expertise” supplants their lived experience and intergenerational knowledge—the guitar chords and reverberations grow louder and louder. Gradually, cardinal dodginghorse pushes their amplifier closer to Cornish’s voice, until the gap closes and the two sound sources are touching, face to face. In fact, “duet” feels incorrect here—there is no negotiation, no equitable exchange between voices. Cornish and the system he represents established this imbalance centuries ago. cardinal dodginghorse doesn’t use sound to expose a colonial voice—through their understated and complex performance, they work to neutralize it.

An echo: Jessica Karuhanga moves across the floor with her back to the audience, something like a mode of refusal. Yet throughout her short performance, she faces the large exterior windows of this street-level retail space—they act like mirrors given the darkened street and internal lighting. Over her own shoulder, we see her face reflected back at us. In this oblique way, we make contact.

Tyler J. Sloane sits in an approximation of their bedroom, slowly removing layers of drag and a full face of makeup. While I won’t come begins with an exuberant dance number, complete with rhinestone heels and a white fur coat, the majority of their performance occurs in this hazy after-state: the twilight hours after a club night, sitting amidst the lingering detritus of a party outfit, wondering if a certain someone might text. As their voice speaks in a pre-recorded monologue, Sloane moves along with a series of personal reflections on addiction and the broken promises of commercialized forms of “self-care.” Accompanied with multiple songs, their narrative creates a contrast, interestingly, between how performance can either approximate or embody desire as a sensation. They visualize the experience of addiction by reaching emphatically for some lines of coke on a mirrored surface, a gesture that works to literalize (and perhaps flatten) what is undoubtedly a nuanced internal landscape of embodied need as Sloane has experienced it. Is reaching for a (staged, artificial) object of desire necessary, in communicating these narratives to an audience? How else do we access their need, their grief, their anxiety, their yearning, through the choreographies of their body, the sensations it creates in this environment? Sloane concludes I won’t come by shifting from fake drugs to real medicine: leading audience members outside for a smudging ceremony, a reminder that the complexity of relational presence carries a powerful impact.

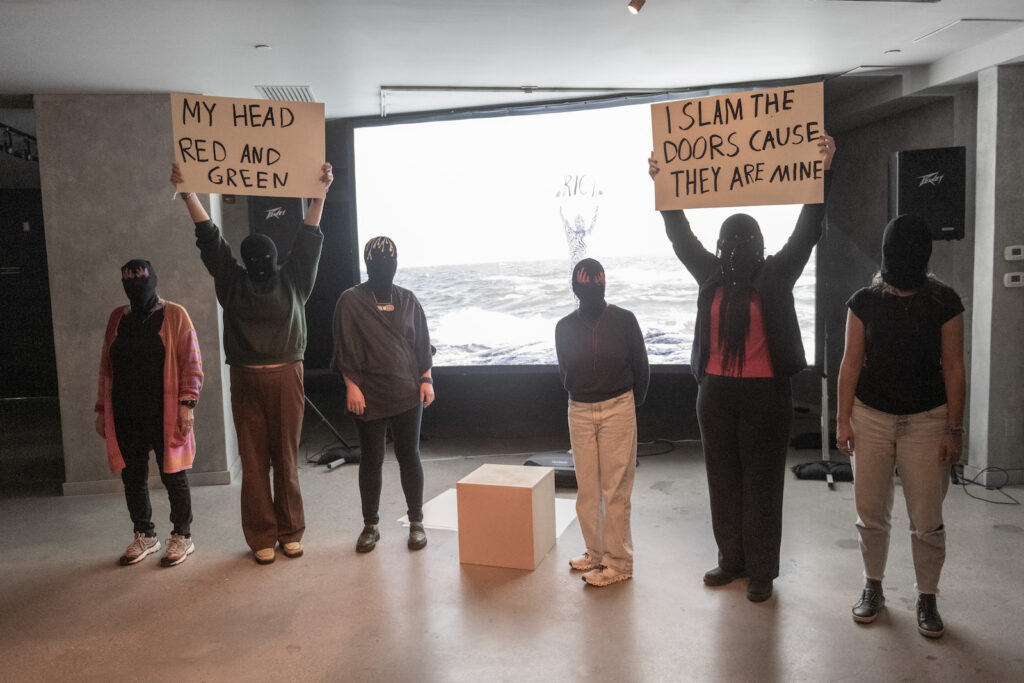

Follow the leader: in the LILITH ARTIST DUO’s surreal performance space, our guardian-host (a mask-clad young girl) prompts our engagement with a series of blocky, hand-written signs. SAY AAAAAH! and CLAP YOUR HANDS, some say. BREATH IN AND BREATH OUT. We follow suit. A few of her signs seem to communicate a fraught emotional landscape, one that’s ambiguous but nonetheless declarative. I SLAM THE DOORS CAUSE THEY ARE MINE, one says. My favourite, one that’s lined with an anxiety that feels personally familiar: AS SOON AS I GET A FEELING I DIE.

MUSCLE MEMORY

In Samuel Beckett’s one-act play, Krapp’s Last Tape (1958), an elderly man sits alone and listens to recordings he made earlier in life, reflecting on his younger days. At one point in the short play—which is either a monologue or a dialogue, depending on how you look at it—he skims, impatient, through recorded episodes of his life at 39, giving the audience quick and inconclusive fragments of who he had once been. Andrew James Paterson’s Pate’s Salt Carp makes excellent use of the artist’s distinctive sense of humour and his deeply citational approach: the title functions as an anagram of “Tape’s Last Crap,” itself a winking twist on the famed Beckett play. Clad in an orange shirt featuring the name of his character, Paterson (or Pate) sits before his audience and endeavours to crack open the black plastic of a VHS cassette, unspooling the shiny magnetic tape into a red mixing bowl. His table features a black gingham tablecloth, paper plates, a box of salt—he is getting ready for a meal. As he wedges a butterknife into the seams of the tape, he recites a restrained catalogue of dates, each designated with a declarative no or the occasional, resounding yes. Like Krapp skimming abruptly through his reels, we are provided little context for the meanings behind Pate’s vocalized calendar, but as an audience member, I can’t help but read deeply into each deliberate inflection. Some of his nos feel hesitant, a question lingering in the air, while others are firm, playful, angry. Like the simplicity of his “meal” (tape-noodles and salt), the relative austerity of Pate’s archiving only further emphasizes the richness of experience found just beyond the constraints of format.

Safe-keeping: in their Performance Art Daily talk, seth cardinal dodginghorse speaks against the desire for unencumbered access to information as a colonial framework. For Tsuut’ina and other Indigenous peoples, the strategic withholding of knowledge is an essential tactic for perseverance: “With our culture, you can’t know everything,” they explain. “That’s ok. Not all of our knowledge is accessible at any point in time. It’s a good way to keep knowledge safe, and that’s a big part of why a lot of our cultures survived.”

“Do you remember the grapes from last time?” From my notes, I don’t recall Anja Ibsch speaking much during #still, her sustained performative investigation with a series of objects, which she has elsewhere described as “thinking with the cells.” Yet she asks her audience this oblique question, filling a leg of beige nylon pantyhose with red grapes before stretching the material over her head and crushing the fruit slowly against her face using a small pane of glass in an ornate brown frame. Much of #still sees the artist moving through an installation of delicately arranged objects: wooden tables and clear balloons, small cartoonish bunnies, paper cutouts of bone clusters and figures from art history. I am struck by Ibsch’s use of her own body in #still as she engages with her varied objects—she is at once a hard edge, an open vector for sensation, a destructive and curious force. She deliberately shaves down an oval of soap, using a cheese grater placed between her legs. The room fills with the powdery, precious smell—a fascinating contrast with the slow violence of her gesture.

From within: Juma Pariri flips over, entirely naked, resting on their shoulders and neck, their hips high in the air. Carefully, they retrieve small bundles from inside themself: small pieces of clay, each wrapped in the protective layer of a condom, stored inside their body. As we watch them work, I begin to imagine their upside-down posture like a horizon line, a rich layer of soil, an invitation for growth.

SOCIAL FABRICS

As LILITH ARTIST DUO (Elin Lundgren and Petter Pettersson)leads audience members into their performance space, we are each asked to wear a black balaclava-like hood, with tiny holes cut for eyes, mouth, and (in some cases, helpfully) the arms of our glasses. The transformation feels immediate: the people I was chit-chatting with mere seconds ago, waiting in line to enter the space, are suddenly foreign to me in this changed environment, all typical facial markers of identity lost. I find myself submitting willingly—and gratefully—to the machinations of our 11-year-old host, as she diligently arranges us in a wide circle. Audience members are solemnly led to the front of the space in different arrangements, given hand-written placards that feel halfway between an actor’s line prompts and protest signage. This ambiguity between a theatrical setting and a political demonstration feels apt to emphasize here, and it’s one that leaves me somewhat destabilized. The performance ends with our young host atop a low plinth, her upraised sign reading RIOT. We stand politely as the low beats of the ambient soundtrack continue to hum and warble. Up until now, we had been following her written instructions diligently, yet here, as an audience, we are frozen in place. What is being asked of us in this moment? What does this word mean, when it’s emptied of all urgency, direction, demand? As we file slowly out of the space again, where does this leave us?

We are asking: as a prompt to participate in What We Crave, we submit a short note of our cravings in a google form. At the beginning of the gathering, our wonderful hosts Jess Dobkin, Laurel Green, Joyce LeeAnn Joseph, and Shalon T. Webber-Heffernan, seated at the four cardinal points of our long dining table, read our submitted cravings aloud in a polyvocal blur. The cravings are mostly cacophonous layers of dreams and demands: personal, universal, mundane, expansive. But slowly some begin to echo, repeat, gain accumulative and collective strength: ceasefire ceasefire free Palestine free Palestine free Palestine.)

Juma Pariri’s performance begins with a screening of their short film, Pe ataju jumali / Hot Air, made in collaboration with a range of Indigenous peoples across South America, working primarily with the Sikuani people of so-called Colombia (Pariri themself is from the Kariri people of so-called Brazil). The sci-fi narrative follows a collective of seed sowers using what Pariri calls performagic activation to disrupt the petro-capitalist colonial state, which has (quite literally) poisoned the air through predatory resource extraction. The sowers move through urban centres, carrying breath and seeds from the forests of their home communities, directly targeting the infrastructures of climate crisis (such as gas stations) and capitalism’s broken promises (all that hot air) to bombastic and transformative results. Pariri’s presence in Toronto could be understood as another such activation by a seed sower, as they carry clay from their body to a small effigy of a petro-capitalist man, and prompt us as an audience to dismantle him, piece by piece. “Turn him into something organic,” they instruct us, “his body will be useful.” Softened in my fingers, a small piece of this clay body is carried in my pocket back out into the city. I press it into a brick façade as I wait for the streetcar, along with the wish that our city might listen.

Another offering: with an outstretched arm, Daisuke Takeya distributes slices of fresh tuna and salmon to the crowd. We eat it readily, peeling each morsel from his skin. Along with the well-staged humour of his performance comes a vulnerable truth, one that many performance artists know all too well: to perform is to give yourself over to an audience, piece by piece. Perhaps our role then, as that very audience, is to give some part of ourselves back.

“What do you got?” “How hot is hot!” In what was described as a pep rally meets TED talk, Tanya Mars jumps in front of her audience in high pigtails, a knee brace, and a purple-and-gold cheerleading outfit. She’s ready to present the results of the survey she’s been conducting all week long, collecting data about our skeptical optimism and optimistic skepticism on a range of speculations about the future. Cheers or Tears for Humanity is uproarious, engaging, sarcastic, ambiguous—in short, it’s wonderful. Mars quickly gets us clapping, screaming, and waving glittery pom-poms as she does a cheer routine amongst the flames of a dying planet. The results of her survey on our hopes for the future (which featured assertions like “We will solve the climate crisis”; “The Rich will pay”; and “Astrologers will replace judges”) are shared with the crowd, interspersed with guided chants on energy use (“Amps! Watts! Volts!”) and global catastrophe. (“Our world goes tick tick tick tick boom, dynamite!”) Like the deceptive simplicity of her survey—which exposes how deeply interconnected these feelings of hope and cynicism can be when thinking about the future, the sing-along quality of Mars’ performance is highly infectious despite its serious content. It leaves us, the laughing and cheering crowd, a bit more bonded to each other as a result. What I take from Mars is that we ultimately need both—skeptical optimism, optimistic skepticism—in order to survive this present; in order to move forward together into whatever comes next.

The measure of distance: as Vanessa Godden moves their body into successively smaller vessels, water is displaced onto the floor in wide splashes. I imagine the long generational trajectories of their family in diaspora, as a person of Indo-Caribbean descent—of separation across oceans. Yet as their performance embodies, to stand within a body of water in Toronto means, on some infinitesimal level, to impact the levels of the coastline in Trinidad and Tobago. An impossibly tiny marker of connection, but one that moves me more than words can say.

Just one more, a welcome rhythm: could I even cover 7a*11d without mentioning Archer Pechawis? While not a billed performer in this year’s festival, Pechawis’ voice was nonetheless present, and I am grateful for it. He collaborated with both Juma Pariri and seth cardinal dodginghorse, singing and drumming to conclude their respective performance works. A different kind of call and response, a connective line drawn through the festival across different Indigenous nations and communities of artists. As he said about Pariri at their shared Performance Art Daily talk—which also featured the wonderful Theo Jean Cuthand—he knows another troublemaker when he sees one.

…

During one of 7a*11d’s nightly introductory remarks, artist and Toronto Performance Art Collective member James Knott said something along the lines of: “a good performance artist will always commit to the fucking bit.” I hastened to write this down, and their words got me thinking about commitment as an act—as it relates to the experience of 7a*11d as a festival, and as it relates to performance art more broadly. It feels true that performance, as a practice, is all about using your body to affirm your commitments in public: whether those be to a particular audience, a community, a legacy, an aesthetic, or even just to yourself. But as a festival, 7a*11d models relational commitment on multiple levels: even as an organizing principle, individual members of the collective work directly with individual participating artists—ensuring a dispersed and decidedly intimate commitment to collaboration between each performer and festival curator.

And perhaps that’s been my role as well—as an audience member, as a participating writer. Attention is one kind of commitment; translating memory into language is another. Neither is perfect, neutral, or permanent—but then again, no commitment ever is. Like Nagtegaal’s headbands and bracelets, the ways we show up for each other are always temporary, transforming, and are reaffirmed when we gather again the next night, and the night after that. As an audience, as artists, as a festival community, we continue to commit: we come back, we give attention, we call and we respond. In writing this text, if nothing else, that is the choice I continue to make.

[1] Peggy Phelan, “The ontology of performance: representation without reproduction,” in Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge, 1993): 146.

[2] Phelan, 148.

[3] Rebecca Schneider, “Solo Solo Solo,” in After Criticism: New Responses to Art and Performance, edited by Gavin Butt (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2005): 37.

[4] See Uri McMillan, Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance (New York: NYU Press, 2015).