By Natalie Loveless

Some music plays, a lovely smooth Latin something. There is a pedestal with a fishbowl on it and a small table with what looks like 24 bottles of champagne. Pancho López is introduced by festival co-organizer Tanya Mars. She informs us that López, who had been scheduled to perform last week but was denied access to the country, was finally granted a visa and would tonight be performing a piece called Anger. With that introduction done, López slowly lays out 8 pieces of paper, each bearing the word “VISA” in large font and all caps. When each sheet is in place—forming a barrier between him and the audience—he puts on an apron, takes out four vinyl letters—V, I, S, A—and glues them to it.

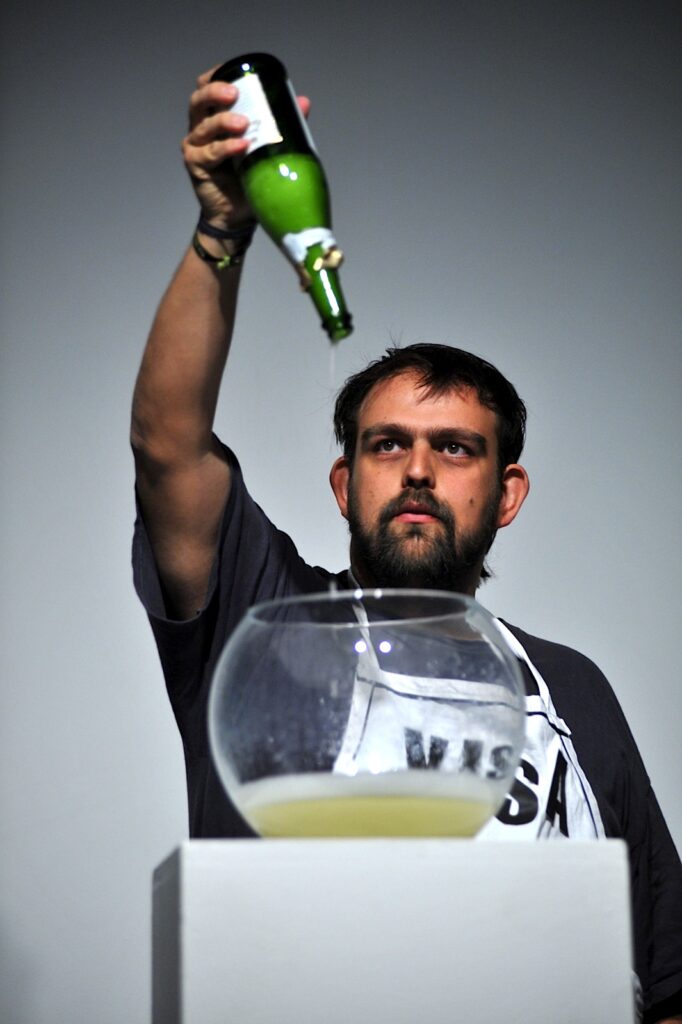

López pops a bottle to the music. The cork hits an audience member. He pours a small glass and hands it to another audience member. He pours a few more, with flourish, until the first bottle is empty. The next bottle he allows to pop safely, anti-climatically (all of us prepared, with ducked heads), and pours the whole bottle into the fishbowl. He repeats the process with the next bottle, and the next, sometimes shaking the bottle to the music. A dance of champagne, music, and foam. At one point the “S” on his apron begins to come up. He opens a glue stick and re-sticks the letter. He then takes out some chapstick and puts it on his lips—a visual rhyme. But mostly his action is repetitive: Pop. Pour. Pop. Pour. The only variation lies in his little dance with the bottle and the varying level of threat that he plays with as he pops each cork into or just above the audience’s heads. The performance is also punctuated by audience commentary: someone with a glass tries to signal for more champagne, another complains as a cork hits her, another finds a cork and throws it back at López. López plays with our expectations, while filling slowly, bottle by bottle, the large round fishbowl to the brim.

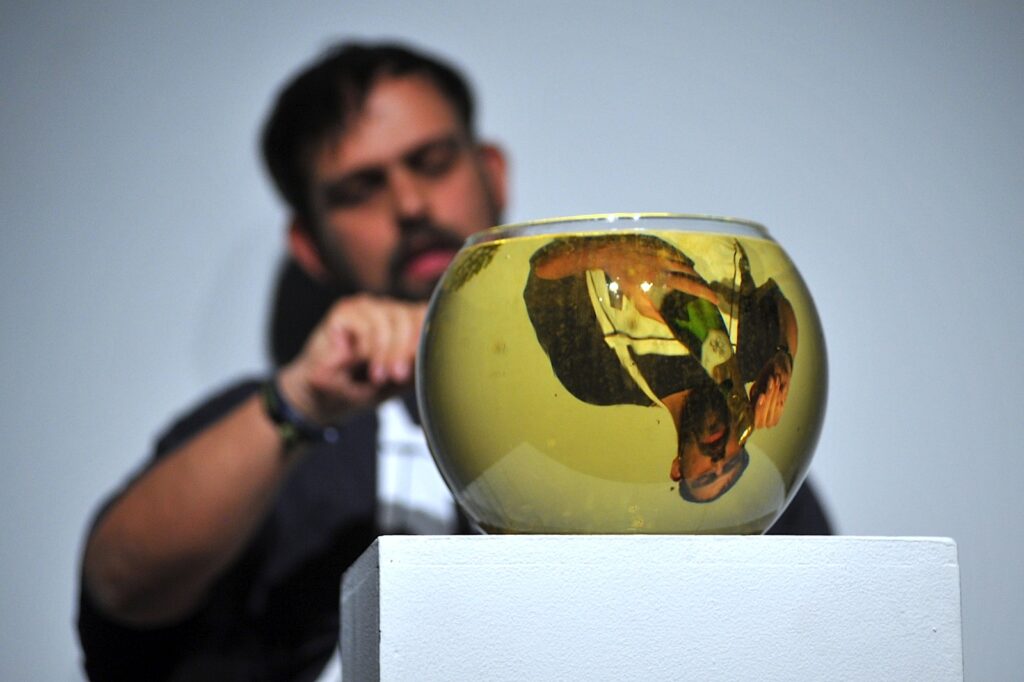

While pouring the bottles López gets more and more attentive to cleanliness, asking for a mop and wiping up any spills. As he does this we can see his image, inverted in the fishbowl, glowing golden with champagne. At bottle twenty-two the bowl is almost full, and I start to wonder how this will end: will he pass out more champagne to us, the audience? Will the bowl overflow? I am struck by the excess, waste and luxury that I’m witnessing. As the last bottle is shaken, popped and poured, we watch, breath held. It almost fits, sloshing just slightly over the brim. Bowl filled, López rips the letters from his chest—V… I… S… A—and places them in the bowl one by one. They float on top. He takes one sip from the bowl, steps back, grabs a red baseball bat and hits the bowl with all his might

It shatters.

Champagne splashes and runs across the gallery floor, its rich odour filling the air as the audience scrambles back a little, and the gallery staff come in to prepare for the next performance.