By Alison Cooley

I can hear a whip. I’m unsure if it’s against the floor, or against a body, but I hear guttural reactions to it from outside the studio.

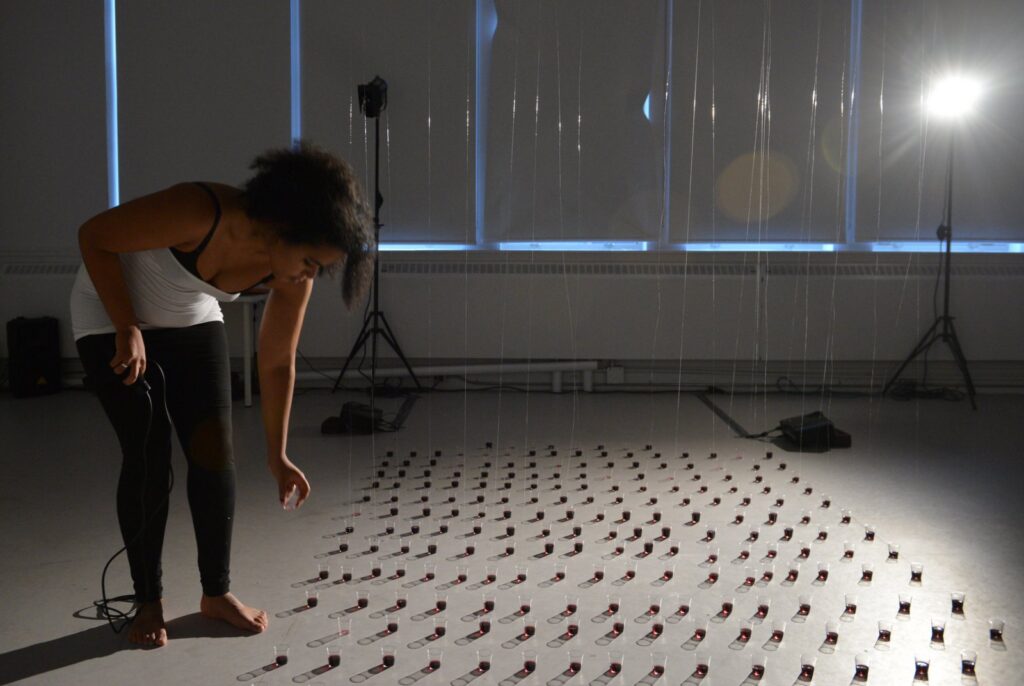

When I first enter Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro’s durational performance, it is her gaze, not the whip (which is actually a jump rope) that strikes me. Maintaining her direct and unwavering stare, Bikoro is skipping rope. Along the floor, she has laid out shot glasses of red wine in perfect rows. She spends the next three hours walking carefully between the lines of this grid, drinking, skipping, spitting, spilling, and humming. As Bikoro moves about the space, enduring the bodily tolls of drunkenness and over-exertion, she stumbles, brings herself to the ground, crawling instead around the array of shot glasses. As she skips her white tube top slips down, revealing a black bra underneath. The shirt has soon accrued a deep purplish stain across its front, like an amorphous liquid bruise.

Sometimes, Bikoro opts not to ingest the wine. Instead, she crunches on the clear plastic of the glasses, or runs them against the floor in slow, ever quickening, circular motions. The grind of plastic on linoleum produces the moving-too-fast rushing sound of wind in open spaces. Projections on two opposite walls behind Bikoro’s performance begin to play a series of clips of African artworks. I later learn they all come from Les statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die), a 1953 anti-colonial film which examined the impacts of European collecting of African art and the commercialization of African identity. Even without prior knowledge of the film, it’s clear the clips demonstrate the kind of cultural genocide the museum has inflicted on African culture: footage from inside a museum vitrine catalogues the gaze of white visitors, slow scans of masks and figurines fill the frame, clips presenting White missionary work and scenes of contemporary Black African life are interspersed among these move removed museum views. Jazz plays. There are unbalanced moments of levity in the music as Bikoro’s attempts to skip grow more failing, and she trips over the rope dangling among her legs as she walks.

I notice there are thin pieces of fishing line that run from the middle row of shot glasses, over a pipe on the ceiling, and are taped, finally, to the chalkboard at the front of the room. It’s unsettling because I have been sitting just beneath these strings, unaware that they anchor some as-yet-unknown-to-me gesture. There is tension in the air above me.

Nearing the end of her performance, Bikoro slides herself into a chair in the corner of the room, and picks up two objects which had hitherto been facing into the performance space like airhorns. I see now they are electric breast pumps. Bikoro slides her tube top down and unclips her nursing bra, suctioning the funnels to each of her breasts. Soon, she begins to produce milk. The music accompanying the projections halts for a moment and all we can hear throughout the space is the rhythmic sucking of the device. Once Bikoro has two full bottles of breast milk, she fills the centre row of shot glasses (some of which still contain the dregs of her wine). She hums along with the music, and once it stops, she persists. Her humming fills the room, as she removes the collection of fishing line pulleys from the board, and tugs on them. The glasses lift upwards. Some tumble over the top of the pole. She lets them slip. Starts to pull again. The glasses drift upwards. Bikoro’s humming continues as the glasses uneven themselves. She pulls and releases, pulls and releases. Continues humming, passes the lines to a bystander, and leaves.

Bikoro’s performance is difficult to watch, and like so many at the festival, operates in a shady territory of performative harm to the body. But it also raises questions of intervention and trust that revolve specifically around the Black body. While we may not recognize or be triggered by the danger of Liu Wei’s fishhook or John Court’s mouth-led construction, we have existing frameworks for alcohol consumption, and some of those frameworks are racialized. And as an audience, we are forced to ask ourselves how much we trust Bikoro’s endangerment of her body, with colonial violences playing as a (literal) backdrop.

But Bikoro says her performance is about love, and I have come to believe that in her gestures. Bikoro’s love opens up in the tender spaces of trust, respect, care. It’s in the things that are timeless— the lactation that bestrides the boundaries of biology and culture. It’s in the humming, it’s in the milk, it’s in her will to urge her body forward.