By Jenn Snider

Éminence Grise

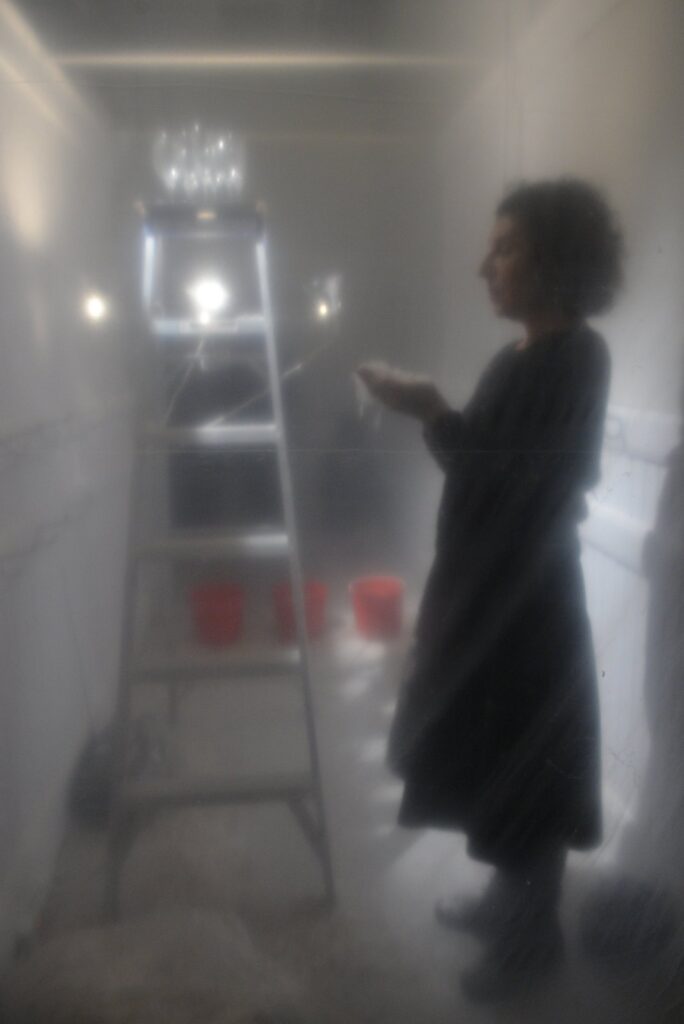

Pulling back the grey curtain I step into the viewing area and find I am just a few feet away from her. Tucked into a small closet separated from the festival crowds, Berenicci Hershorn’s performing space is articulated by gauzy walls of plastic sheeting and the effect defocuses her from our direct gaze. Everything is cast in a haze; the light, the sounds, and her movements. Hershorn’s performance will last for three hours, so it is fitting that I find her gazing at a clock. With heavy lidded eyes and a serene expression, her body slightly swaying, in her hands are loose white feathers and down that one by one fly from her palms on an unidentified breeze. She holds them out as a dreamy offering, and the scene is as something surreal. Part reno, part domestic nest, the materiality speaks imprecisely and the air is ambiently feathered. Hershorn’s stillness is active, and it gives the sense that this tableau is about to tell us a half-forgotten story. When her body finally does move, it’s as rhythmic as the second hand, cyclical and methodical and unlikely to pause.

Berenicci is a 2014 7a*11d festival Éminences Grise. Over a period spanning more than 40 years, she has been producing unique solo and collaborative site-specific art. Her work incorporates performance, video, sound, sculpture, installation, and public art presentation. On the first night of the fest we cheered as she was presented an award by Clive Robertson (her co-honouree) as part of his performance. On day two of the festival we had the chance to hear from Hershorn about her artistic origins and practices in manifesting intention (see my post titled “Metonymic Intentions: Language sound body (Performance Art Daily).” Tonight, we have the chance to experience Hershorn’s latest performance, entitled To Be And….

The sequence of her movements is as follows:

She stands with hands full of feathers until they all blow away; she climbs the ladder to rattle a tray of delicate stemmed glassware perched at the top; back down on the ground she holds a red bucket and dips her hand in to grab handfuls of salt which she sprinkles on the floor as though seeding a field; she washes her hands and forearms in another red bucket of white powder and then plunges her hands into a third bucket filled with feathers; lightly grasping two handfuls, she returns to the clock. Repeat.

In speaking with Hershorn by email in the days after her performance, she tells me that there are many inspirations that resulted in the final image of her piece, which is a meditation on where the mind goes when it’s between life and death, and on the malleability of time itself. Of the sources that spurred her creative imagination to develop this particular work the strongest was an old photo she found of a man being slowly tortured to death in the middle of a public marketplace while everyone went about their business. In hindsight the positioning of Hershorn’s performance next to the busy festival bar, in light of the acknowledgment of this image, has a parallel that can’t help but be suggestive.

I sit on the floor and try and be with Hershorn for a little while. She’s in her own world, so the togetherness is proxemic only. In the rare moments when the adjacent bar is quiet, I can hear a low eerie rumble that I can’t identify as anything other than the sound of an ethereal distance. The plastic sheeting that encloses her space from both sides of the long closet has the effect of a sense suppressor. We’re probably just shapes of blurry incoherence to Hershorn. To us she’s a dark figure of focus, meditation, and spellbinding methodicality.