By Alison Cooley

The still life has been sitting there all day. Arranged on a table by the studio’s back wall, an array of fruits and vegetables across a fur tablecloth have caught chance glimpses from an audience huddled around a speaker broadcasting claude wittmann’s radio performance. It is the nature of so many bodies in so little space together that some element of a later performance inserts itself into the daily operations of the early day, but for Marisa Hoicka’s Nature Morte the scene seems appropriately, obscenely tempting. When we finally sit, I fixate on the cabbages, melons, artichoke hearts, the wilting stems of the clementines, the teal and the fecal brown tones of a canvas hung behind the scene.

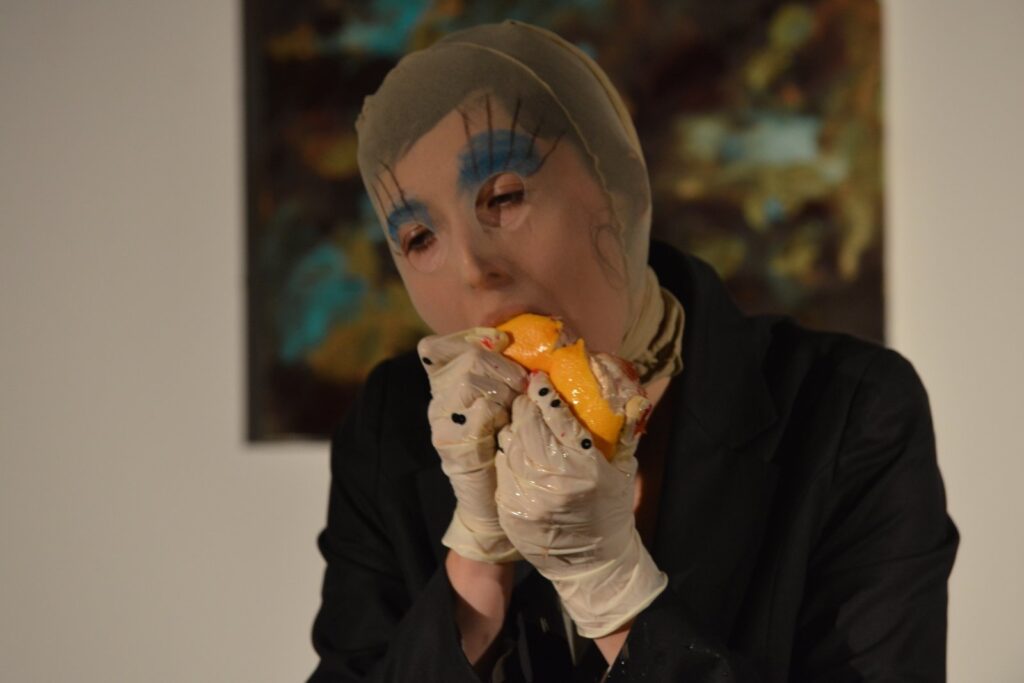

Hoicka enters her performance in a black blazer and leggings—an awkward, low-budget kind of service staff uniform (think artists who spend their days working for catering companies). She distributes orange slices from a tray amongst the audience. We catch her horrible eyes, through holes in the nylons over her face. Eyes within eye, small and darting, framed by gawdy eyehole makeup drawn across the upper half of the face.

Hoicka’s persona is hospitable and curious, alien and childlike, beginning a sensorial exploration of the table by pouring a jug of milk into a pyrex bowl. Soon, she is slowly clawing open grapes with her latex-clad fingers (the nails of which are painted red). She carefully examines the fruits’ innards, sometimes opening them towards her audience, revealing juicy dripping membranes. Inside a few choice elements of the scene, the host discovers foreign elements: black sequins spill from a grapefruit, she pries latex gloves from inside an orange, and climbing onto the table (an act which sets a series of shaking foods in motion), the host echoes a kind of magic act, unwinding a long black spool of yarn from inside an eggplant.

Hoicka blends the animated fakery of unconsumable foods with curiosty and natural wonder. In her gestures to the tradition of still life, she makes these excessive delicacies newly strange, absorbing them in a comedic and anxious overstimulation of the senses. When the uncanny host makes a first attempt at consuming a grapefruit through her masked nylon mouth, it manifests a visceral failure of consumption. The European still life tradition, which Hoicka draws from in her ornate setup, marks an overabundance of wealth, gloats over the spoils of hunting or harvest or collecting, glistens temptingly as it catalogues a bounty. It resignifies food, first and foremost, for visual consumption. Evacuating a vegetable of its alimentary purpose and of the labour of its cultivators, the still life tradition insists on food as status.

Hoicka’s performance ends with a flourish. Cracking open an eggplant, the host throws a handful of black plastic feathers into the crowd. She bows and pops a solitary grape into her mouth. The perfectly extravagant scene Hoicka assembled for her audience’s visual consumption has descended into chaos. Amidst scattered evidence of the messy reality of eating, our host finishes with the aristocratic pretense of control.