By Michelle Lacombe

What Does it Mean to Forget?

Despite the countless talks and panels addressing the relationship between performance art and the museum I have attended, as I sit in the Art Gallery of Ontario to watch Louise Liliefeldt perform, I realize that this is actually the first time I have seen contemporary performance art in a major institution. This context has a serious impact on my experience so I will digress a bit.

Even in the best of conditions, I have a somewhat hostile relationship to the museum and generally don’t think it is the place for performance art. I’ll admit that this opinion is ideological, a gross generalization and, at that, one that says more about me than the institution. Clearly, the museum can be a site, a context, like any other. But I doubt it.

So, as soon as I enter the space, I struggle. The context tells me that I should sit down quietly along the edge of the room but I want to get close to better inspect the performance’s elements. I cannot be sure what Liliefeldt wants. While durational performance does not typically relegate the public to a specific perspective, contextual protocol prevails and instead of roaming through the space to better understand the relationship between the scattered objects (a glass filled with red liquid, rolls of masking tape, a timer…), I make my way to an empty spot against the wall. I reassure myself that as the work unfolds, the information will be unveiled, yet my urge to get closer does not dissipate. Throughout Liliefeldt’s performance, only one person leaves the margins to walk though the space to get a closer look. For the entire time she cohabits the work, I am incredibly jealous of her bravery. I feel like the context imposes a frustrating distance between me and the work. Proximity, I learn, is something I value in performance, something that I have come to take for granted.

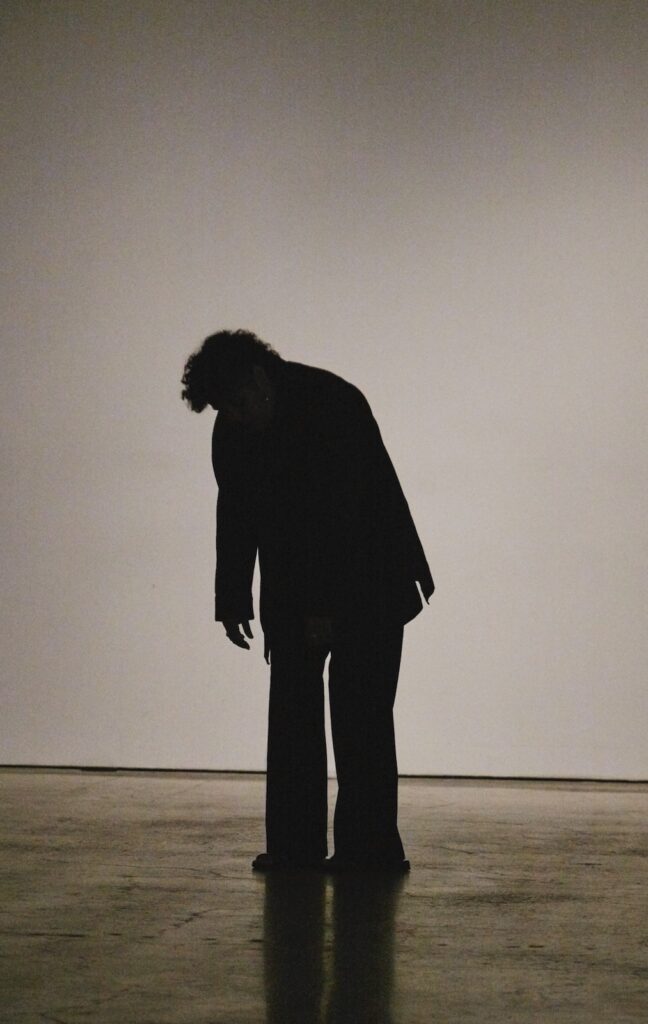

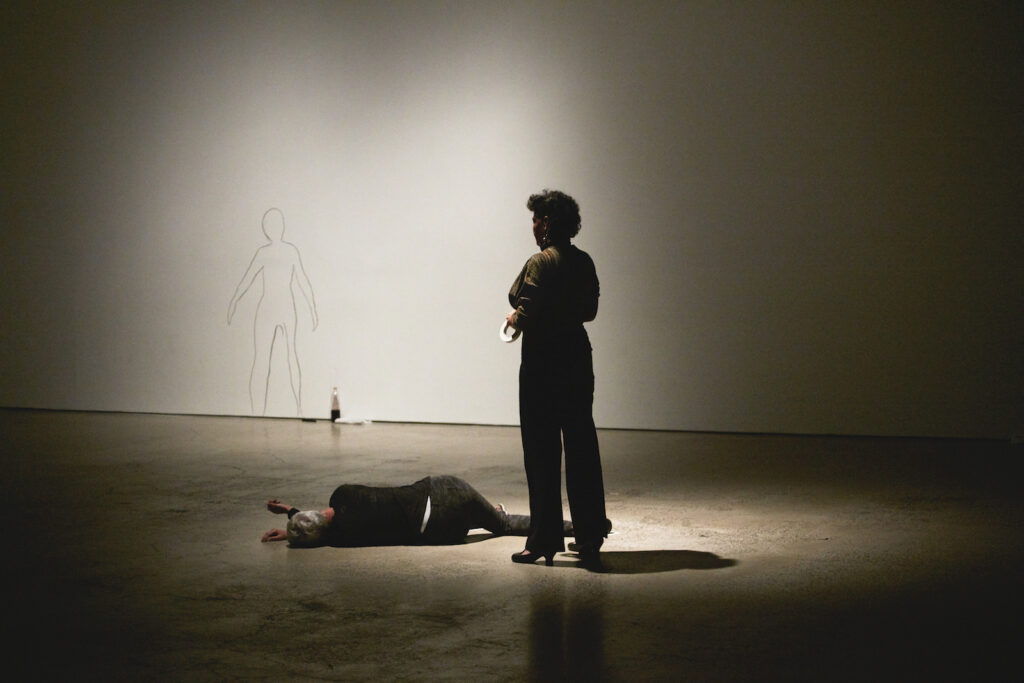

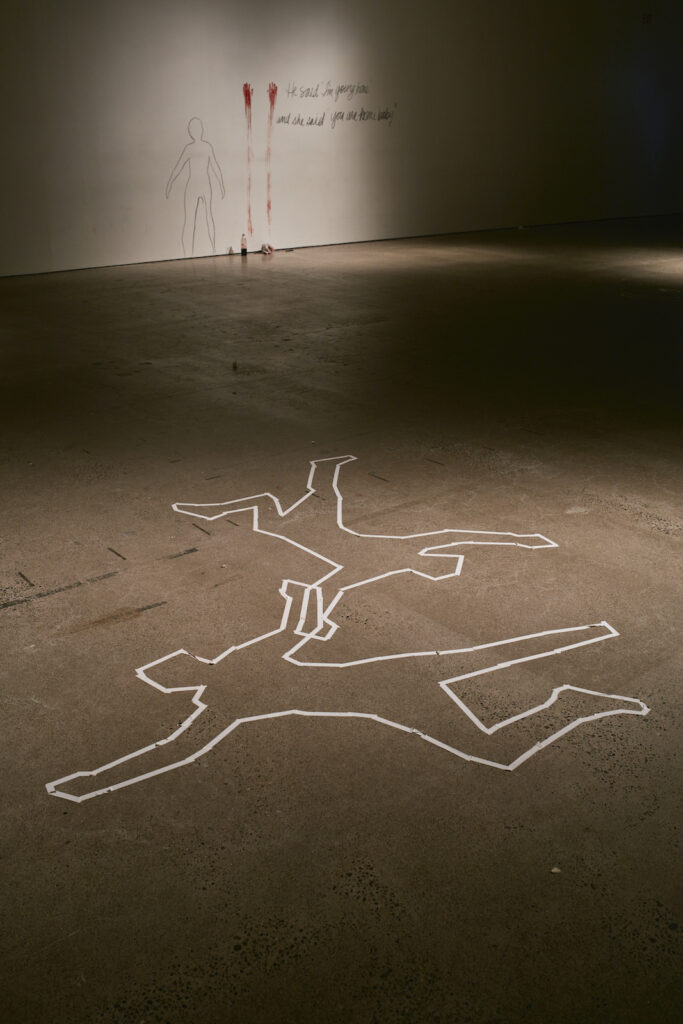

When I have settled in my place, Liliefeldt is sitting in a very commanding hand-carved wood chair. There is another body lying on the ground close to one of the walls. I stepped over it when I arrived. These two bodies are complemented by a silhouette traced in a thin black line on the back wall of the space. This mark, a ghost body, will multiply. But first, Liliefeldt changes her shoes, walks over to the laying body, grips its feet and drags it laboriously across the room and into a spotlight. The body softly contorts and comes to rest. Liliefeldt traces its outline in masking tape. This exact series of actions will repeat throughout the piece, becoming a chorus that bridges one act of mark making to the next.

In addition to the silhouette already on the wall (and the ones accumulating on the ground in tape) four more drawings are made in the space. All are portraits. The second and most abstracted, emerges when Liliefeldt gets on her hands and knees in the middle of the room, sips thick red liquid from a plastic cup, then, moving her body in contorted arches, lets the liquid drip from her mouth into a puddle on the floor. The third portrait occurs when Liliefeldt eventually returns to the wall. Because durational work is often built on cyclical repetition and accumulation, I expect a new silhouette to be traced. Instead, the artist pours red liquid onto her hands, positions herself facing the wall with her hands above her head and lets the weight of her body drag to produce two violent red lines. This body is unquestionably a reproduction of Anna Mendieta’s Body Tracks. I think back to the other actions and begin to retroactively connect them to Mendieta’s corpus. It is not so difficult. The fourth and fifth bodies are textual ones, two quotes capturing an exchange between an anonymous “him” and “her”, interrupted by another pause in the chair.

He said I’m going home

and she said you are home baby

Having given disembodied voice to disembodied bodies, these portraits close the action.

Liliefeldt then grabs the lying body and drags it out of the space. Ironically, now that the artist is absent I can finally get a closer look of the traces and bodies she has left behind. But maybe this is not so ironic considering that museums are places for the dead.