Jenny Keith | May 13, 1969 – March 10, 2023

Jenny Keith, one of the co-founders of the 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art, died earlier this year at her home in Picton, Ontario. Jenny was a key fixture of Toronto’s art community in the 1990s, a passionate and enthusiastic contributor to the city’s lively film, video, and performance art scenes. Her ambitious vision and fierce individualistic streak were tempered by a strong commitment to values of collectivity and community-building. I remember her as both a catalyst and a leader who devoted countless hours to forging alternative models to Toronto’s then-existing artist-run infrastructure, pushing up against a broader arts community that was seen to be stultifying under the pressures of public funding scarcity and a failure to accommodate diversity. After graduating from the Ontario College of Art’s[1] New Media department in 1990, Jenny established herself as a founding member of various artist-driven collectives, including Shake Well and Symptom Hall.[2] She aptly described her interdisciplinary art practice as “embedded in a do-it-yourself activism gleaned from adolescent immersion in punk culture.”

When I met Jenny in 1996, she was managing Symptom Hall, a funky, flexible space on Claremont Street—since torn down and replaced by town homes, alas—that had previously served as a Lithuanian community centre. Symptom Hall, which ran from 1993 to 1998, operated without public support, run by a volunteer group of artists. I knew it as a hub for Toronto’s underground art scene, hosting concerts, film screenings, multidisciplinary exhibitions, performance art soirees, grassroots activist events and arts fundraisers. The main floor featured a large open room with hardwood floors and a stage at one end. The hall was lined on two sides with a series of wooden doors that opened onto a kitchen, various small rooms and closets, and a stairwell leading to an unfinished basement used primarily for storage but also occasionally as a site for art installations and performances.

In November of 1996, I rented Symptom Hall for a month to present Askance, a project that connected my performance art practice with my involvement in the radical faerie movement. I took up residence in the hall along with a cohort that included my partner Ed Johnson and faerie zine publisher Jules International, turning the building into a live-in art installation where we hosted numerous events, including daily drop-ins where I would craft individualized, interactive performance rituals for visitors, slumber parties with readings and story-telling events, afternoon teas, and even a five-day urban faerie gathering where visitors came and camped out in the space. Far from being fazed by this unlikely public intervention, Jenny found it appealed to her punk (and also hippie) sensibilities. Jenny spent many hours hanging out in the space, allowing the two of us to get to know each other and to compare our experiences working at the organizational edges of Canadian art and activism.

Jenny’s radar, however, was keenly attuned to a larger picture. With Askance, artist colleagues whose friendship I had cultivated since moving to Toronto in 1991 intersected with an entirely different set of artists, many coming out of OCA, who had coalesced around Symptom Hall. Jenny sensed in this intersection a kind of critical mass. In 1996 there was a veritable explosion of performance art activity in Toronto, spearheaded by various art collectives and individual organizers. Jenny saw this as an opportunity, and she was ready to seize it. Within days of the conclusion of Askance, Jenny called a meeting at Symptom Hall, inviting a number of different collectives and individuals producing performance art in Toronto to come together for a discussion.

Jenny’s agenda for this meeting was to foster nascent connections, making sure everyone was aware of each other and their work, to acknowledge this proliferation of performance art activity, and to talk about what we might do to support its continued development. She had no preconceived idea of what that support might look like; she just saw something important happening, and she wanted to nurture it along.

A total of 24 people showed up to that first meeting, which took place in January of 1997. What emerged from our discussion was a decision to host an international performance art festival.[3] By early August of 1997, 13 of the attendees of that first meeting presented the first 7a*11d festival, an ambitious five-day event featuring five distinct curatorial series/exhibitions in various downtown locations, including Symptom Hall.

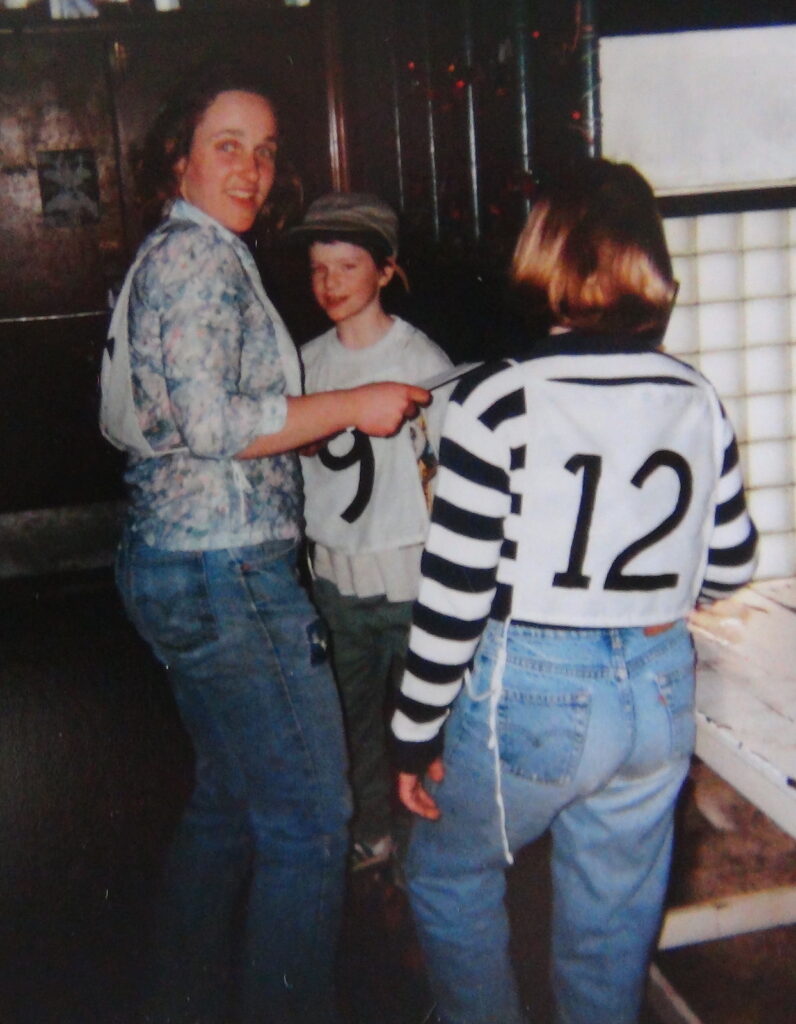

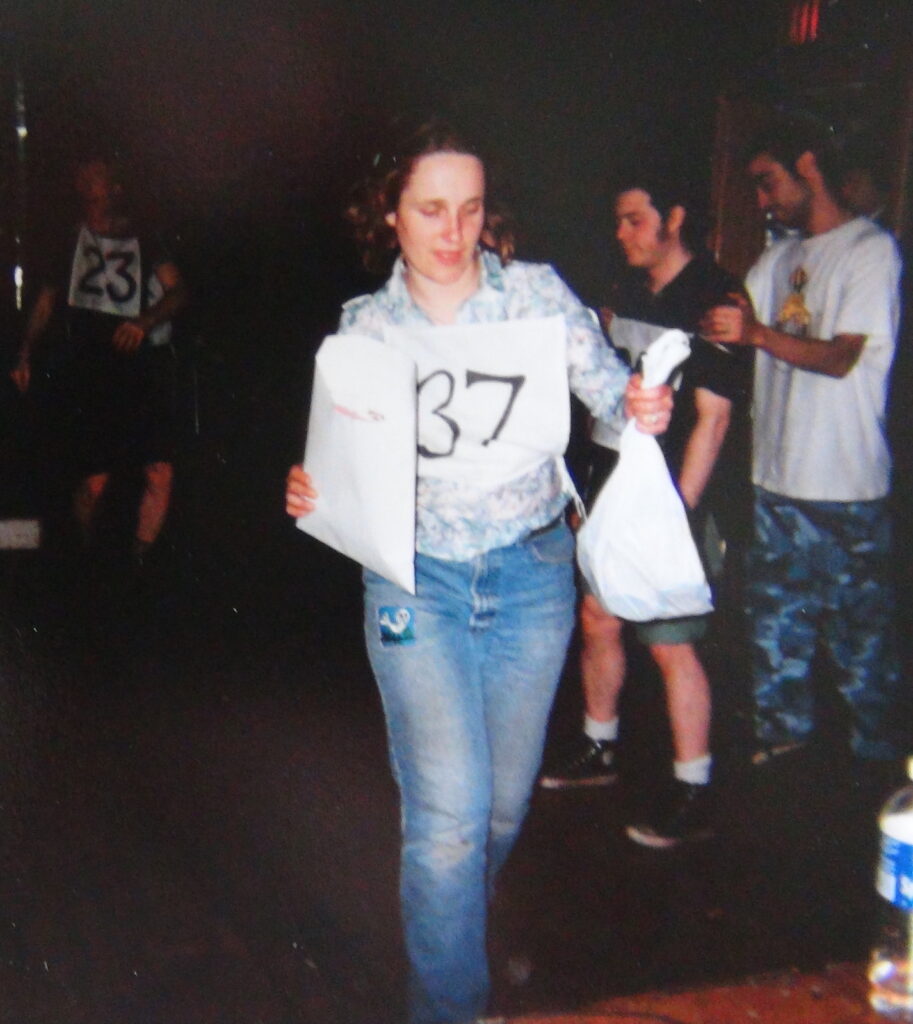

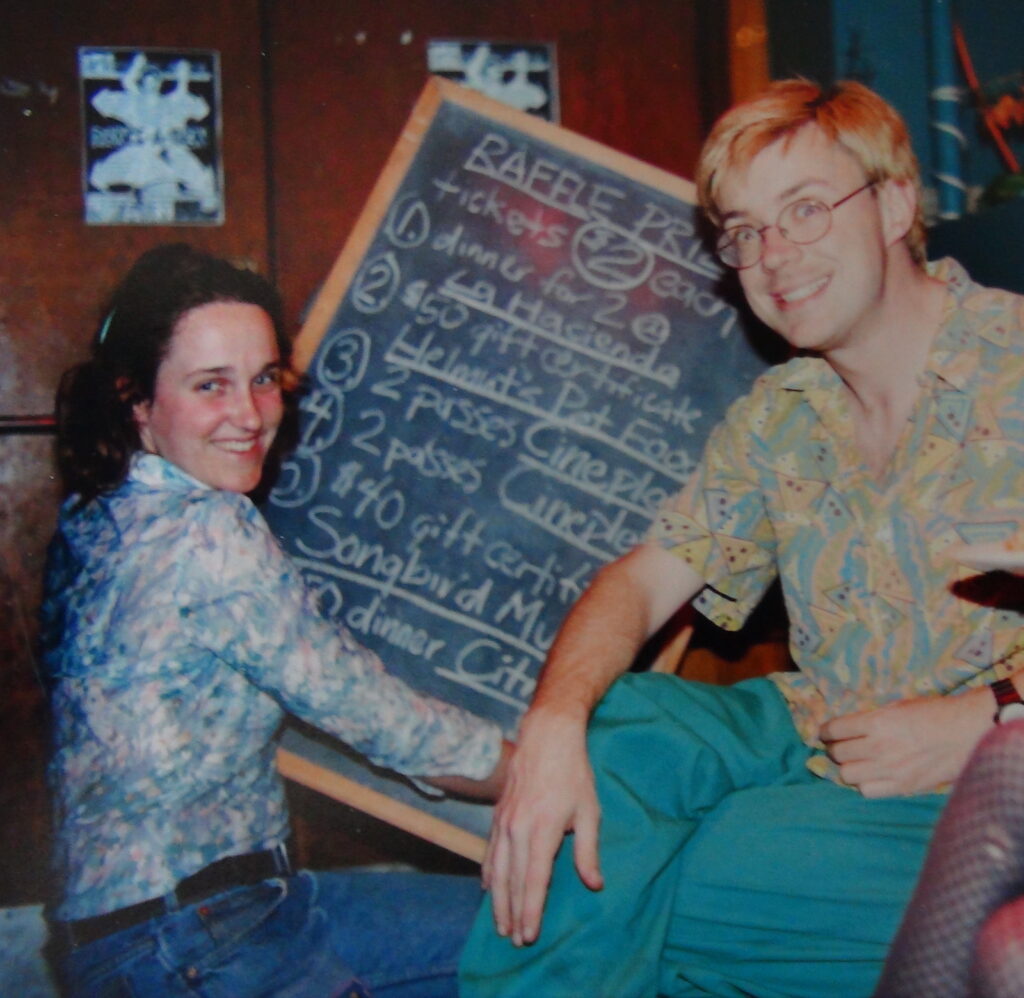

Going from a roomful of strangers with a vague affinity to a full-fledged international festival in seven months is no mean feat, and Jenny worked tirelessly to ensure the project’s success. She organized meetings, assembled technical expertise, co-wrote grants, secured donations, helped process artist submissions and also offered up Symptom Hall for a number of wacky fundraising events/happenings, including a Dance-a-thon and the tongue-in-cheek BEAUTIGANZA, an evening of cabaret performances, DJs, and “beauty stations” where attendees could have their “nails, hair, lips, feet, and sore muscles revitalized,” culminating in a midnight beauty pageant open to all (“Bring your own sash!”).[4] In retrospect, these fundraisers were absurdly labour-intensive for the amount of revenue they produced, but aside from the money generated, they also served a much broader set of purposes—honing our organizing skills, teaching us how to work together as a group, creating a public profile for the festival, and perhaps most importantly, generating a rich sense of a Toronto performance art scene. More than 25 years later, my memories of those days remain vivid.

Jenny Keith and various participants at Dance-a-thon fundrasier, 1997 PHOTOS Derek Mohammed

Quite aside from the organizational logistics, the nascent group also faced the task of developing compelling curatorial propositions. An elaborate call for submissions invited artist proposals for the various programs being developed by subgroups under the umbrella of the festival. Although Jenny was managing Symptom Hall, she was not interested in overseeing the festival programming that happened there. Instead, she chose to focus her curatorial efforts on a program that activated Trinity Bellwoods Park with site-specific and environmental performance art works. Working with Terril-Lee Calder and Derek Mohamed, she developed an ambitious series called Sediment that ran the course of the five-day festival and featured 9 different projects by artists and artist groups.

Sediment featured performances attuned to dynamic, site-specific elements such as light, weather, pedestrian traffic, and the local soundscape. The title of the series pointed to a conscious recognition of the complex geography and history of the park. Trinity Bellwoods is part of a larger patchwork of Toronto parks that follow the outline of what was once Garrison Creek, which the curatorial description of Sediment describes as “a meandering waterway/ravine, masquerading as a sunken park system.”

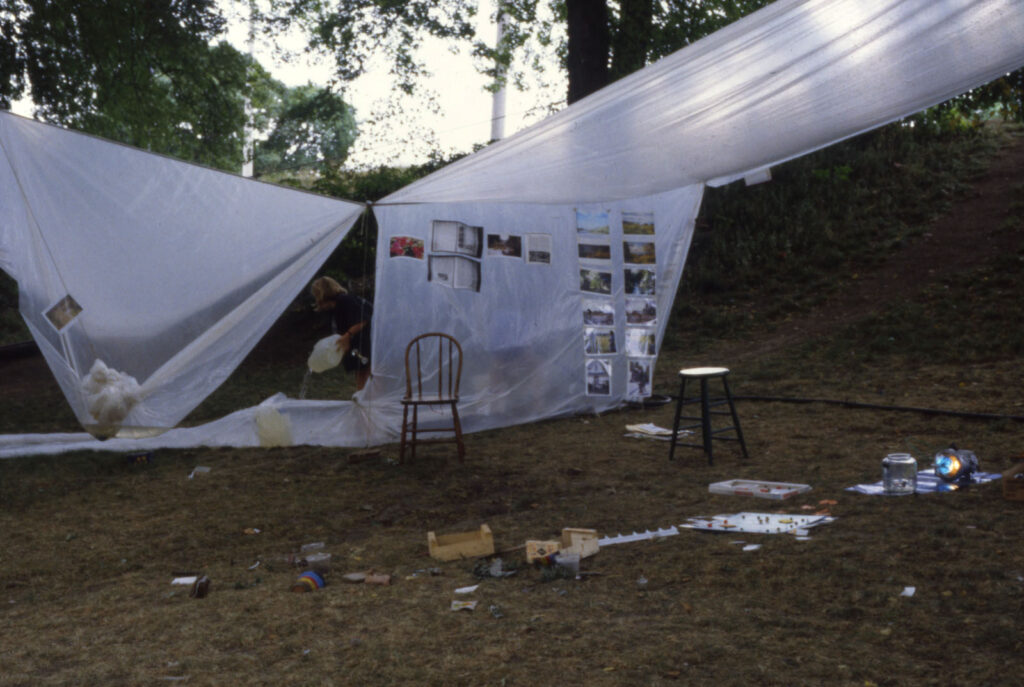

Sediment offered a rotating roster of temporary occupations of Trinity Bellwoods’ various terrains and temporalities, with appearances by costumed figures, swirls of human bodies in motion and tableau, whispers and rhythms, sound and light projections. Jenny’s immersion in the project was total. For the duration of the festival, she lived in a van parked in the “pit” near the park’s northern end, which also became the site for her cumulative installational performance work, sur, blue, round.

The piece featured a family-friendly encampment constructed using thick, semi-transparent plastic sheets as tarps. Plastic sheets were strung among and between the trees to suggest two walls and a roof, but the structure remained open on two sides. The result was a recreational space, fed by power from a generator, that was as much outside as inside, with the grassy ground as a floor and the surrounding green of the trees and blue of the sky visible through the blur of the plastic walls as well as the open sides. Scattered within the partially enclosed space were chairs and stools, lamps, a shelving unit stocked with books and board games, and a wooden bench holding a small television set.

Parts of the plastic structure were also used to collect and contain water, with both a hanging pool and a snaking track that symbolically resurfaced the buried Garrison Creek. Jenny animated the space through performance actions at sunrise, noon, and sunset each day, with Polaroids and printed photos linked to her daily actions gradually covering the plastic walls.

In keeping with Jenny’s artist statement at the time, sur, blue, round “explores the intersection of technology, identity and environment, inspired by a visceral and emotive appreciation of landscape.” As a low-tech, makeshift shelter for living, doing, and gathering, sur, blue, round also amplified many of the concerns and strategies evident in the overall curation of Sediment. The work framed both the park’s landscape and the consciousnesses of its human occupants as permeable and interweaving palimpsests, where the sedimentary layers that give shape and contour include not only material debris, but also more ephemeral but nevertheless cumulative washes of movement, sound, light, temporary juxtapositionings, and even imaginings. Human activity and technological intervention may reshape the land, leaving physical and energetic traces, but it is no less true that we as creatures open onto our surround in ways that mark us. The landscape blankets and permeates us, triggering impulses that are felt as sensation and retained as memory. Human and landscape are linked in ongoing and at least partially reciprocal cycles of accretion.

Installation views of Jenny Keith’s sur, blue, round 7a*11d 1997 PHOTOS Cheryl Rondeau

Of course, digging through sediments to read and revisit history—or memory—is a subjective and selective process. In retrospect, for example, my appreciation for the Sediment project is definitely greater now than it was when it was happening. The individual artist projects, and the ways in which they related to each other and the site, have gained resonance over time as some of the glitches in their execution have faded while their underlying intents have seemed to deepen and clarify. I am also aware that my affirmation of Jenny’s essential part in the origin story of 7a*11d elides a great deal of tumult and tension (sharp words and sharp elbows) that were an undeniable part of those raucous, chaotic beginnings. It was not always easy for all of us to get along, nor evident what paths would be the best to follow. Not all of our dreams came true. Symptom Hall closed the following year, and Jenny did not remain part of the festival as it moved forward. Soon after, she left Toronto for Prince Edward County.

I do believe, however, that key aspects of Jenny’s generous, ingenious DIY spirit live on in the unique character of the artist collective that has grown out of that initial festival. And I am also certain that the festival’s perseverance is a testament to what Jenny identified in those earlier days as one of her cherished long-term goals: “inciting rampant art activity.” I am forever grateful for her foresight, initiative, and dedication in bringing 7a*11d to life.

NOTES

[1] In 1996, the Ontario College of Art (OCA) was renamed the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD); in 2010 it became the Ontario College of Art and Design University (OCADU).

[2] The Shake Well collective, which included Zoë Hamilton, Jenny Keith, Kim Kutner, Clare Lawlor, Louise Liliefeldt, and Joey Myers, organized performance events in the early 1990s. For a brief description of the collective and their close relationship with Symptom Hall, see Doyle, Judith. “Life & life support systems: Zines, nets & outlets by artists — the late ’70s & some now.” Fuse Magazine vol. 19 no. 5, 1996, 23-33. ISSN 0838-603X Available at http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/1907/

[3] The idea of an international festival was fresh in people’s imaginations in part because of an event Fado had sponsored at the end of October 1996, a collaboration with the Rencontre internationale d’art performance et multimédia organized by Le Lieu in Quebec City. In conjunction with the Rencontre, director Richard Martel had put together a regional tour for several of the visiting artists, with stops at artist-run centres in Granby, Alma, Victoriaville, Joliette and, hosted by Fado, in Toronto. The three-day Fado event, conceived by Fado cofounder Sandy McFadden and coordinated with the assistance of Istvan Kantor and me, used CineCycle and several street locations, including the storefront window of what was then Pages bookstore on Queen Street West. The Toronto event was by far the largest of the tour, featuring 10 artists from the Rencontre as well as Martel himself, along with five additional local artists curated by McFadden. If I recall correctly, Johanna Householder, who had written a review of the Fado event (reprinted in Fuse Magazine) for a post-event catalogue put out by Le Lieu, was the first to propose that the group meeting at Symptom Hall organize an international performance art festival.

[4] Quotes taken from the press release for the event.