By Alison Cooley

Andrée Weschler moves with the confidence and surety of someone enacting a familiar, precise and practiced routine. Opening Garbage bag & love seeds, Weschler strides into the studio with a chair. She wears a light pink nightdress, stockings, and shoes. Carefully removing her footwear with a nonchalance evocative of the commonplace motions of preparing for bed, she brings a few simple materials into the scene with her: a fishbowl, a reusable grocery bag laden with some as-yet-unseen material, an industrial-sized black garbage bag.

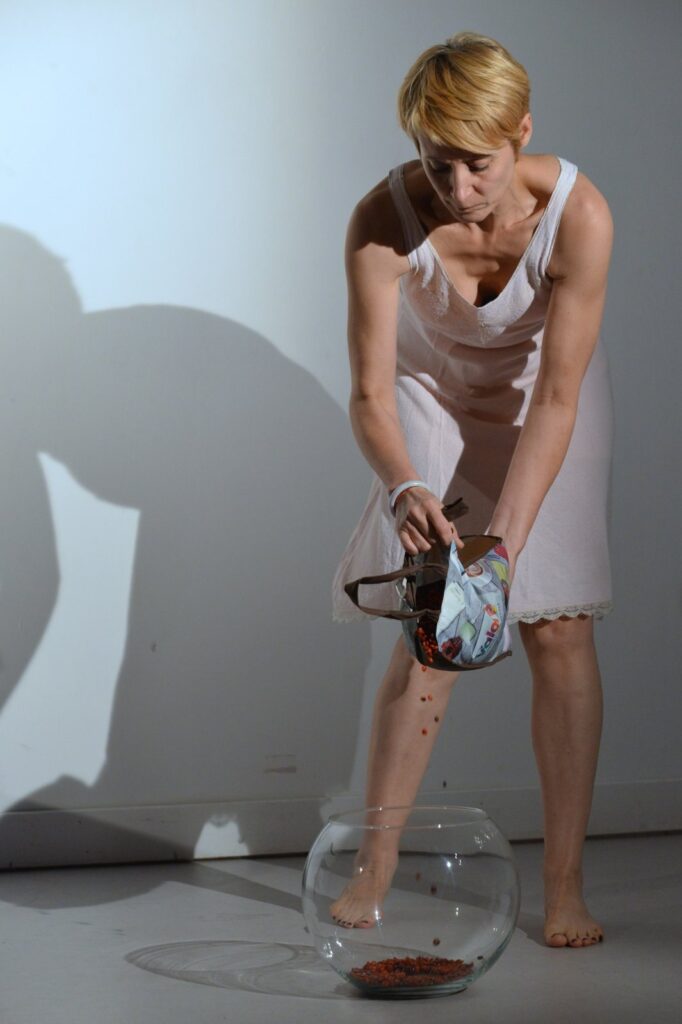

As Weschler begins to empty her grocery bag into the fishbowl, many tiny granual objects ping satisfyingly against each other, bouncing parabolically inside the glass vessel. I mistake them initially for candy— appealingly red and shiny, passably round, ambiguously stradling the boundaries between organic and manufactured. Weschler is particular with these “love seeds,” one of two key materials in her performance. When a few go astray and ricochet off the fishbowl, she collects them painstakingly from the floor. She dips her hands in the fishbowl, evoking a perfectly chaste erotics of tactility.

Over the course of the next several minutes, Weschler enrobes herself in the garbage bag, and pulls the fishbowl in, dumping the seeds in with her. As she burrows into the space she has enclosed, Weschler closes the entrance to the garbage bag, trapping herself, the mysterious seeds, and a reserve of breathable air inside. Soon, her audible bag-breath becomes laboured, indistinguishable from ecstatic breath. She squirms inside the bag and among her breath we can hear the occassional rattling on the seeds as she moves. The clinging plastic defines the shape of a leg, the curve of a shoulder, but also gives the impression of a united mass distinct from Weschler’s human body. It recalls cheap bondage leather, and as Weschler’s breathing becomes heavy inside, a parallel association with erotic asphyxiation.

Weschler’s erotics is not a prepackaged set of kinks and toys, although it borrows some of their language. It is also an erotics of material exploration— an inquiry into the qualities the garbage bag and the love seeds represent, qualities which are both personal and culturally specific. Amidst this highly personal and strange erotics, I find myself preoccupied with the significance of the love seeds. Although to me, they immediately resembled small candies (in the vein of cinnamon hearts or miniature m&ms), they are actually the seeds of Adenanthera pavonina (also known as the saga tree). In Singapore, Weschler’s current home, they are a regular natural reality, and fall amongst leaves under the saga. Like cinnamon hearts, the saga seeds have an existing association with love, but in Weschler’s hands, their meaning shifts, gets stuck mid-contact. Preciousness and multitudinousness endure in the red, hard seeds, even as Weschler undulates through her mysterious relationship to them. Eventually, she reaches a breaking point. Weschler’s foot bursts through the plastic, and soon the spillage of seeds out onto the floor invites a new exploration. Her final gesture of pouring the remaining contents of the bag back into the fishbowl, and allowing the rest of the strewn seeds to sit in place on the floor, proposes a new engagement with these mysterious materials. Weschler plays out a personal, tactile relationship, and lets us imagine what our own might look like.