By Paul Couillard

Frank Green | July 28, 1957 – January 23, 2013

Frank Green—activist, writer, arts critic and performance artist—died in 2013 at the age of 55. Online obituaries pointedly identify the cause of his death as being complications due to AIDS. But how to unpack the paradox behind those words?

When Frank Green appeared in the first 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art in 1997, he had a reputation as an HIV warrior. Using performance art as his platform, he questioned the causal links between HIV and AIDS in his widely toured work, The Scarlet Letters, bravely submitting his own body into the public record as his primary dissenting evidence. His story was a powerful one: HIV-positive from the mid 1980s (and in retrospect, how could it have been otherwise, given his personal history as a bisexual drug addict in New York City?), he had watched many of his friends and colleagues die of AIDS, and had become depressed and sick himself as he laboured under the grim, seemingly inevitable diagnosis that “HIV=AIDS=Death.” Then, surprisingly, he had come to his senses, shrugged off this death sentence, and returned to health.[1] His conclusion: it was not the virus that had been making him sick, but a belief in his own powerlessness in the face of it. More than anything, he refused the status and stigma of victimhood, and for a long time, he was buoyed by that refusal. It took nearly two decades for the particular HIV strain in his body to trigger a life-threatening illness, and another decade before he finally succumbed to a version of the equation that he had so vehemently challenged.

In deference to the smart, witty, and frequently sarcastic Frank Green I met in 1997, I defy those who would read his story as one of simple tragedy or ignorance. He was certainly not wrong to suggest that the medical establishment of the 1980s and ’90s did not have a complete picture of either HIV or AIDS; nor was he wrong to question why so many seemed to die so quickly of AIDS while others with an HIV-positive diagnosis could live symptom-free for years. He was certainly not wrong to be wary of the catastrophic effects that early treatment protocols involving largely untested drugs and uncertain dosages had on a generation of gay men. Given the profound shortcomings of the care available at the time, Green’s focus on self-healing reflected a highly rational impulse of self-preservation. Most importantly, he was quick to recognize that his HIV status gave him a very particular perspective that was both useful and instructive for revealing the various politics underlying science, medicine, and public and personal health.

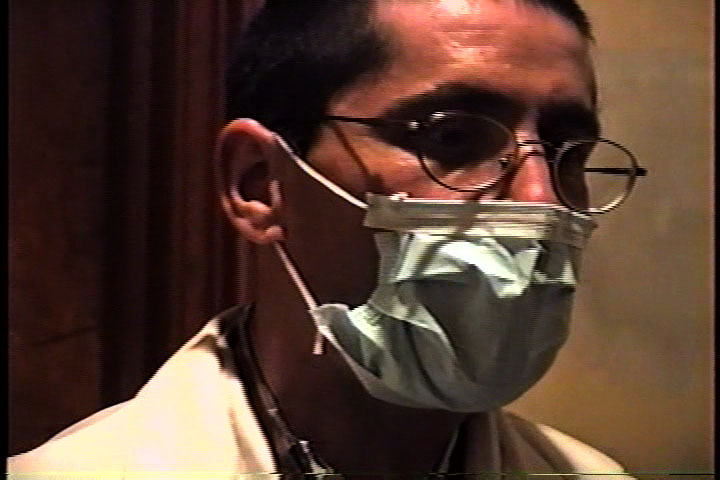

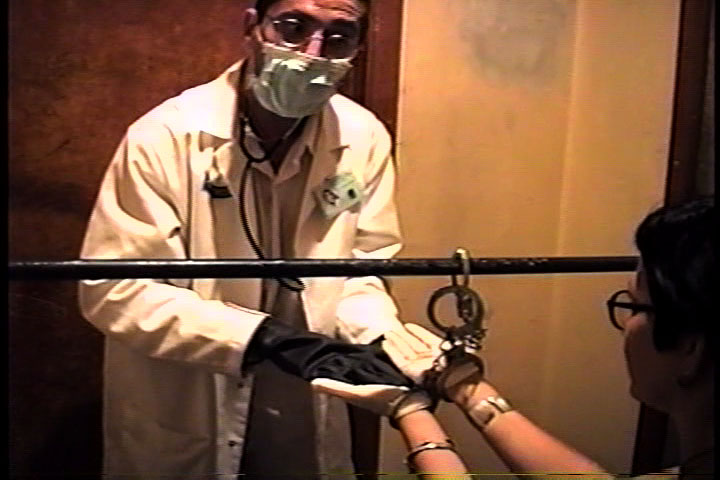

By 1997, he had moved on from making autobiographical work about his own HIV status, and was taking a closer look at the social and power dynamics of the patient-doctor interface. The work he presented in Toronto, entitled Anonymous Test Site, offered an interactive experience that replicated, ad absurdum, the process of being tested for an undefined contagion. Green enlisted two Cleveland colleagues and several Toronto performers[2] suited in latex gloves and surgical masks to enact various clinical roles—intaking the audience as “patients,” administering questionaires, collecting fingernail clippings and scrapings, and directing participants to waiting areas—until finally, the hapless test subjects would be led, one at a time, into a small room. There, they were handcuffed in a kneeling position to a metal bar and left alone in the dark, to await “the doctor”—played by Frank himself. He would appear, direct a glaring light toward the subject’s face, and proceed to offer vague (and vaguely sinister) advice on hygiene and public comportment to be followed while the participant awaited a diagnosis, promised to be delivered a few weeks hence once the samples had been analyzed. Released from the handcuffs, the chastened subject would then be sent away in this unsettled and inconclusive state.

If the tone of Anonymous Test Site was cynical, it nevertheless had an earnest and urgent quality in its insistence on placing the bodies of its audiences into a simulated line of fire that has been—and continues to be—familiar to too many of us. By satirizing the testing process, Green hoped to push his audiences to a more critical and assertive stance in relation to medical practices. We can be so quick to give away our agency in the face of authority, so ill equipped to assert our self-knowledge and lived bodily experience in relation to established medical discourses, so easily mesmerized or silenced by the institutional langauges and procedures of health care systems. However much may have changed in terms of western medicine’s understanding and treatment of HIV infection, Green’s parody of the interface between patients and the health system remains eerily apt.

Though I did not know then that Anonymous Test Site would be Green’s last major performance art project, as an organizer of 7a*11d, I considered us fortunate to be able to produce this ambitious work and to host such an energetic and charismatic artist. Our first festival was an ad hoc affair, put together on a shoestring budget. Frank’s agreement to participate was an important gesture of support on the part of an established artist who valued our initiative and recognized our potential. Coming from Cleveland, he also provided us, at least in my mind, with a link to what was then one of the collective’s key inspirations: the Cleveland Performance Art Festival.[3] I remember remarking to Frank how lucky he must feel to be working in a city with such an important, established venue for presenting performance work. Ever the incisive critic, Frank noted that in his view, the Cleveland festival was, at best, a mixed blessing. Rather than providing an engine for generating local activity, he felt the festival had produced the opposite effect. By taking up all of the available resources for alternative art production, the festival had made it difficult for any other performance art venues to develop, effectively killing any sense of a grassroots scene.

Having never been to Cleveland, I cannot say whether or not Frank’s assessment was an accurate one; but I never forgot his comments. In fact, they have had a lasting influence on my mindfulness as a performance organizer and curator. Undoubtedly, they have informed how I have contributed toward the shaping of 7a*11d’s development[4] within a larger artistic ecosystem.

Although Frank died well over three years ago, I only learned the news recently, as I was tracking down artist permissions for 7a*11d’s new online video archive of performance documentation. Revisiting Green’s connection to 7a*11d, I cannot help but feel a complex, untidy swirl of conflicting emotions. Frank’s story stands at the intersection of two potent influences that have shaped my own history: performance art and AIDS. One has been an endless source of adventure and enrichment for me, while the other has produced an irreconcilable deluge of loss. One points to the blessings of ephemerality as an infinitely bountiful and joyously unpredictable generator of presence, of meaning, and of lore—while the other points to ephemerality’s perils as a relentless annihilator that seems to take away all the best lives and moments too soon.

Green, who managed to secure a number of productive and engaged post-addiction, post-diagnosis years of life for himself would, I am certain, have us direct our attention toward ephemerality’s blessings. Certainly his example does. I salute the ambitious passion for life, the uncompromising directness, the keen intelligence, and the embracing sociability he shared with us.

—Paul COUILLARD

—

[1] For his own account of this journey, see Frank Green, “Resisting Victim Status: Art Against Medical Nemesis,” Journal of Medical Humanities 19: 2/3 (1998): 127-131.

[2] Thea Miklowski and Holly Wilson traveled with Green from Cleveland, and were joined by local artists Michelle Allard, Churla Burla, Lucia Cino, and Curtis MacDonald.

[3] The Cleveland Performance Art Festival ran for 11 years, from 1988 to 1999, and was at the time the largest festival of its kind. Although 7a*11d chose not to replicate Cleveland’s hierarchical structure of varying support for artists based on their perceived stature, we did shamelessly copy the design of their application forms.

[4] And, it should be mentioned, the development of FADO as well, where I was the Performance Art Curator until 2007. Frank Green’s work at 7a*11d was presented as part of a FADO series entitled Five Holes: Touched. FADO was one of several performance art collectives and organizational entities that produced work under the banner of the 7a*11d festival in its early iterations.

Frank Green was an artist and writer based in Cleveland, Ohio. After studying filmmaking at Kent State University, he moved to New York in 1980, appearing in East Village clubs including the Limbo Lounge, Pyramid, ABC No Rio and Club 57. Returning to Cleveland in 1988 to kick a cocaine and heroin addiction, he discovered he was HIV positive, and spent the next several years practicing his art as a ritual of self-healing. He worked in various media, including audience participatory events, monologues, multimedia spectacles, and installations. A six-time Ohio Arts Council fellowship recipient, he performed throughout the U.S. and Canada, and was a regular art critic for the Cleveland Free Times, an alternative weekly newspaper. He was featured in the first 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art in 1997 as part of the FADO series Five Holes: Touched.