By Daniel Baird

Most performance artists insist that what they do is distinct from what is disparagingly termed “mere spectacle.” I take this to mean something like this: performance is not reducible to the images it might result in, which can be remarkably beautiful or grotesque, but rather consists in the ineluctable series of acts that unfold in time. This may seem obvious, or tautological, but it’s important to keep in mind right now since the work of some of the most influential performance artists, like Marina Abramović, is largely experienced through finely staged and crafted documentation, and is now conceived in a way that performances can be restaged like theatre events, sometimes decades after the original performance. Yet it is the specific, vanishing singularity of actions in time that gives performance art its distinctiveness, and is also the place where the boundary between art and life begins to blur.

The Fluxus artists famously insisted that no real distinction should be made between art and life—art is life, and life is art. This, of course, raises the broader philosophical question of what constitutes “life” and “art” in this context. These questions were given special importance for me this morning when I headed off in search of karen elaine spencer’s performance in Union Station, which was scheduled to take place between 9 am and 5 pm. I purposely did not investigate in advance the nature of the performance but rather went there cold, hoping to encounter it accidentally like any other passerby on his way to catch a train to Montreal or Winnipeg. This proved considerably more difficult than I had expected. Lurking in front of the station, I found myself focusing in on a short, compact woman somewhere in her thirties dressed in tight jeans and a windbreaker, her straight blond tamped down by a toque. She looked upset, agitated, standing beside a suitcase packed to the point of bursting. Occasionally she stamped her feet as though about to launch into a tantrum, muttered to herself, and walked out in a semi-circle around the plaza in front the station. She did this repeatedly with such precision it struck me that it was part of a routine, and I was convinced that she was karen elaine spencer and that this was the scheduled performance, or at least part of it. At some point she pulled an iPhone out of her pocket, stared at its screen, and began to cry, and I started to feel uneasy about the fact that I had been standing there watching her and even taking notes for a long time—after all, she might not be karen elaine spencer! Then a woman I gradually realized was probably her mother arrived and she started yelling, in French, about how she had too much luggage with her, how she had to get rid of some things, and her mother told her that she had to calm down or else she would miss her train. By then I fully understood that this could not be karen elaine spencer, and that I was not watching a work of performance art, but still I followed them into the station and to the line for the train to Quebec City. She was not karen elaine spencer, was not a performance artist, was simply a woman on her way back home to some sad event, like a funeral. But then maybe she was karen elaine spencer, maybe the performance consisted of posing as someone going to Quebec City under tragic circumstances. Or not. And so forth.

I later learned karen elaine spencer was sick and the performance that day had been cancelled.

Despite the close relationship between art and life, and life and art, with most works of performance art it is fairly obvious that one is encountering a work of art, even if it involves activities that are in some form close to life. Sarajevo-born Canadian artist Bojana Videkanic’s performance, for instance, opened with her decked out in a sleeveless T-shirt and men’s underwear squat on a rectangle of cloth in front of a plastic bowl full of dough, bags of flour and bottles of vegetable oil. Fitted with a microphone, her breathing was loud, raspy, and furtive. First she kneaded a large lump of dough into a loaf shape, and then, setting it down on the cloth, she used a long, wooden rod to begin the process of spreading the dough out into a thin layer. Wetting the dough with oil, she slid her hands underneath it and pressed her fingers with caressing and fluttering movements. Stretched like that over her fingertips, the dough looked like human skin, quivering to the touch. When the dough had been stretched to its limit, Videkanic stood up, smeared messy red lines of paint down either side of her face and body, and began singing a song in Serbo-Croatian, a traditional song that is associated with Bosnia. Eventually she stretched out on the dough, and, singing plaintively and out of tune, she pulled the dough completely over her with just her bare feet sticking out. She looked as though she was wrapped in a shroud. The piece was quietly heartbreaking, evocative as it was of Videkanic’s family and history (her family left in 1995), and of a world that was permanently destroyed by the war.

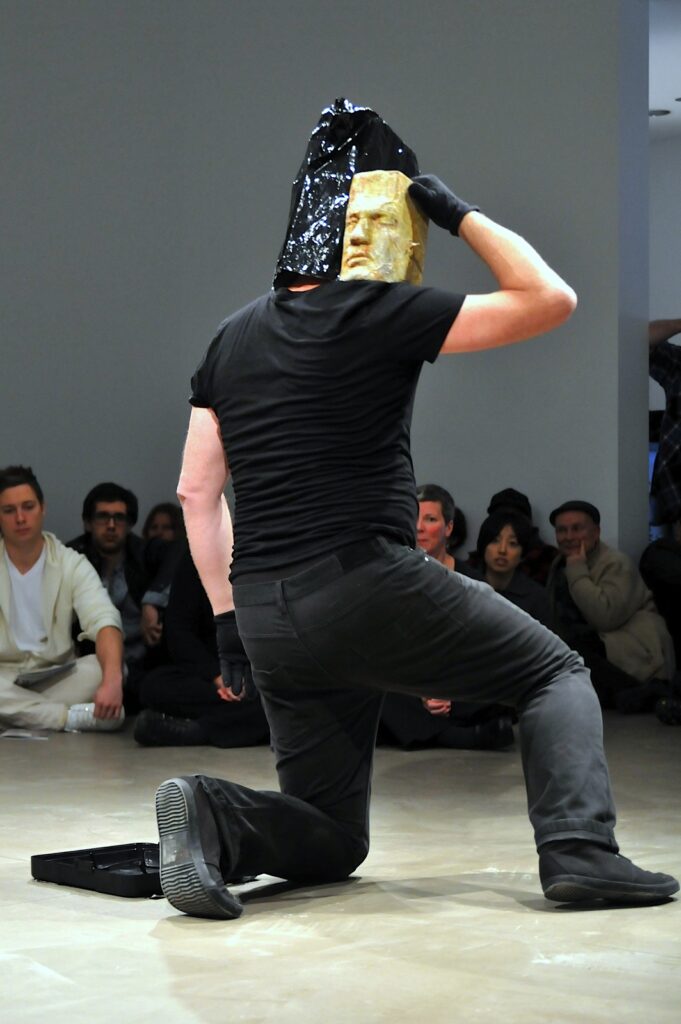

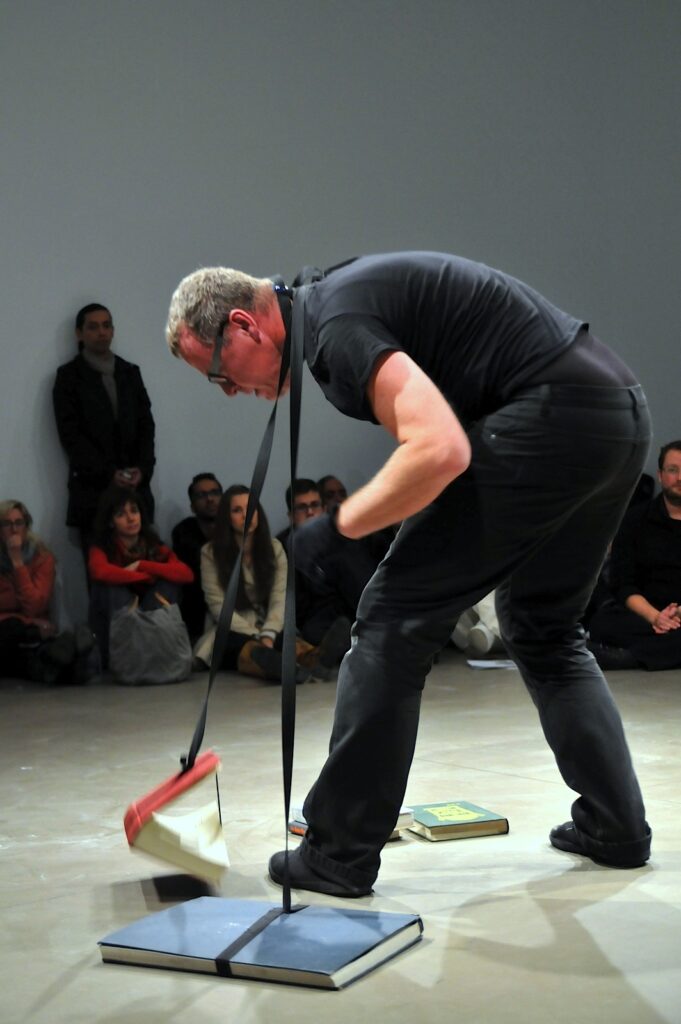

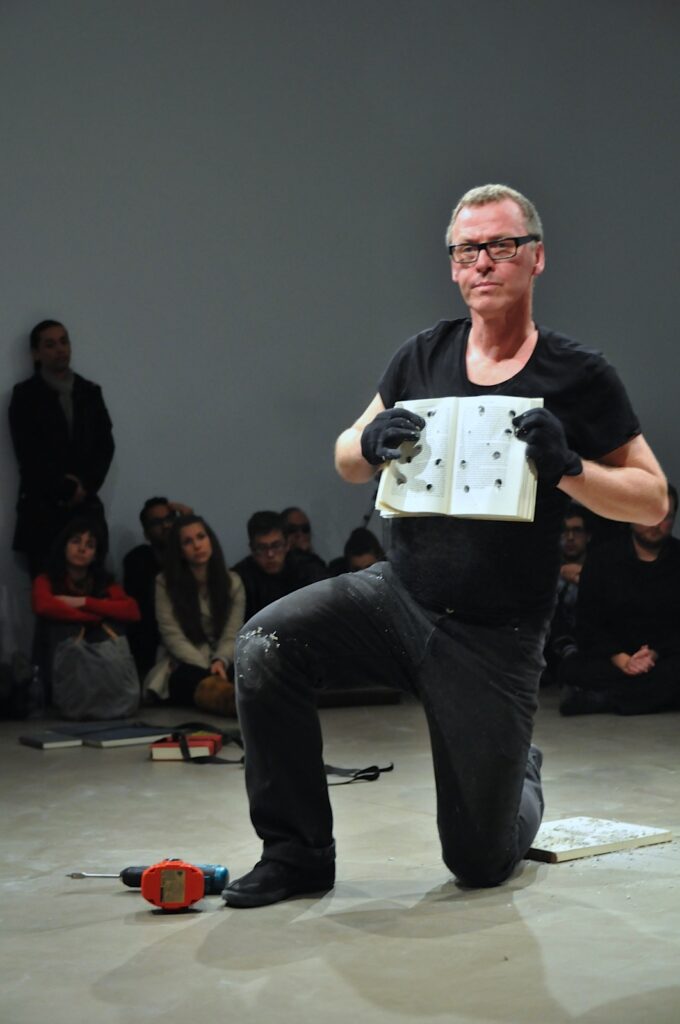

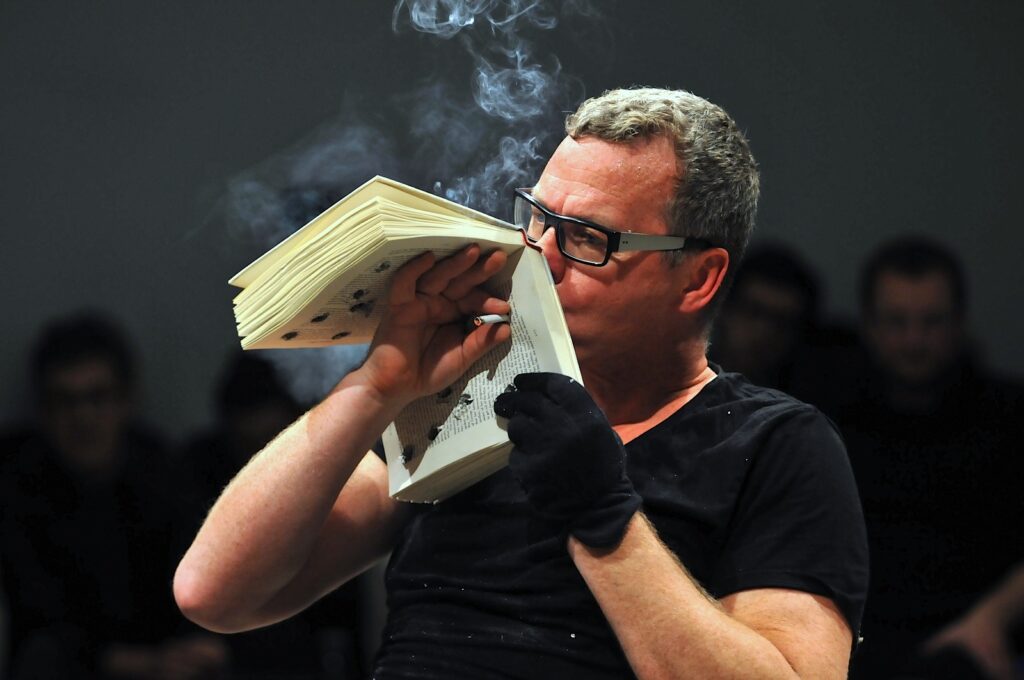

While Swedish artist Joakim Stampe was organizing an idiosyncratic array of props on the floor—a record player, books, a power drill, a can of beer—he commented, “I am going to show you some images I have never seen before.” He rubbed the record player over his body; he put a black bag on his head; he picked up a book whose back was a sculpture of a human face. He put a single on the recorder player, a folk song from the 1950s about an old revolutionary who had lost everything except his socialist ideals—the song was played over and over, to great comic effect, throughout the performance. At one point he put on a glove, wore the book with the face on its cover as a kind of sleeve, and began to touch and probe the audiences, begging for coins; at another point he drilled holes through the book and lay on his back with the book on his face, smoking a cigarette through one of the holes.

Although some of the things Stampe used in the performance seemed to have personal significance—the song was one his father, an artist and blacklisted socialist, liked to play—his performance was less about specific symbols than about discovering new images, new relationships, and new responses.

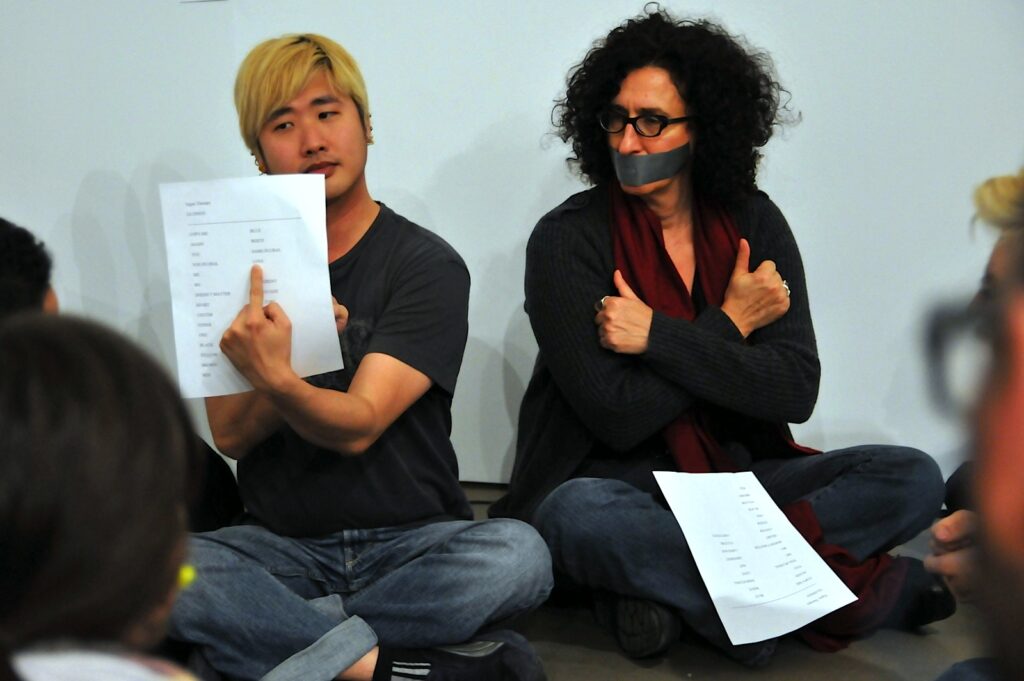

Canadian Jolanta Lapiak’s De-hearingization, on the other hand, takes a wholly different approach to performance than that of Videkanic and Stampe. Rather than focusing on the actions of one or more performers, her piece consisted of orchestrating participatory experiences centered around destabilizing our hearing-centric concepts of language and communication. Accompanied by several other deaf performers, Lapiak had audience members’ mouths taped shut and ears plugged, then they were herded into small groups where they were taught rudimentary sign language without relying on hearing. At the end of the performance, everyone gathered in a circle around a paper chain made from torn-out pages from a dictionary and broke the links in the chain. Like sight, hearing is a fundamental communicative sense, and relating to the world without it inevitably involves shifts in focus and priorities. Lapiak’s performance gestures toward recreating an aspect of this experience for those whose hearing is intact with the aim of making the point that language and communication are not in and of themselves dependent upon a particular organization of the senses.

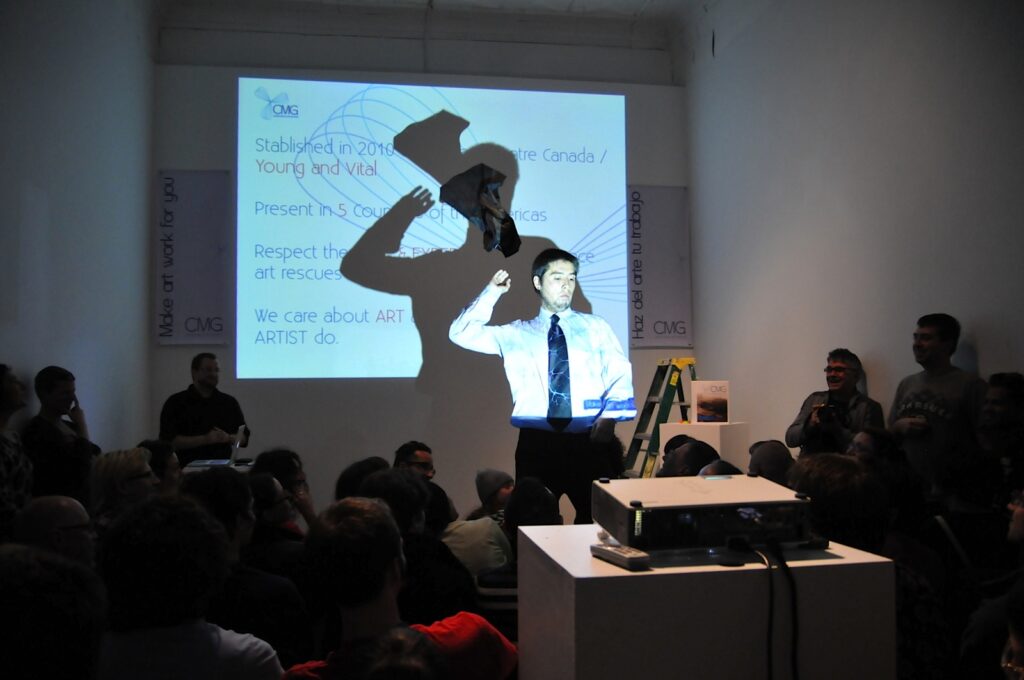

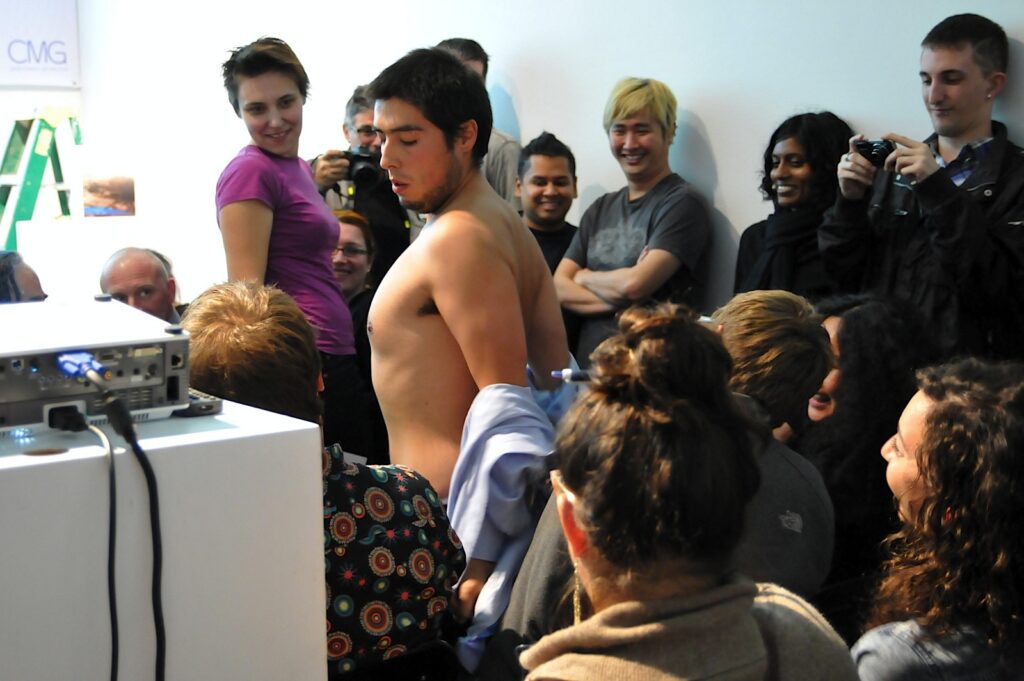

Performance art can be a somewhat heavy affair, trafficking as it often does in big ideas and issues—personal and national identity, the depredations of history and contemporary consumer culture, the unstable contents of the unconscious, the nature of language and art. So it is always a relief, especially in the context of a festival, when there is an occasion to laugh. Bogota, Colombia based artist Carlos Monroy opened his CMG Performance Art Services with a Power Point presentation. “Confident, dynamic, versatile, independent,” Monroy said of his company, which artists were invited to invest in.

“Contemporary, aggressive, ownable….” Monroy’s hilariously disconnected corporate language serves to underscore a feature of performance art many of its practitioners take pride in—that it does not trade objects that can become commodities, that, Marina Abramović aside, it does not depend upon the same star system that dominates most contemporary art. Then, halfway through his presentation, sultry Latin music came on, and Monroy, dancing to the new vibe, moved into the audience and began to strip. Jacket, tie, shoes, socks, shirt, pants, all of it came off as Monroy pumped and swayed his way through the small, seated crowd; by the time he resumed his more corporate personae, all he had on was a big white jock strap. “CMG Art Services,” he said, “Let art work for you!” So much of the art world today is bound up in celebrity artists (Abramović was profiled in the Home and Garden section of the New York Times showing off her multi-million dollar country home!), dealers, collectors, institutions and name curators, and against this background Monroy’s performance was refreshingly naïve and bumbling. He doesn’t really know how to use Power Point very well; and the corporate marketing language is clearly alien to him.