By Daniel Baird

In the early 1980s, Tehching Hsieh conducted his legendary one-year performances, in which he performed a specific symbolic action, or fulfilled a stricture, for the duration of one year. In one, for instance, he punched a time clock every hour on the hour for a year, carefully documenting the instances in which he failed to do so; in another, he did not enter into any building or shelter for one year. Hsieh’s durational performances are among the greatest, most sublime, and most wholly enigmatic works of performance art, and the ones in which the relationship between art and life is most uncompromisingly examined; they also raise pointed questions about what a work of art is and what a performance is. Does performance need to involve actions of some kind, as I suggested in a previous blog, or can it involve a lack of action, a negative action? Can it be just a state of being, a kind of mode of existence, rather than an action? Does it have to be something available to the public, or can it be purely private? Can it be something that can only be seen in its documentation.

Curated by Johanna Householder, d2d.5 = direct to documentation features works that can either only be seen through their documentation, or works that were viewed as more interesting in their documentation than as works to be reproduced live in Toronto. Finnish artist Annette Arlander’s Year of the Rat is in the tradition of Hsieh’s year-long performances. For one year, Arlander went every day to the shore in the Bay of Finland and filled and emptied a jug of the water. In the five-minute version, one sees the passing of the year in fast forward: the tides moving in to cover her feet or sliding out, snow covering the rocky shore then melting, the light steely or more generously glowing. For The T Project, American artists Sarah Banasiak and Alexia Mellor rode the subways during the course of the so-called work day from 9 am to 5 pm, one of them typing memos on an old fashioned typewriter. Much of the amusement of the video rests in observing the reactions of the other people. Rachelle Beaudoin’s Eyelash Extensions is a prime example of a private performance that’s just slightly off-kilter from ordinary life. In it, we find Beaudoin using tweezers to glue lengths of her hair to the tips of her eyelashes, with predictably goofy results. Myk Henry’s Time Out, on the other hand, is a purely public performance, one that of course could never take place in a gallery at all. For Time Out, Henry stops a streetcar in the middle of rush hour in Geneva by tripping and spilling a whole shopping bag full of pasta. He picks up his groceries as slowly as possible, literally crawling under the streetcar to get every last piece. In the meantime, the streetcar driver and its passengers are becoming increasingly agitated at being made late. Henry steadfastly remains in front of the streetcar, occasionally crawling back under it to look for more lost groceries, arguing with the driver, with the jeering passengers, with angry people in the massive traffic jam he has caused, with outraged passers-by. He does this for approximately three minutes (this performances clocks in at exactly 3:01) then desists, letting the relentless flow of city traffic resume. Henry’s piece sharply underscores the inflated and accelerated speed of urban time. It is remarkable how much disruption Henry’s performance at least looks like it caused—and it only took three minutes. Was anyone actually going anywhere that was all that important?

One of the finest pieces in the d2d.5 screening was the beautiful and enigmatic How to Feed a Piano, a kind of tribute to Fluxus composer Lamonte Young’s “Compositions 1960s” by Canadian artists Candice Hopkins and David Khang. It opens with a grand piano set atop a wooden platform, Khang shoveling hay into the piano while Hopkins plays, the notes muted, skittish, and erratic. Eventually Khang himself crawls into the piano, presumably manipulating its strings. Later the lower part of the platform on which the piano is set is opened to reveal a full-grown work horse. Khang is off to the side, privately meditating. He is then covered with blue paint, attached to the horse like a plow, and dragged over the floor, creating long, swishing blue streaks, in a clear allusion to Yves Klein’s body painting performances of the 1960s. (Unlike Hopkins’s and Khang’s, Klein’s performances were intensely ironical fashion statements—there was a small orchestra playing, the performers were beautiful young women, the blue, of course, perfect Klein blue). Swedish performers Elin Lundgren and Petter Pettersson’s Turkey’s Nest involved the artists wearing a big wolf’s head and a bear’s head respectively. Lundgren, decked out in a summer dress and high heels (wolves are fashionable and sexy, after all), dances to imaginary music, while Pettersson laboriously moves bread rolls from one huge pile to another. Sophia New’s uncanny When no one was looking I snuck backstage is close to being abstract. A jump rope with blue, then red, then white light projected onto it loops against a black background, its whooping sounds loud, the jumper invisible. Occasionally the rope falters, as though becoming entangled in someone’s feet; occasionally the silhouette of the person jumping rope flashes onto the rope as though from a distance.

Tehching Hsieh’s epic performances raised the question of what counts as a performance and pushed the relationship between art and existence to its limit. This year’s Éminence Grise Michael Fernandes’s series of performances outside of the Toronto Free Gallery in and around Lansdowne and Bloor raised similar questions, but in a more intimate, one might even say lyrical mode. Unlike in the karen spencer episode reported on in the previous blog, this time I actually knew what Fernandes looks like when I showed up at Bloor and Lansdowne yesterday afternoon—lanky, and with a long, sinuous face and long grey hair, bald at the top. I saw him cross Bloor and head up the street carrying a blue bag.

I figured he would be back, so I brought a cup of coffee and settling in at the street corner and waited. A pair of African men bantered with each other in French outside of their barbershop. A crack addict in an oversized sweatshirt sped furiously back and forth in front of me. Women pushed huge strollers along the sidewalk. Occasionally someone stumbled out of one of the cafés where one can drink cheap beer and stare at ancient television sets all day. Eventually, I grew bored and walked up the street and found Fernandes nursing a cup of coffee in a bakery. Not wanting to disturb him, I retreated to the bus stop to wait and see what happened. School was out and mobs of high school age kids spilled up out of the subway, the boys in their cheap baggy jeans and knock off sneakers shouting slogans at each other and smacking each other’s backs, the girls elaborately made up as though exiting the velvet rope of a nightclub staring at their cell phones with withering contempt. One girl kept shouting over and over into her phone, “I am not a slut, I am not a slut, I am not a slut, bitch, I am not a slut…” Eventually Fernandes left the bakery and crossed the street, and I thought, now something is going to happen! He entered a convenience store; I continued to wait. At some point a young OCAD student, apparently directed to me by a representative of 7a*11d, approached me (I was standing in the shelter at the top of the subway stairs) and asked, “Do you know where Michael Fernandes’ performance is?,” and I said “He’s over in that convenience store, maybe he’s doing something there!” So we walked over to the convenience store, and, inevitably, he had disappeared. Later, it struck me that virtually anything he did might have counted as the performance: sitting in the coffee shop, crossing the street, going into a convenience store, disappearing. And of course my looking for him might have been part of the performance too.

I am not sure Fernandes ever actually “did” or “performed” everything, and the more I searched for a performance or an action, the less I really understood what such things are.

Thursday evening at Xpace featured five powerful examples of performance art, all of them symbolically potent, and all of them exploiting the visceral immediacy of being present to something live and which will, in my view, always give live performance qualities unavailable in documentation. (Even live absence can be weirdly visceral: in Chris Burden’s piece of the late 1970s when he holed himself up in a construction with monitors attached to his hard, his presence was electric).

For her performance, Chuyia Chia appeared dressed in white, a larger rectangle of paper hanging from the ceiling at the end of the stage, a metal bowl, a blender, a knife, a bottle of oil, and a Styrofoam box on the floor. She ceremoniously washed her hands, put on a pair of gloves and a plastic butcher’s cap. From the Styrofoam box she took a whole fish, long and blue finned, and, caressing it lovingly, she cradled it like a baby, carrying it around and presenting it to the audience. She then placed it below the hanging sheet of paper and packed its sides with ice. She then took the bottle of oil and squirted it at the paper, creating a stained, bleeding drawing that itself resembled an ornamental fish. Next, Chia set to gutting the large fish, first placing its viscera into the blender, then chunks of the fish, grinding it bones and all into a puree. Using her hands, she shoveled the puree into the metal bowl, carrying handfuls of the ground fish around for the audience to smell. As anyone who has spent any time in fish markets or the docks in fishing villages knows, fish have a peculiarly potent and to some sickening smell, and this is smell is released with even greater intensity when it is ground up, but it is also fascinating: it is a smell that makes one think of the deep, liquefied, unformed, raw inside of living things. Some in the audience covered their noses; others looked like they were about to gag; others inhaled with gusto. Chia then began hurling handfuls of the fish at the paper, creating an explosive, reeking painting of fish and oil that the audience was invited to join in. Chia’s performance clearly quoted similar performances using animal blood by the Vienna Actionists, but Chia’s performance was not about violence or the expiation of history; it seemed, rather, to involve an affirmation of the unmediated substances of the world, and the way they can be compromised.

Dutch artist Maurice Blok’s performance, on the other hand, was an intricate unbalancing act, a kind of symbolist Buster Keaton routine. On the floor were boards, chairs, a carton of cream, glasses, a bowl, a pitcher, a trash bag full of bouquets of flowers. He began dipping his socked feet in a bowl of water, then taking his socks off and drying his feet. He swallowed cream and dribbled the cream out in a remarkably accurate circle, then placed chairs at the two ends of the circle. Placing a board across the two chairs, he clambering up onto the rickety construction, which looked like it might collapse at any moment, and attempted to pour cream into a glass set below, with little success. He tore open a cardboard box and wore it as a kind of dress; he free fell sideways, thudding onto the ground; he shook flower petals into the audience. In the performance’s final passages, he set a board and blocks of wood up as a kind of teeter-totter with flowers at one end, and sat in a chair at the opposite end. He then tilted back in the chair until he fell, vaulting the flowers up into the air. Blok’s performance was about the delicate relationship between balance and imbalance, between rising and falling, and the cheap, ragged bouquets gave it a kind of clownish exuberance and lyricism.

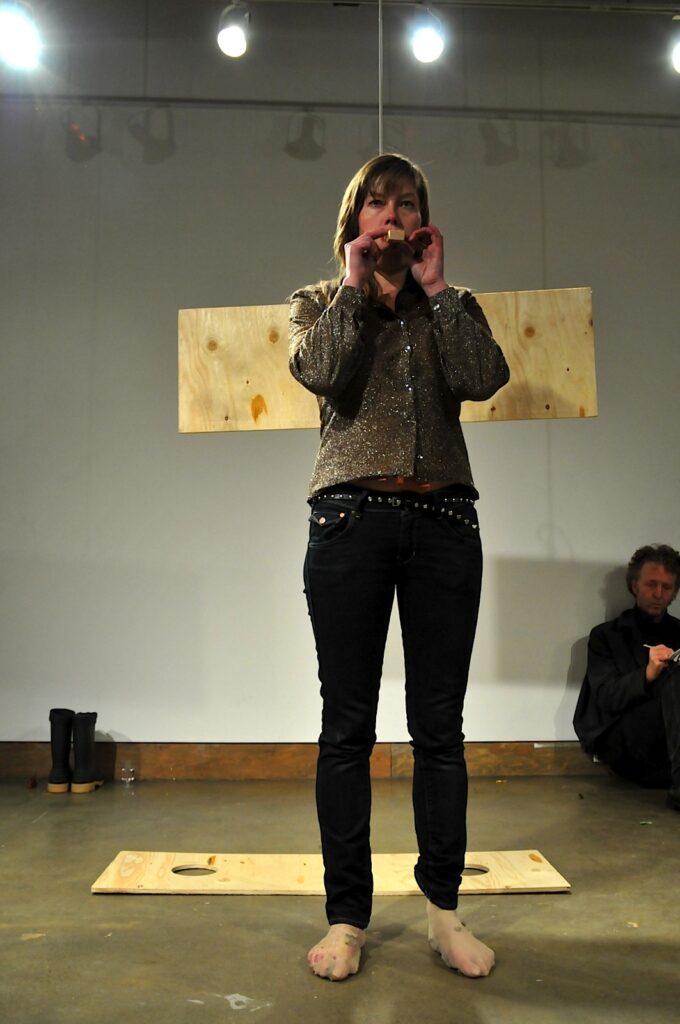

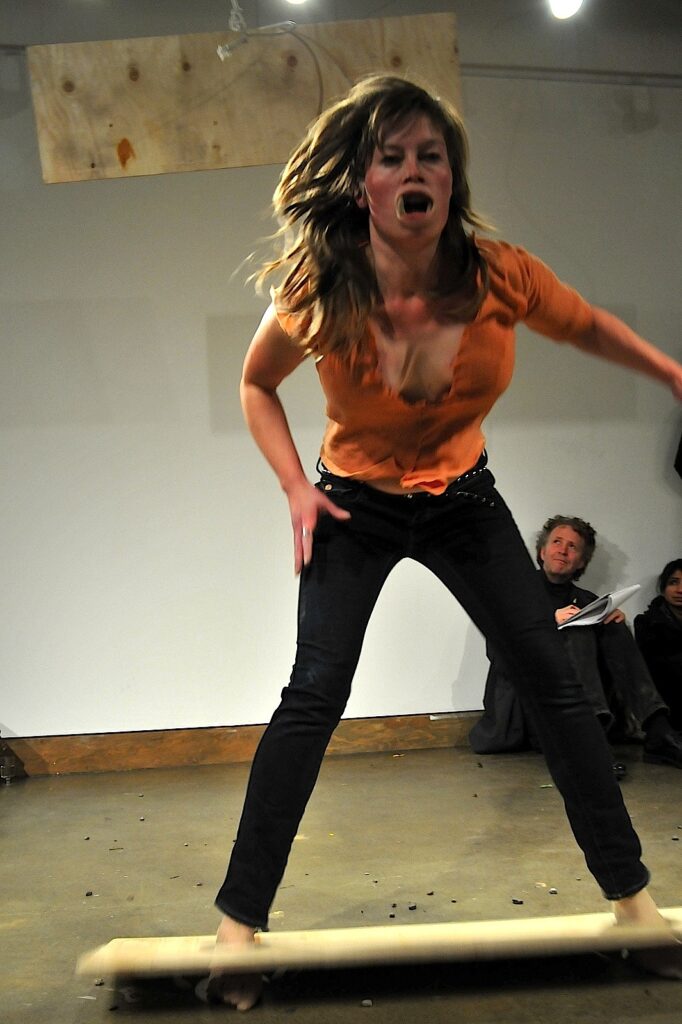

Norwegian artist Agnes Nedregård’s performance, on the other hand, was all intensity. A board hanging on a rope from the ceiling and a board with two holes on the ground, she began by placing a mouthpiece in her mouth that held it open grotesquely, her tongue poking out. A metronome ticked to one side. She blew a whistle. She took her rubber boots off and prowled past the audience in stockings full of dirt and rocks, scowling. She then took her jacket off, revealing an old shirt ripped loose down the front between her breasts. Using needle and thread, she then began sewing the flaps of the shirt to the sides of her breasts and chest. She approached individual audience members, staring at them intensely, then pierced the needle through her skin, pulling the thread tight. She blew the whistle again. The metronome continued to tick. She fit her legs through the holes in the board on the ground, and set herself on the one hanging from the ceiling, gazing, again, with a blank intensity at the audience. Then she suddenly leaped off the board, and it snapped back up toward the ceiling, swinging. The performance ended with her putting her jacket and boots back on and stopping the metronome, whose ticking by then permeated the room. Nedregård’s performance might seem to be about the denial of the body, and of women’s bodies in particular, but it struck me as too physically intimate and present for that; it seemed to me more about the fragility and instability of the body as it exists in time, where time, through the metronome, has become an active, physical, literal part of the performance.

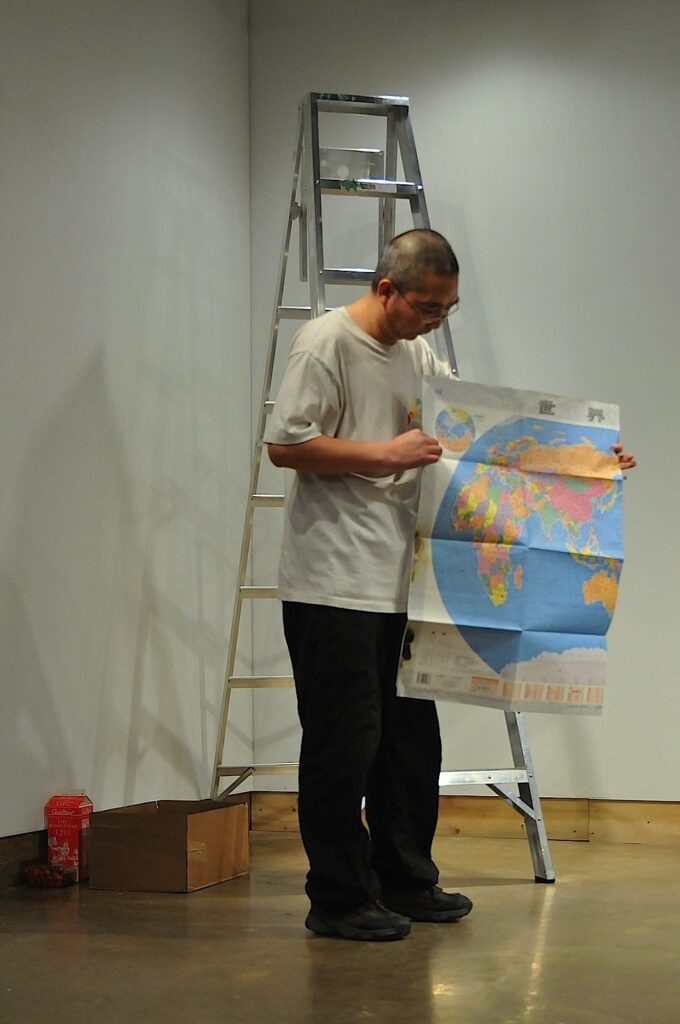

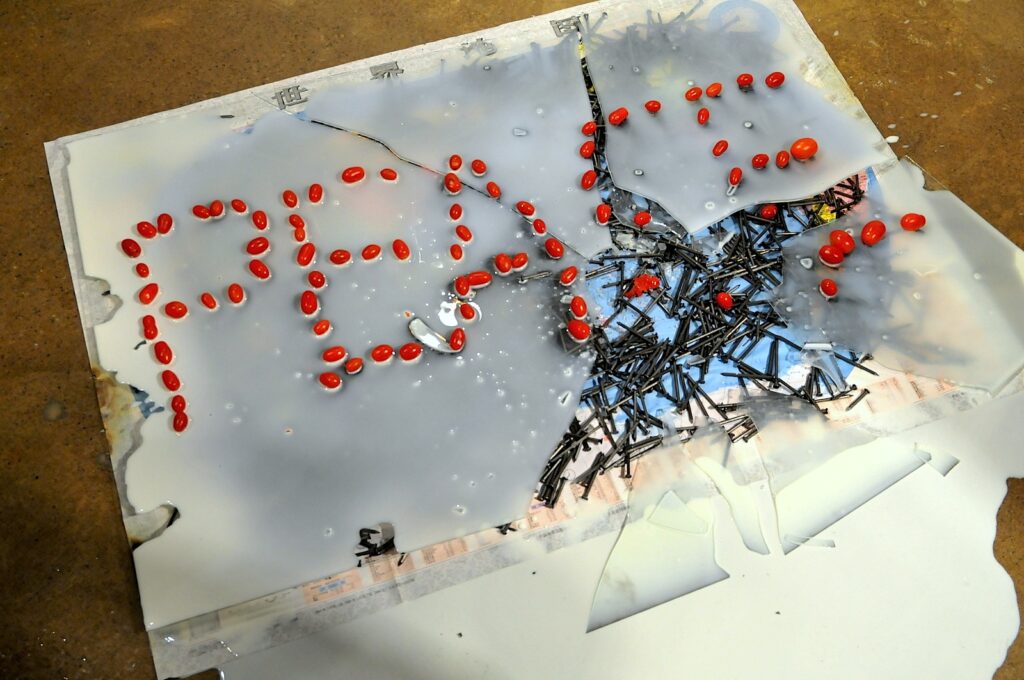

Chinese artist Chen Jin’s performance begins with a standard map of the world—the kind one might find on the wall of a child’s room—spread out on the ground. On his hands and knees, Jin began kissing the countries, the continents, Asia, Africa, North America, Antarctica. Carrying a box of big carpenter’s nails, he climbed up to the top of a ladder and began tossing the nails onto the map, some of the nails settling on the map, others scattering out onto the concrete floor. Once the box was empty, he climbed back down, spread the nails more or less evenly, democratically, over the surface of the map and fit a sheet of glass over it. On top of the sheet of glass he poured milk, the milk flowing out over the edges of the glass, pooling on the floor. At that point he broke open a packet of cherry tomatoes and began arranging them on the top of the milk-covered glass. Shuttling back and forth to check spelling and the shape of letters (Jin’s English is shaky), he gradually arranged them into the shape of a red, somewhat goofy “Peace.” Standing back, Jin looked pleased. With a rubber ball that itself looked like a globe and which glittered and flashed, he bounced the ball and strolled, now gaily, now uneasily, around his construction. And then, without warning, he hurled the ball against the glass, shattering, opening up a kind of wound of milk-spattered nails clotted over the map, the tomatoes rolling everywhere. Jin’s piece is a layered construction, of love, goodwill, violence, and naïvete, reminding us perhaps how fragile and fractal and unpredictable the way we shape the world ultimately is.

Our everyday relationship to time and the world is skittish, fragmented, hurried. The great appeal of monasticism for many, whether it is Buddhist or Christian, is that it both radically simplifies the objects of consciousness and dramatically slows consciousness of time. Performance artists who work with durational pieces are, in a way, the monks of the art world. Tehching Hsieh being perhaps the most rigorous among them. Martine Viale’s durational piece in the basement of XPACE consisted largely of her filling small plastic packets with a few drops of sky-blue ink and arranging them in a gradually expanding rectangle on the concrete floor. The colour itself is strangely beautiful, small, gelatinous. Her face tattooed with lines the same color of blue, Viale went about the task of arranging the packets with a slow, silent, fatalistic precision, as though she were embodying a kind of cosmic necessity. By the second night of her performance, she had expanded her operations, setting up a table for dripping the blue into the little packets. Behind her were curious charts marking the emotional trajectory of her performance.

Sylvie Tourangeau and claudia wittmann’s performance in the rough backroom at The Toronto Free Gallery was not a durational piece per se (though it could have been), but it shared some crucial characteristics with durational works. Pieces like those of, say, Maurice Blok and Chuyia Chia, and Chin Jen, for instance, rely in part on the symbolic resonance of the objects their performances involve as well as on the sequence of actions. The these are hardly narrative works, they are pieces that need to have an ending—we, as viewers or critics, would have a strong sense if they went on too long, or if they ended too early and seemed incomplete. Viale’s piece is so reduced in its elements and iterations that it has no real ending other than an arbitrary physical one; I could easily imagine her going on for days or even weeks, filling up the entire basement with packets of blue, moving on to the basements of neighboring buildings. Tourangeau and wittmann’s performance is one without a natural ending for a different reason: it was driven by relational process activated between the performers themselves as well as the space they were performing in that need not have ever wholly exhausted itself. Sometimes they were on the ground, twisting in parallel contraposition, moaning, birthing, being given birth; other times they tilted against each other in delicate balance; still other times they seemed to have been dropped into a kind of primordial dream space. Normally we think of consciousness as somehow inside of bodies, directing them like the captains of ships, to use Descartes’ famous metaphor from The Meditations on First Philosophy; here they became a kind of corporal consciousness, continuously shifting in relation to one another.