By Daniel Baird

Performance art, as it is currently understood, owes a great deal to the spectacle of ritual, which might be roughly defined as a set of disciplined, symbolic acts that activate meaning within, and to some extent define, a sacred space. One thinks of the role of the Catholic mass in performances from early Tadeuz Kantor events to Diamanda Galas’s gothic rock operas, or the banquet table in Marina Abramović’s earlier work. The allure of the idea of ritual or ceremony in performance is easy enough to understand, because it offers a model of how complex meanings can be enacted, literally and physically in time, without the trimmings of traditional theatricality. But the use of allusions to ritual and ceremony can also be dangerous: it can imbue a work with a false sense of solemnity, an aura of deeper meanings where none necessarily exist.

Two of the works offered thus far at this years 7a*11d are good examples of how a sense of ritual can be used in performance without degenerating into pomposity. In Canadian artist Robin Brass’s October 22 performance Mi Imā Ēkosit, a phrase in the Nahkawe language used to indicate the end of a story, images of young falcons are projected onto the wall. The birds are soft, delicate, quivering, and beautiful. One does not see them flying, but rather they seem to be suspended on the threshold of flight; they exist in a state of pure possibility. Brass approaches the projected image, and, wearing a fringed robe, arms outstretched wing-like, makes a slow, circular movement over it, leaving behind a thick oval of blood-red paint. The image is striking and evocatively ambiguous. On the one hand, the oval blood shape might appear a symbol of doom, as though the performance itself were an elegy to these birds and everything they represent—freedom, flight, open skies, future. But the more I reflected on it, the more it struck me that Brass is making a very different kind of gesture. Brass is interested in intersecting possibilities, trajectories not yet taken, stories not yet told: the red oval does not shut those stories down as they endlessly multiply, but acknowledges and consecrates them. Red is not always the color of death and endings after all; it’s also the color of earthly life.

For his Ringing a Bell in Dialogue, German artist Jürgen Fritz works with Gabe Gaudet, a native drummer and singer who drums and chants while Fritz rings a bell with long, sweeping movements of his arm. The central action of the performance is the repetitive movement of Fritz’s arm, which is both simple and dramatic. The musical sequences follow their own course autonomously, and carry with them their own significations. The bell, for instance, cannot but suggest imminent arrival—of trains, of the hour, of dinner—and the vehemence with which Fritz rings it makes it at times ominous and even frenzied. The chant, by contrast, has a slow, circular inevitability; it sounds as though it has always been there and will always be there. The sonic dialog they create together is one that surges forward in phases. For periods the sharp ringing of the bell seems to recede into the embracing textures of the chant and drum beat; at other periods, the drum beat and chanting drifts behind the more urgent ring of the bell, as though we are hearing it from an increasing distance. Fritz’s soundscape ends up creating a shifting and ephemeral spatial environment in which the competing claims of the sounds intertwine. As with the stories Brass refers to, this isn’t the kind of dynamic that lends itself to definitive resolution; it’s a performance bounded only by the physical endurance of the performers themselves.

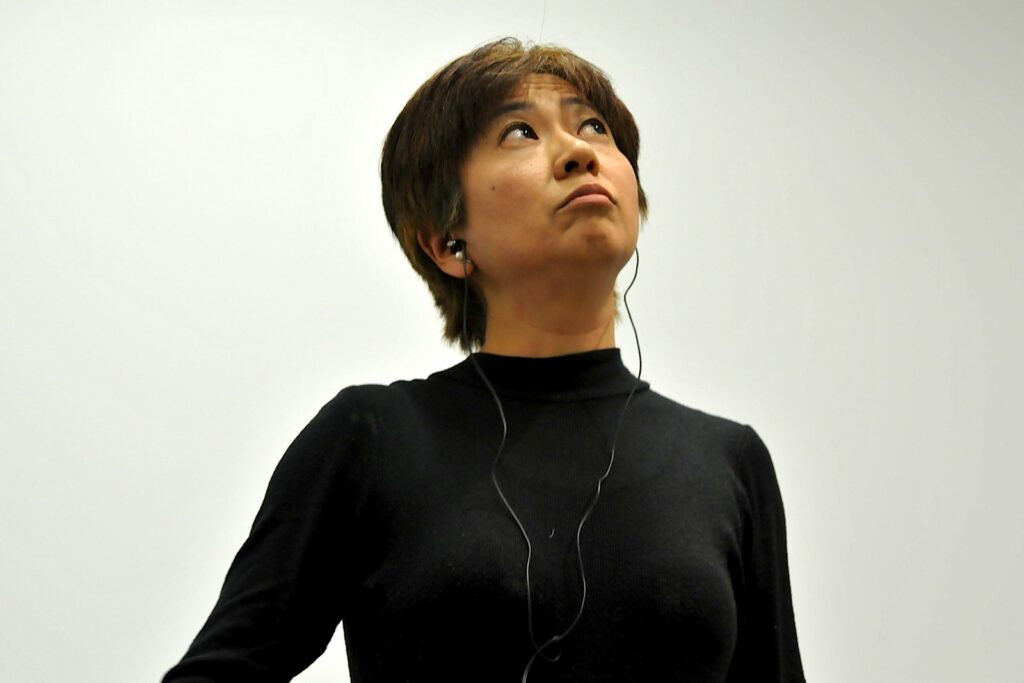

Brass and Fritz’s performances take place within a broadly allusive ceremonial context within which they can be read and experienced. Japanese artist Kaori Haba’s work, by contrast, is domestic and intensely personal. According to Haba, she sets out in her recent performances to create an essay articulating her observations and perceptions using objects rather than words. The ordinary objects Haba uses in her performances—sand, bread, apples, neck ties, a rope—seem to be supercharged with meaning and emotion, as though they had been lifted directly from the unconscious. According to British psychoanalytic theorist Melanie Klein, much of our relationship to the world is mediated by the ways in which we introject objects and parts of objects into our interior world; in Haba’s performance world, those charged, thrumming, ambivalent objects have been spilled out onto the floor.

Haba’s performance style is literal, compulsive, and determined; all of her gestures are at once arbitrary, obsessive, and imbued with a kind of inner necessity. She affixes neckties to the oval of blood Bass made on the wall. She lifts a bag of sand, stabs it open with a trowel, and spreads the sand out on the floor. She eats an apple. She struggles with a long coil of rope. She sweeps and sweeps and sweeps in great circular motions. Now agitated, now calm, now restless and searching, the world circumscribed by Haba’s Women in Peace and War remains relatively contained and balanced compared with the world acted out by Los Angeles-based artist Jamie McMurry in his spectacularly unhinged performance on October 23, Ranchero.

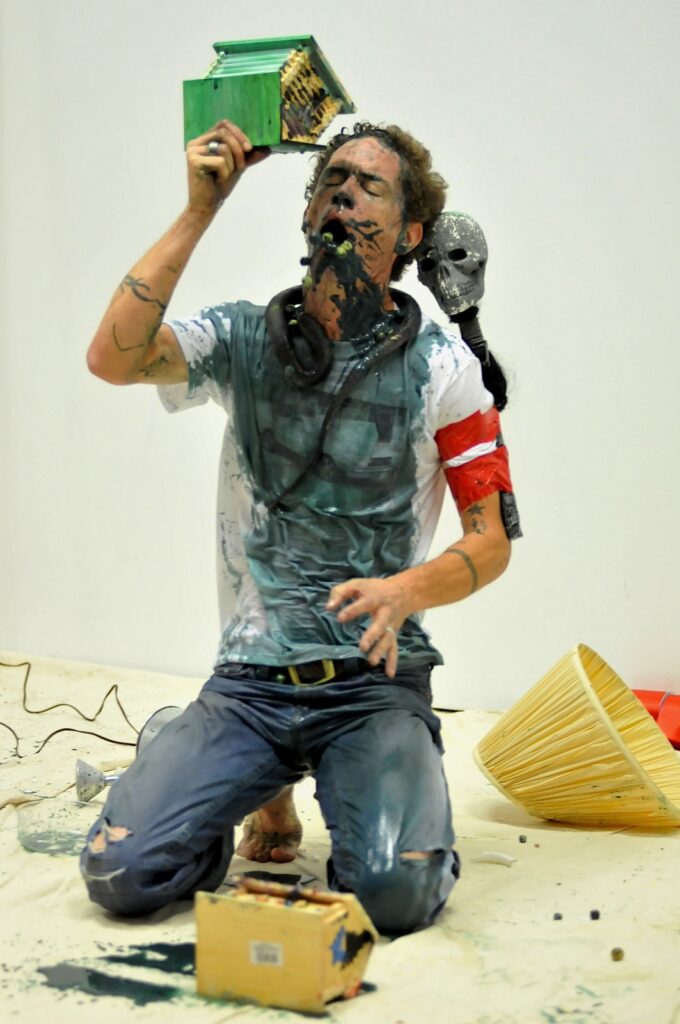

Women in Peace and War is in a way fussy, precise. Like the work of fellow LA performance artist Paul McCarthy, McMurry’s sensibility is epically messy. Ranchero opens with McMurry standing beside a music stand taking a swig of Canadian Club, which he then dribbles from his mouth onto a saucer and proceeds across the space for an encounter with a picture of a Chevrolet Ranchero that is taped to the wall, an image that seems to have a scary, demonic significance for the artist. McMurry’s approach to performance, like that of McCarthy, is intensely physical, expiatory, and raw. He stands at length with his foot in a bucket of ice then attempts to pour the dirty, melted water down his throat. Eventually he fills his shirt with ice, cutting it open and letting the ice spill out onto the floor. The performance becomes increasingly obsessive and even harrowing. He attempts to guzzle whole buckets of paint, physically gagging as the paint spills over his face and naked torso. He attempts to drink an amalgam of paint and pebbles from the model of a house, and then, on the verge of puking, demolishes the house with a bat. At one point he has a kind of shamanic skull rattle taped to his arm as he faces off with the Ranchero with cryptic gestures.

McMurry also asked the audience to participate in the performance, or at least provide additional materials. He photographed a member of the audience and then asked her to take a picture of his ass; he arranged the two developed Polaroids in cheap frames on a kind of alter. He sampled hair from select members of the audience, mixed it with water in a jar, and drank it down. Half naked and soaked through with paint, he pinned a medal to his bare chest, began shearing off his own hair, and recited rock lyrics in a slow, deliberate, deadpan voice: “Cali-for-ni-ay knows how to par-tay…” After another spasm of destruction with a baseball bat, he led the audience out onto the street. Those who had participated earlier got in a mini-van that McMurry immediately doused with more buckets of paint, and then he proceeded to run down the street, waving his baseball bat above his head, as though he were leading a riot.

The night of the performance was cold and rainy, and McMurry didn’t get far before he was pulled over by a patrol car. The police apparently pointed out to him that, when faced with a half-naked, club-wielding man running down the middle of the street in cold rain, someone who looked outwardly insane or at least on drugs, they would be within their rights to simply shoot him. Fortunately that didn’t happen, and McMurry thereafter limited himself to the sidewalk as he wended his way on side streets to a local twenty-four-hour car wash, where a stretch limo and an astonished chauffeur awaited him. Californians know how to par-tay, and a few of those willing to weather the cold rain were treated with a ride in the stretch limo. Those in the mini-van were given loot bags assembled by McMurry’s wife back in California. The performance ended with McMurry getting a proper haircut.

If Brass and Fritz’s performances are anchored by open-ended and public symbols, those of Haba and McMurry are fueled by materializing the dynamics of very private worlds, and they are successful to the extent that they resist becoming wholly insular. In the end it is hard to say what forces McMurry is struggling with over the course of Ranchero, what the Ranchero ultimately represents, why he needs to tie a lamp to rubber tubing, stretch it to its limit, and unleash it against the wall, what exactly he is trying to internalize when he tips buckets of paint into his gaping mouth, what exactly he is destroying when he rips apart a wooden model house, why he needs to festoon himself with lengths of red and white tissue paper. McMurry’s performance was carried by the immediacy of the struggle itself, and the perverse ironies that arise along the way. Perhaps it doesn’t matter that we don’t really know the meaning of most of went on during a performance that lasted well over an hour. After all, most of our struggles are ultimately against forces we cannot identify much less understand.