By Natalie Loveless

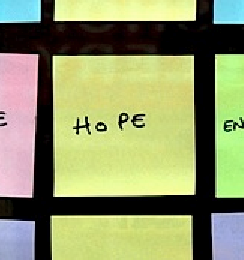

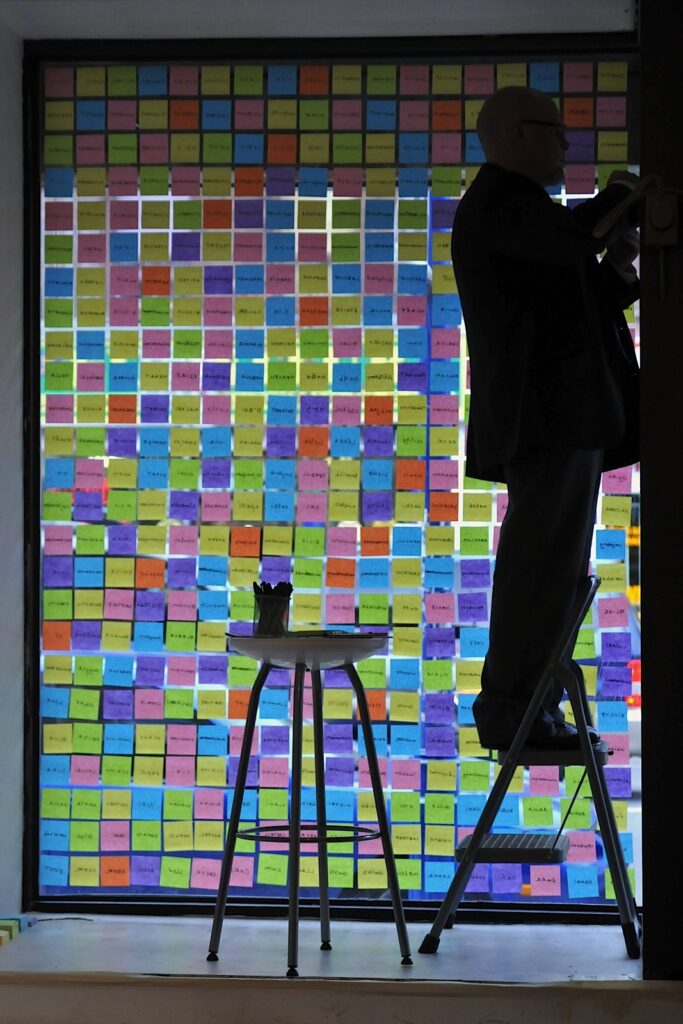

I am walking to Toronto Free Gallery to see the beginning of an eight-hour performance by US artist Jeffery Byrd. It’s 12:30 pm and he is thirty minutes in. As I approach the gallery I first notice a rainbow of pastel Post-Its in the top third of one of the windows, each bearing a single word. As I read them—serene / serenity / mist / golden / cadence / gleam / spacious / pure / ellipse—I see a man through the window’s glare, dressed in a suit and tie, glasses, and dress shoes. His movements are regular, repetitive. He bends over a small stool, picks up a Sharpie, writes one word on each of the differently coloured pads of Stickies and sticks them to the window for us to see. He places them in order, one after the other, a perfect grid of alternating colours.

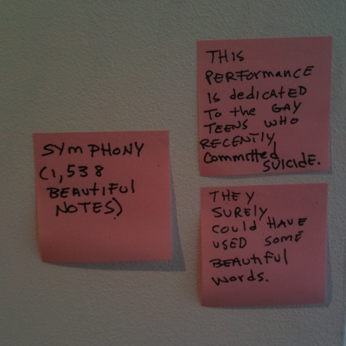

As I follow the words along I notice that German words are interspersed with the English. Asymptote / plethora / leiben / tanzen / caprice / evanescence / weissbier/ milch. What are these words? A response to what he sees out the window? A response to some theme he is working with, one that remains obscure? I step inside and see three pink Post-Its on the wall by where Byrd is performing:

Walking back outside, I let my eyes pass over the words. They crash into each other in a semiotic cacophony: Fantastic Banana Lollipop. Destiny Pumpkin Bubble. Peekaboo Delicacy. Paradox Giggle. Hilarious Moment Extravaganza. Sophisticated Renaissance. Serendipity Twinkle.

…

Six hours later I come back to see how the performance is progressing. By now instead of six rows of Post-Its across one window, there are seventy-seven across four. He is on the last window and has shifted from horizontal to vertical rows, presumably to keep his body visible to the street for as long as possible. There are now words in more than just English and German. I recognize French, Latin and Greek, but there are at least half a dozen other languages. Armed with the knowledge that the performance is called Symphony (1,538 Beautiful Notes) and that it is dedicated to gay youth who have killed themselves, I wonder about this turn to the beautiful word.

The performance is built around a simple gesture. One that is formally beautiful, as the rainbow of pastel spreads and grows across the space. But are the words themselves beautiful? If they are, why are they? Their phonetic resonance? Or do they point to beautiful things—the words’ referents? And, in any case, where did he find this list of words (I find out later that the words come from a variety of sources, including the artist’s personal choice and the Department of Linguistics at the University of Northern Iowa), and why 1,538? Did he test to see that this was the precise number that would fit across the windows? Or does this number have some hidden significance?

I lean back and return to the piece’s formal elegance. Its visual rhythm. I am torn between taking the piece at face value, its simple function as a gift or perhaps a retrospective plea, and following a more complex train of thought. I try to take seriously Byrd’s proposition: They surely could have used some beautiful words. Words. Word. A word. The concept “word.” A signifier. An index. For me, the piece brings together the representational split embedded in all signification with the agony of feeling that there is no place in a heteronormative order for representations of self experienced by gay youth. If we come to know the world through words, then having some beautiful ones on hand can be a powerful thing. I think about the words that I understand as defining me. The words that people have used to describe me at certain moments that, somehow—either through vulnerability or synchronicity—stuck and stay as those words that represent what makes me me.

I am brought out of this reverie by a small alarm that rings to signify the end of Byrd’s day. The gallery is empty—while people have come and gone throughout the day, and spent substantial time with the performance, everyone is now at the Mercer Union Gallery across the street watching the beginning of another performance. His work done, Byrd packs up and goes, leaving me alone surrounded by words. I pick one of my favorites and take it with me: