By Natalie Loveless

A woman enters the space. Sombre, dressed in black. Holds a ball of red ribbon between her cupped hands and bows her head. A moment of solemnity. She then ties a clothesline with the ribbon across the gallery space, a lustrous red line.

This is Irma Optimist, grande dame of Finnish performance art. She is all dressed in black. Black heels, black tights. Black blazer and turtleneck. Stark white hair. She holds up a compact piece of paper, the size of a small boulder, crumpled and roughly painted black. After presenting it to the audience, much as a magician might show his hat for all to see that there is nothing in it, she slowly unfurls it, making gentle crumply sounds, revealing a white plane that emerges from within the three-dimensional black dot. Continuing to work with the sound of the paper—rustling and crinkling—she eventually works it until it is totally open. Not quite flat, she shows it to us as a drawing. A flag—all white with one black dot. She clothes-pins it to the red ribbon. Another ball is presented and unfurled. She repeats the action. This time the dot is a little lower, our attention brought to the variation of small differences.

Repeat again. The unfurled sheets of paper are beautiful, all crumples and shine in the gallery light. She repeats the action seven more times, ten in all, each time presenting the ball and treating us to a soundscape of crumple as we witness the movement of one material—paper—between two states. The pages hang like ink stained laundry. Black on white on white almost completely covering the ribbon’s line of red, which now exists only at the edge.

With this action, Optimist, a trained mathematician, offers us an experience of points in transformation from three to two dimensions. A point, I am told by my authoritative online sources, is not a thing but a place. The point of the point is that it is a total abstraction. It has no length, no width, no breadth: it has no dimension. As if to emphasize this, all ten pages hung, she approaches with scissors and cuts out the black dots, each cut marked by its own crinkly sound in the quiet gallery space.

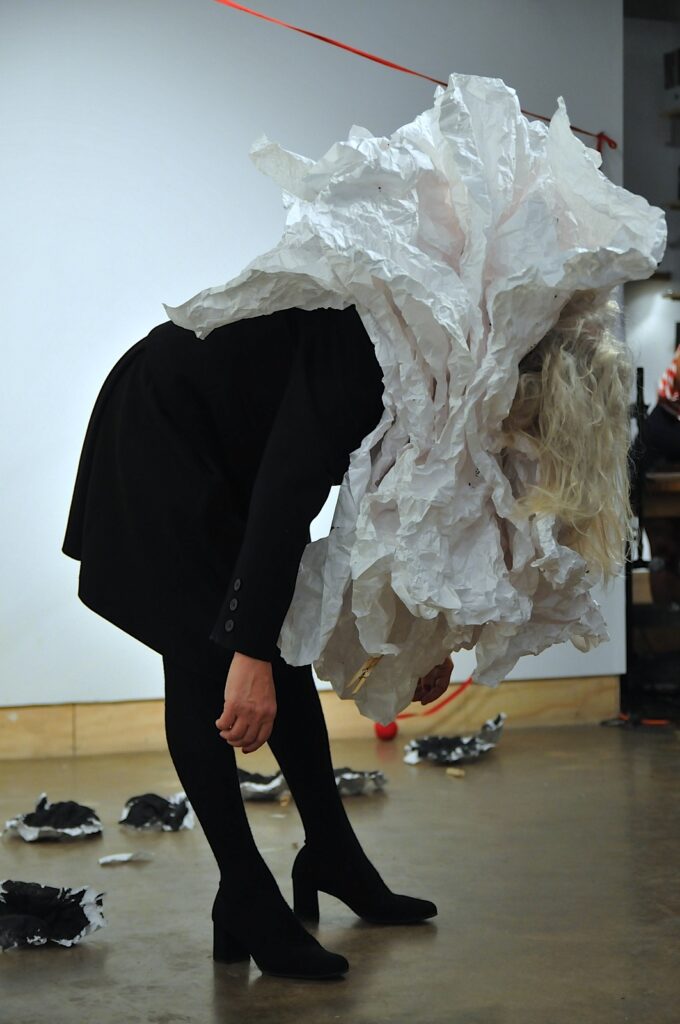

Dropping the centres one by one to the floor, we are presented with ten hanging voids. Then Optimist hides the scissors in her skirt and pulls each sheet down with a firm tug that sends the clothespins flying. When she is done she places them, one by one, around her neck—a seventeenth century ruffle grown to comic proportions.

The clarity of each image Optimist offers is striking, the subtlety of detail and the time allotted to each action in perfect balance. The last sheet in place, she bends at the waist while over a loudspeaker she repeats a single word. I can’t quite make it out. Something like “oit” is repeated at regular intervals with increasing echo. I decide that is it, in fact, Optimist saying point: point point point point. As the word resonates and echos, the separate sounds syncopate and then come together. Once distinct, the repetitions merge in progressively closer and closer articulations until they overlap, become one, and stop. While I am certain that this sounding is in some way conceptually tied to the black dots, I am not sure exactly how. I don’t need to know, however. I am transfixed by the poetry of the gestures. She rises, takes off the sheets one by one, lays them on top of each other on the floor, and bows.