By Daniel Baird

In his incomparable Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga argued, at length and with vast erudition, that the idea of play is at the origins of our idea of thinking. What he meant by “thinking” was not a purely private, introspective process, something done by solitary individuals in their studies or monk’s cells, but rather an experimental process by which we attempt to find some meaningful correspondence between the stream of subjectivity and the stream of reality so-called. Public events in which the social order is temporarily suspended, like carnivale or Halloween, are part of that process. The idea that play might provide not just a relief from the tedium of daily life, but the possibility of radically reformulating how we see the world as well as how we act in it, attracted Situationists like Guy Debord to Huizinga’s writings. Performance art is also a mode of thinking in this sense: an open-ended experiment in how we see ourselves and the world, suspended at the cusp between our subjective and our public selves. For this reason it is appropriate that the final two days of this year’s 7a*11d festival took place on the weekend of Halloween, performers and attendees alike decked out in skin-tight, glittery cat suits, devil horns, rabbit ears, white zombie makeup and the like. It is worthwhile dwelling on what the idea of “experiments in thinking” might really mean. In most of our life, “thinking” implies reasoning something through based on beliefs that we already have, or could easily acquire based on beliefs that we have: we decide that we should get a different cell phone service because another company offers the same thing for less, or that we should go back to school and get a degree as a computer technician because being a freelance writer or a performance artist offers a future of destitution and isolation, or that we should drop everything and follow our new lover to Kamchatka because we value love and freedom and volcanic landscapes over stability and predictability. Or whatever. Experiments in thinking, by contrast, suggest that we are not moving forward based on what we know, but rather opening ourselves to reshaping the way we think.

Sylvie Tourangeau and claudia wittmann’s Friday afternoon performance in the penumbral back room of The Toronto Free Gallery was intensely insular: as an audience, we watched their bodies move, their breaths emerge from their bodies, as though watching a kind of corporeal consciousness ravel back toward its origins. Tourangeau’s solo performance Saturday night, on the other hand, was outwardly directed toward the audience, making the audience literally and figuratively part of the process. Early in the performance, Tourangeau unfurled black, red, and white streamers out into the audience from a glass bowl, asking audience members to hold them taut and aloft so that they served as vector lines linking the audience with the liminal space of the performance. Then she invited selected audience members to come on stage and sit with her, shoulders back, intensely concentrated on the act of sitting. Tourangeau’s piece not only created symbolic physical links between the performance and the audience, but also served as a kind of meditation on the relationship between performing and simply existing in space.

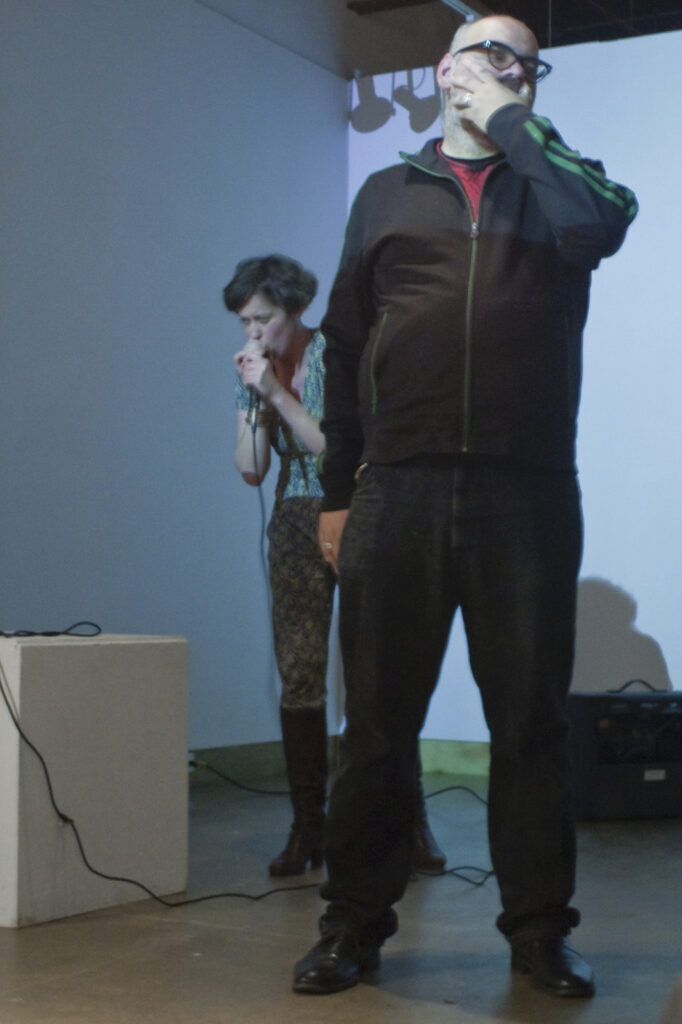

Irish artist Teresa Dillon’s piece, by contrast, was both improvisatory, in the moment, and trace-like. Having invited men over fifty to collaborate with her on a work that combined visuals and music, Dillon and her small entourage had created the performance earlier that morning. Lights dimmed, patterns pulsed on the screen on the back wall. Andrew James Paterson appeared with an electric guitar and began playing a low, repetitive refrain, the other men following with microphones singing ditties reaffirming their desires and life. Dillon meanwhile literally hissed into the microphone, her voice seeming to come from a megaphone in some old revolution. In the end, Dillon’s piece had a slow, beautiful violence to it that got under one’s skin and is ultimately difficult to describe.

Certain modes of performance, I noted in an earlier blog, combine the procedural with the symbolic, the two modes closely intertwined, and the magical piece by Quebec artist Étienne Boulanger falls into that category. Standing in front of a sinister scaffold with a chair set to one side, Boulanger announced that the work that was to follow was “inspired by a nonsense conversation, a dead-end conversation.” He handed glasses of water out to the audience, then sat down in the chair and tilted back until, finally, he crashed backwards. He got back up and set up a kind of teeter-totter, placing a bowl filled with sugar at one end. He looped a rope with a bag at one end through the scaffold and up through the ceiling, holding it tautly aloft. Then, sitting down again, he leaned back, and as he fell backwards again, the scaffold lurched forward, striking the balance and spraying the sugar into the air. The piece’s mechanism had an immaculate and beautiful pointlessness to it, a dangerous trick whose end result was air full of sugar.

Pancho López—whose appearance had been delayed by several days due to visa problems coming from Mexico—arrived late and truculent. He pasted the word “Visa” letter by letter to the front of his shirt. Mexican music playing and replaying in the background, he proceeded to open a case of champagne, shooting each cork into the audience, smirking, as he filled up a huge bunch bowl with champagne, and occasionally taking a swig. When he was finished, he sank the letters into the champagne. Then, suddenly, he grabbed a baseball bat, shattering the bowl, sending a sea of champagne cascading onto the floor.

Julian Higuerey Nuñez’s piece, the conditions of surrender, provided an appropriate coda to the festival. Nuñez had been following the festival all along, sweeping up the spaces after the performances. He took the physical traces of the festival, mixed it into what proved to be a translucent, water-based ink, and wrote on a temporary wall in the gallery: (1) I will go last (on the final performing night), (2) I will sweep (or vacuum) the floors at the end, (3) I will use the collected dust to make a water based ink, (4) I will write, using the ink, the conditions of surrender, (5) this is not to be referred to as performing. Nuñez’s piece was at once self-referential, humble, ruminative, and strangely beautiful.

In Roddy Hunter’s lecture earlier in the week , Notes Toward ‘The Eternal Network’ in the Era of Globalization, he suggested that we may want to give up the term “Performance Art” in favor of “Action Art”; in part because performance art seems to encompass such a vast array of activities and practices, many of which bear little resemblance to “performance” as the term is usually understood, that it is no longer illuminating. I would agree with him as far as such terminological issues go—and there was, of course, a great deal more to his lecture than that—but I also think that some of the most interesting work pushes the boundaries between art and life, art and the world, so hard, that almost no term is appropriate, except perhaps “art.” When Michael Fernandes wandered around Bloor street, or sat in front of an audience laconically reading a peculiar and obscure book about the life of fairies, one was hard pressed to discern the difference between his simply engaging in those activities and presenting a work of art, and indeed the vanishing difference seemed to rest in the activities of trying to make that distinction. And when Tehching Hsieh completed his final, thirteen-year performance, he announced that the work had consisted entirely in living. As this year’s festival amply demonstrated, art in this context is meant to insert itself into the interior of what it means to live here and now.