By Jenn Snider

Kurt Johannessen is at it again. This time he’s ready to play a game: a game about framing, a game about language, a game about experimentation. A game About Thoughts.

“But, this wasn’t a game,” you might say if you were also in attendance last Saturday afternoon to watch Johannessen present his performance lecture About Thoughts to partner the launch of his book by the same name, and indeed you would be right, in a sense. A game is, generally speaking, an interactive activity inclusive of notions of play, rules, and competition. “But, Johannessen didn’t use these conditions,” you might say, and again you would be correct, more or less. However, I’m suggesting the Johannessen’s presentation, which illustrates his ostensive definition for how ‘thought’ behaves, uses a narrative metaphoric visual framework to compose a sort of game with our assumptions.

His talk presents a take on the semiotic and pragmatic properties of a thought. Giving crude visual form to the thought as a something shaped like a droopy kidney bean, Johannessen speaks of little thoughts that grow into slightly larger thoughts, and how they cluster like islands in what he calls ‘thought bags’. That is where they live.

“There are lots of thought bags around,” Johannessen says, explaining that there are areas between the bags too, and that the bags have surfaces which are transparent so that those thoughts at the edge can be seen while others can stay deep inside the bag so that they can be hidden—something like a superficial thought that is apparent versus a sort of hintergedanken or a thought way in the back of your mind, so to speak, that remains unclear.

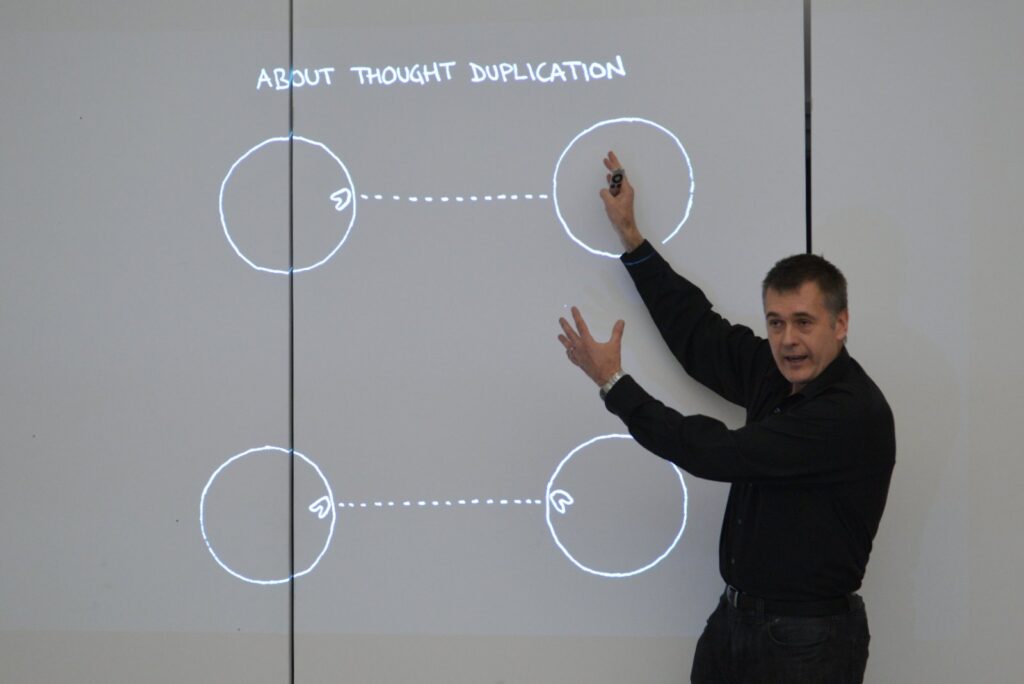

“Thoughts duplicate,” he insists. “After a little while they can migrate if they’re at the surface of the thought bag,” explaining how one thought can move to many bags if they are in the same room, and how thought bags can link up to share thoughts and build them together. There is a limit to this growth though, Johannessen says, called ‘maximum about’, where some thoughts can’t link up to become the same kind.

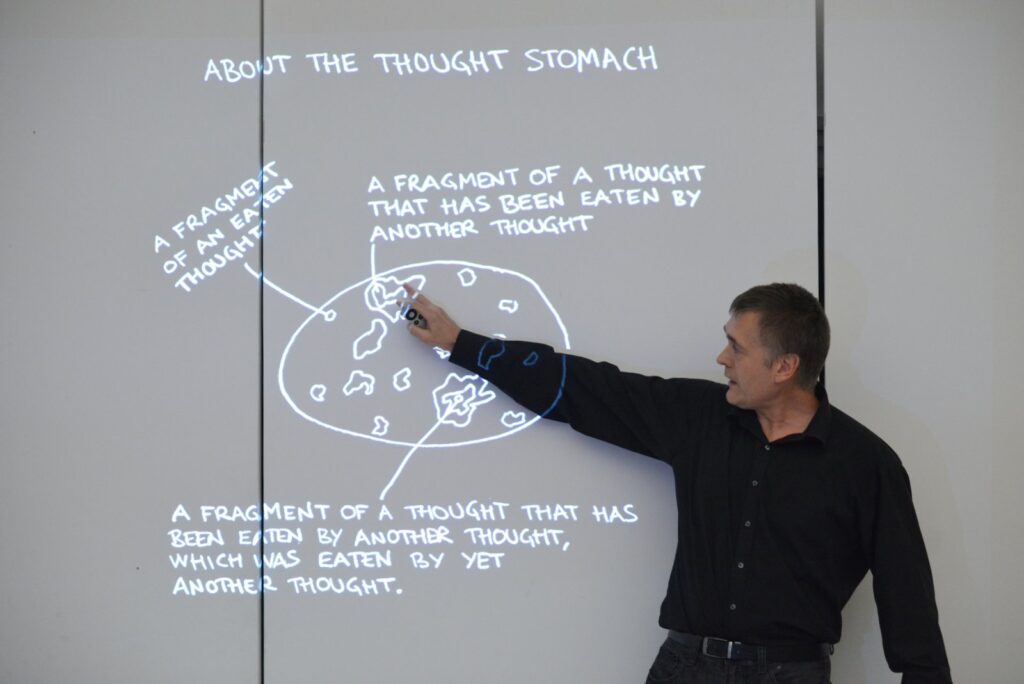

Moving on to the anatomy of the thought, Johannessen indicates on the diagram how the thought has legs, stomach, and knees (which are the most important part since the knees are what allow them to move around, stay flexible, and communicate). Johannessen explains that thoughts have teeth between their legs and that they are cannibalistic. This is normal, he assures us, and is accepted in thought culture.

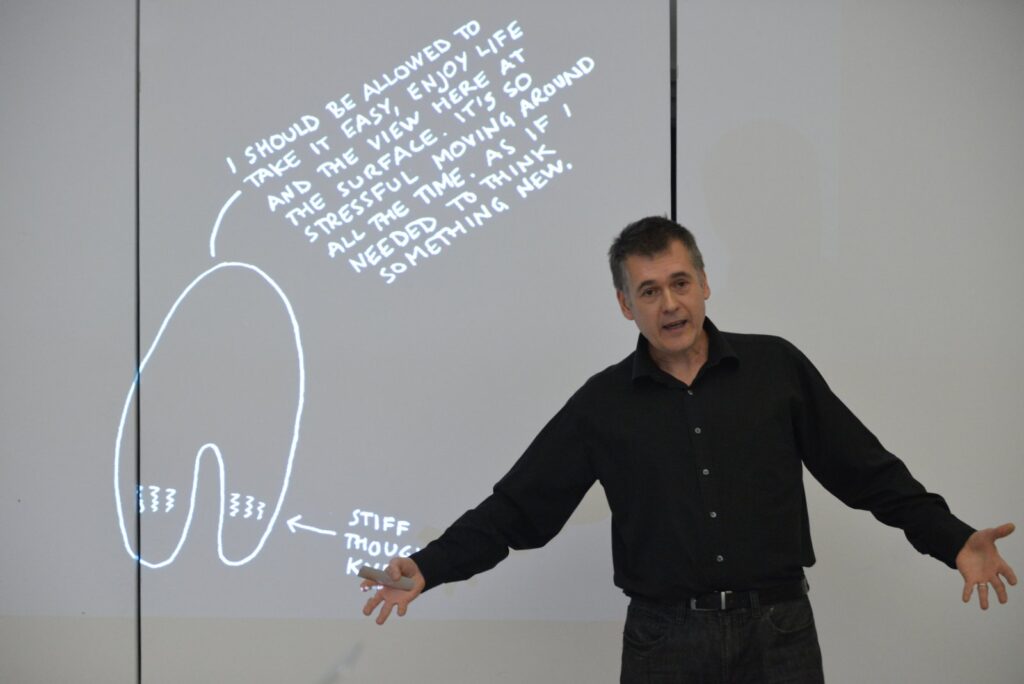

There are stubborn thoughts, which he describes as the thoughts that haven’t been chewed enough which grow inside another thought. Those thoughts in a thought are a mystery to the thought that ate the thoughts, and that those thoughts in the thought can burst out of the thought which is confusing for the thought that ate the thought. The thought didn’t have a thought about the stubbornness of that thought. Once out of the thought, those thoughts will just mingle, hanging with other thoughts, acting as though nothing happened.

Thoughts who have been thinking for a long time grow big, and end up moving less, so they don’t stay flexible. They get slow and develop a disease called ‘Sofa Thought.’ Like a wart, puffy and soft, a sofa thought grows on a thought, is very self-important, and infects the host thought. The host thought starts to only think about resting. The other thoughts start using this thought as a sofa. They lay down on the thought which is a dangerous sign. A thought that lies on the sofa thought can get so comfy it can get absorbed.

Johannessen also describes thought ‘energy theory’ — the energy from other thoughts creates the coming into being thought, causing a thought to just appear. “POOF.” And he outlines his thought about thought ‘historical duplication theory’ — in the thought bag there is an area of the past. In that area, there will be an old thought — and how ‘future duplication theory’ for thoughts takes place is the future space of the thought bag, though this theory has fewer believers, Johannessen says, even though he has “confirmed this is true.”

“Are there any questions?”

Johannessen has shown us a thought-experiment about the definitions of things like thoughts, and it addresses the ways we use context to give meaning to words; a conceptual puzzle to demonstrate how the meaning of a word, such as ‘thoughts’, presupposes our ability to use it in a way that also explains what it is. In this way my use of the term game also lends an interpretative edge to Johannessen’s activity, challenging the use of the word game as he is challenging our conceptions of what we think it means to have a thought.