By Elaine Wong

We return again to XPACE, and there is something new in the gallery window to replace Alejandra Herrera‘s installation. It is a blue ceramic bowl and a pair of brown leather shoes, but they aren’t for use tonight, so I will have to wait to find out what they are for.

When is a rock like an orange?

When Essi Kausalainen performs Untitled (Toronto), a piece constructed of actions and rituals that became images. The colour orange dominated the performance, but not Kausalainen herself, who was noticeably apart from her orange objects (rod, chair, ribbon, orange) in her blue jeans and white shirt. She created several stunning images, such as when she was crawling around the chair, carrying the rock on her back, bearing the weight of the world, as it were. A similar attempt with the orange resulted in disaster as it fell from her back, sending her sprawling. Another beautiful image came when, after taping one end of the ribbon to the pole and the other end to the rock, she rolled up the ribbon before kneeling with the pole upright, allowing the coiled ribbon to unfurl in a slowly widening spiral around her body as the force of gravity on the rock causes it to orbit its pole.

For a moment she sat with the rock on her head, biting into an orange—it seemed as if she was making an homage to Norbert Klassen‘s work on Sunday the 25th. But instead she peeled the orange into a single long spiraling strip, and the visual similarities ended. Once freed, the newly naked orange and the rock were able to change skins, to assume the other’s persona: the rock was nestled into the peel that was reassembled into orange shape, while the orange flesh was wrapped in the ribbon. The matter of the two objects became interchangeable; organic life and stable rock were the same. And yet, when Kausalainen repeated her ritual of action with her new rock and orange, everything was different, yet oddly the same.

She tells me that the piece was inspired by a recent scientific discovery that the first light after the big bang was orange. She asked herself “What do we do with this piece of information that doesn’t seem to make any concrete sense?” And then she drew a connection with performance art: gestures and images that don’t seem to make any sense, any impact on daily life until we stop to realize that it is part of the process that re-imagines the universal and whittles it down to the everyday.

The next performance of the night was Nenad Bogdanovic, who reversed the idea of gesture-as-image into image-as-gesture. Using a canvas suspended at its four corners by four volunteers, he began by painting the word ‘NICER” in bright colours, and then systematically destroyed the image in a series of actions that could have been sponsored by dentists around the world.

At first he ate an apple, then vigorously brushed his teeth, spitting out the water and foam onto the first letter of his painting, N. He repeated this cycle with each subsequent letter, eating a granola bar, then a banana, then drinking a bottle of Coke and finally smoking a cigarette—normal actions undercut by absurdity as he continued to brush his teeth. The canvas became a receptacle for the various tastes and textures in his mouth, while the image displayed and maintained the motion that Bogdanoivic imposed onto it: streaks implied the direction and force of his spitting, and the water pooled in the centre of the canvas, swirling colour together.

Finally, to add to the controlled chaos of the image, he lay on the canvas and performed a series of push-ups in the sodden expanse of paint and water, further rendering the painting abstract and unrecognizable. The artist’s intention behind the piece seemed to be twofold: a statement on how performance and art permeated even the most mundane aspects of his life, but also a willingness to sacrifice the sanctioned in a search for the meaning of art.

Angelika Fojtuch was perhaps preempting Halloween as she began her piece quietly in the small space at the side of the room, positioning herself and her unwitting assistant (whose name we later discover is Thom) in front of a table. Starting at the feet, she slowly wrapped the two of them together, and soon they were forced to hobble over to the front of the room in order to have more space. Thom was left holding the bag of bandages up for Fojtuch’s seemingly disembodied arms as they continue to wrap bandages around the two of them until they formed a hybrid between the Michelin Man and an ancient Egyptian mummy. For the latter half of the wrapping phase, the artist was going entirely by feel as she had wrapped her head in the bandages and, in any case, couldn’t move her body enough to see around her assistant.

The precarious balance of human relationships and co-dependency were inescapable connections for her audience, but it was interesting to note that Fojtuch was doing all the wrapping, continuing to perform this action alone even when it would have been easier for Thom to lend a hand. And this was mirrored in the unwrapping, where Fojtuch waited patiently for Thom to cut through and unwind all the bandages, including those he couldn’t see, before she released her hold on him. Draw from this observation what you will about about human relationships, and who was in control (if either of them) in the process.

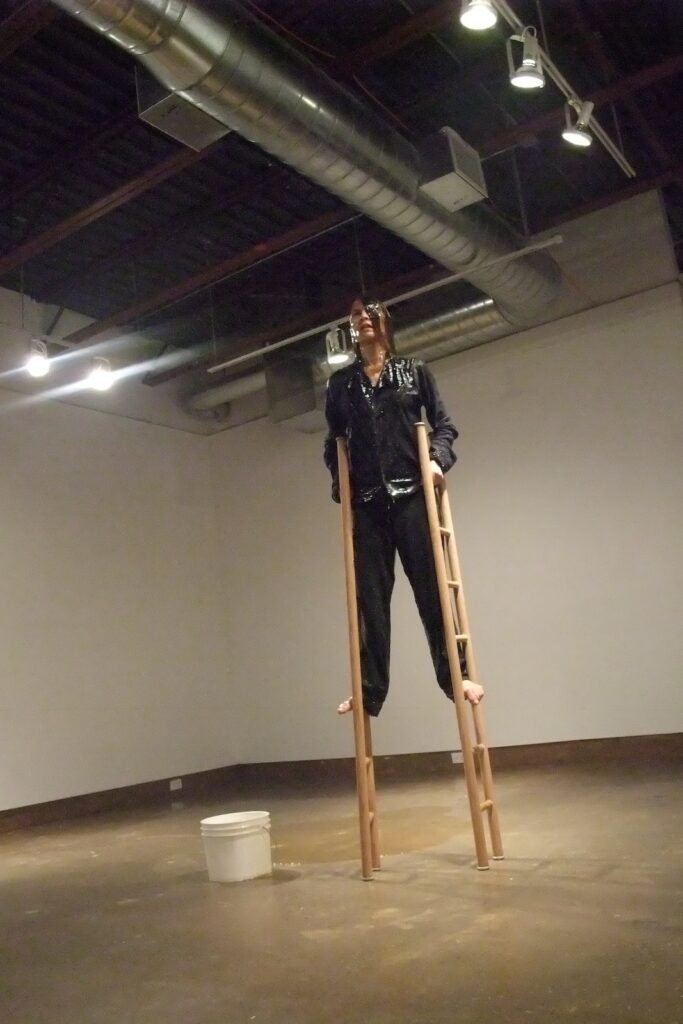

The final performance of the night was a test of strength and will for Éminence Grise Robin Poitras, who performed using honey as a medium. Her first act was to paint a giant X on the wall with the honey, and climb a ladder to embed the honey into her skin. After this, she moved her focus to the centre of the floor where a bucket full of honey and a pair of small ladders lay. She plunged herself into the bucket, letting it spill over and around her, a glorious basking in a substance that took upon the qualities of solidified light.

Like a prehistoric woman emerging from an ageless preservation in amber, Poitras stood in the honey and took up the ladders which she used as a combination of stilts and crutches. Holding her balance steady in a supreme effort of control, the performance became a ritual as she began to move painstakingly around the room, following the course of a spiral in an observance that marked the passage of time, steps of growth and the movement of the sun. Time seemed to have stopped as we watched her progress as, with each quarter circle, she stepped up onto a higher rung of the ladder. The honey slowly spread in pools from her body, embracing the floor and bringing it into the performance as if showing the effort the ground was displaying to hold her up. The scent of the honey, while not overpowering, definitely imbued the room as Poitras came full circle to the X and paid a silent, motionless obeisance before stepping down and time resumed again.