By Andrew James Paterson

I was running early on my route to XPACE, where my intention was to hook up with Gustavo Alvarez and his walking series of public space interventions. With time to spare, I decided to visit Tonik Wojtyra’s Hush My Dear at the west edge of Trinity Bellwoods Park (which I had intended to fit in later). I was able to locate the artist sitting wonderfully still on a rock formation, perched above a visible segment of Garrison Creek which still bubbles underneath much of the park and even nearby civilization. Tonik was dressed properly as a Mountie, holding onto a Canadian goose. He was in character and thus not speaking—he didn’t need to. My first visit to Tonik’s very still performance (so appreciated in the context of much of this festival’s sturm-und-drang-ish body art) was marred only by the overcast skies threatening rain. Upon my later return visit, the neighbourhood had been blessed by a sunny interlude and what was visible was a perfect postcard of Canadiana—nature, clear blue skies, the perfectly-dressed Mountie with his Canadian goose. Postcards are of course constructed as are Canada, Canadiana, Canadians, and also nationalities.

Gustavo Alvarez is one of 7a*11d 2008’s Creative Residents (Norbert Klassen is another among seven), Gustavo has for a long time maintained a belief and interest in taking his performance art outside of museums and galleries, outside of anything that might be perceived as gated art communities. He prefers to break down barriers between artists and citizens. And so he embarked on a series of public actions or perhaps interventions. Actions might be a better word, as intervention can often imply an outsider’s aggression or imposition. Street actions, if they attract attention visually, can gather people and also confuse people. The public is never a homogeneous entity.

Gustavo Alvarez, accompanied by a smallish coterie, set out in a yellow boiler suit characterized by the logo MUSGUS, not the moose and the goose but moss and fungus, perhaps. He carried a birdlike cage with several corn ears dangling as he walked. He also carried an artist’s portfolio, several cases of various weights, and a lot of paraphernalia. At the first major intersection of Ossington and Queen, Alvarez stopped, made himself at home, and announced that he was born in Mexico City on November the first of 1971 and in that place his memories began.

At many more intersections and/or monumental sites, Alvarez would park, set up camp, and create an installation of sorts. All of these installations involved artifacts and objects specifically pertaining to the vocabularies of memory—whether being the analogue videotape tied around the newspaper boxes and bus stop posts at Queen and Ossington, the postcards spread around the bus shelter at Queen and Shaw, the paper trails buried under piles of leaves in Trinity Bellwoods Park, the fresco-like assemblage of little toys built in front of the park’s main gateway, and so on. As he progressed further east on the north side of Queen, he shifted his constructions to the street from the sidewalk. At Queen and Palmerston he created a collage of multiple objects and materials at the side of the street just before the traffic light. He was not installing in a parking space, but he was in a spot where an inconsiderate or just asleep-at-the-wheel driver could make a fatal mistake. Some concerned swerving was indeed taking place. The performer also upped the tension by wildly yelling “Bang Bang!” Public art, or terrorism, or…?

When Alvarez reached the major intersection of Queen and Bathurst, He placed himself in the middle of the street-car track and began assembling the remainder of his belongings on the centre track, directly in front of the stop light and in the middle of the street. A northbound street car brushed safely by the artist, who had staked out a spot from which he could bend his body when necessary. There still was the careless driver risk, and it wasn‘t only the artist‘s coterie who stood concerned on the sidelines. Alvarez began reading rapidly and rabidly in Spanish from a book that he held, and then left the remainder of his belongings in the middle of the street while he crossed back to the northwest corner. Curious and anxious pedestrians were welcome to the souvenirs, or the memories.

After spending more time with the wonderfully calm and sculpturally sensible Tonik Wojtyra, it was time for late afternoon performances at XPACE. The first performer was Martin Renteria from Mexico City. His performance—titled Farewell—began with a minimal set consisting of evenly-matched dangling ropes on the north and south sides of a cubed white plinth of platform. The set remained the focus for several minutes after the performance was declared in progress, and why not? It was a good construction in itself and it set up a very striking entrance. Renteria entered wearing multiple small objects taped to his chest and top body, and also headgear designed from string and tape—his prime materials. A tape note resembling a hair net—that was his headgear.

The performer added and subtracted from the set. He added weights systematically and this maintaining a balance in the context of tension. He cantered his ropes and hung. He selectively removed the tapes and then the taped objects from his chest. He cut the ropes holding the weights slowly and sequentially. He removed the headgear, revealing a gorgeous bald head. Then he bade farewell, knowing that he was memorable. Martin Renteria exuded power while courting danger, and thus held a fascinating attention. I did find myself pondering, as I often do, relationships between performer/audience, top/bottom, bottom/top, and other dangerous binaries. Proscenium and raised performance can be both a placing of spectators in bondage and simultaneously a placing of performing self in bondage. There are codes and there are cues.

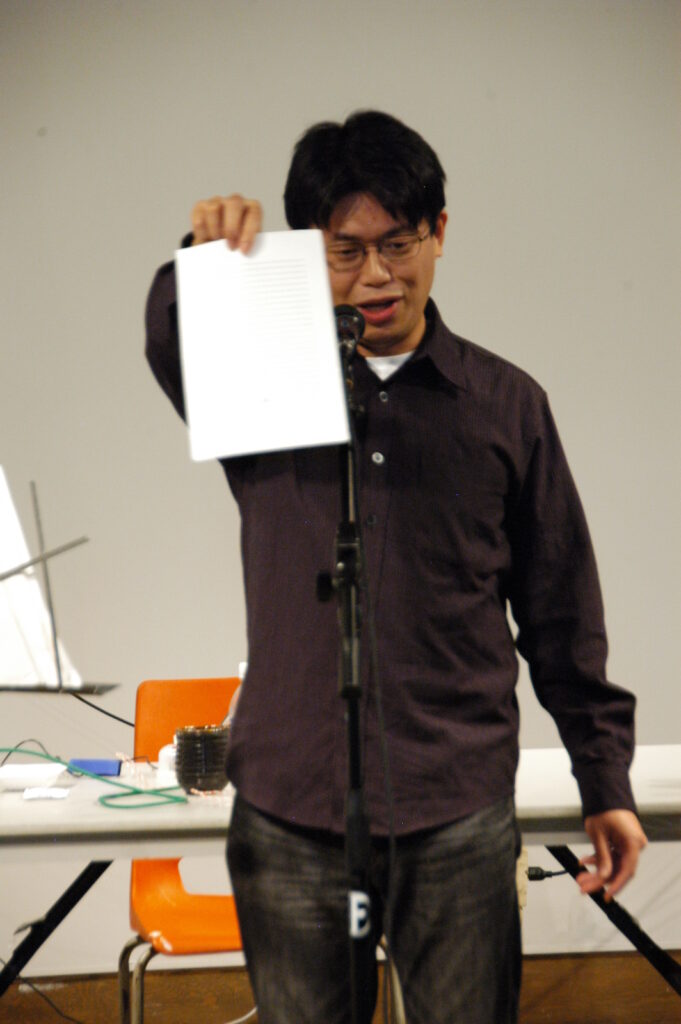

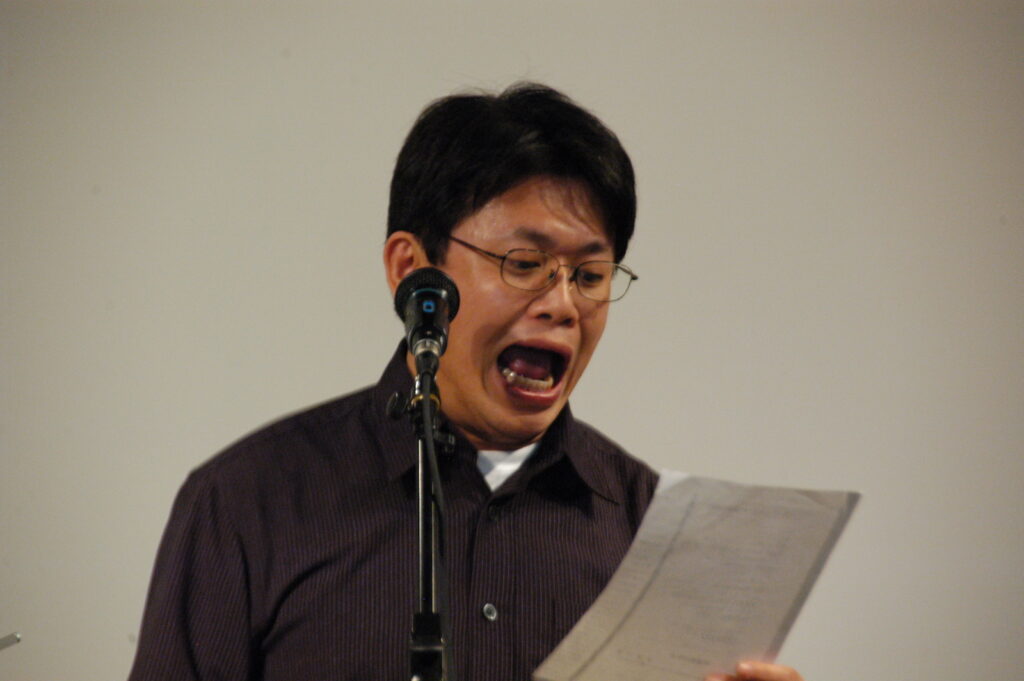

The second upstairs performer (there were none downstairs—too bad) was the Tokyo-based sound poet Tomomi Adachi. He was breathtaking—his breath itself was taking no prisoners and fearing no barriers. Tomomi Adachi divided his performance in two halves. The first half was performed standing, into a microphone with word-sheets on a music stand. A concert recital, and so much more.

Adachi’s recited repertoire included: voice sound poetry form begun with “x,” by Hide Kinoshita; “opus KI,” “opus ME,” “Rain,” all by Seiichi Niikuni, “The Schwitters Variations” (as in Kurt) and “Sekan-no shu,” by Tomoni Adachi, and an improvisation.

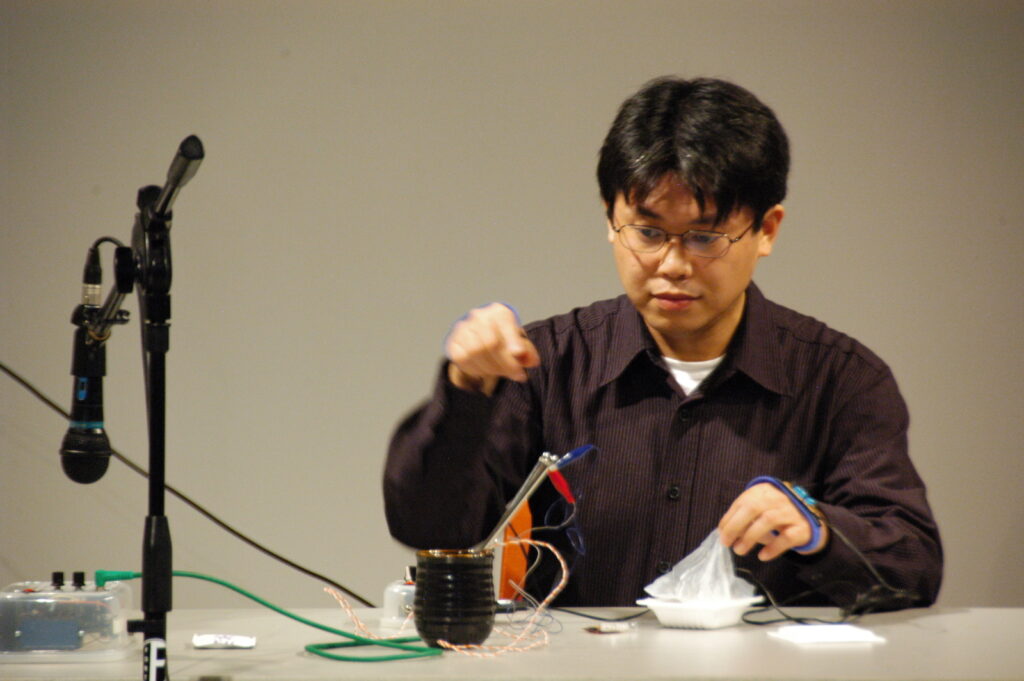

The second half of Tomoni Adachi’s performance was improvised from electronically processed devices and electronically-altered household objects spread across a basic kitchen table. He had eternal delays and permanent reverberations and what-on-earth gizmos, devices that he could turn on and off with his body as well as with his hands. The dynamics were quite extreme, and I did worry about worsening my tinnitus. But the extreme dynamics goes with the territory. If one can’t take the heat, then one should get out of the kitchen. And miss a breathtakingly beautiful excursion into the so rational that it’s delightfully irrational and ecstatic.

The last act—playing and pissing on the notion of “the headliner”—was Toronto-based provocateur, Ulysses Castellanos. Before officially commencing his intended piece (Exercises in Failure Pt.3: Clown Torture Revisited), Castellanos increased the volume considerably from the already high levels of the previous performer. He did so with a twin-neck electric guitar (bass and six-string) and probably some sort of memory/echo device that permitted or excused repetition. He announced his intention to re-enact Bruce Nauman’s Clown Torture while ridiculing the whole notion of himself being one who could do such an re-enactment and also laughing at the entire ides of anything resembling accurate or faithful re-enactments. Ulysses actually displayed considerable flair as a stand-up comedian—he was effectively obnoxious with good timing. Such was not necessarily the right but probably the only tone appropriate for a successful failure. He shut off the monster double-neck, chopped up a pumpkin so he could play pumpkin-head on top of clown, did some amusing monologues about clowns and how they do and don’t scare people, got into costume (confusing arms and legs), and projected two movies onto the wall behind him. One movie was a strobed-out DVD of “The Night of the Living Dead”; the other was a loop from some generic black and white horror movie or whatever. Castallenos jacked up the industrial music drone and re-enacted not only Nauman but possibly Throbbing Gristle as if crossed with shock comedy. It was truly post-ironic, and deafening. Finally, he cut the volume and recited the ridiculous lyrics of “Stairway To Heaven.” Ah, yes. The legacy of the twin-necked and two-headed monster.

As I walked home along the same street that Gustavo Alvarez had performed his series of actions, I saw only scant evidence or traces. His memories had been claimed, or perhaps they now entered into the present tense with their new “owners.” Memories are themselves paper trails—they have a way of losing and then re-finding their home, if not their original owners.