October 26, 2008

By Elaine Wong

During this afternoon’s performances, a great range of styles were presented to performance-seekers in the XPACE gallery as well as along Queen Street and Trinity Bellwoods Park.

Creative resident Gustavo Alvarez Lugo presented the first of his Introspective Actions today, striking out across Queen West and examining, burying and de-possessing his past. Little shrines are all that remain of his passing as he stopped at street corners to commemorate and leave behind those physical manifestations of self.

At the entrance to Trinity Bellwoods park, Tonik Wojtyra‘s Hush My Dear maintained a place at a visual crossroad between peace, charm and parody. In full RCMP regalia, he sat dangling his legs over the edge of a stone wall that overlooked a tiny dribble of a creek. He sat unassumingly, with the quiet competence of an upright law enforcer, carefully cradling a sleeping goose to his chest.

Both mocking and supporting the Dudley Do-Right stereotype of the Mounties, Wojtyra replicated the genuine (if misplaced) desire to do good and pursue it doggedly until the goal is accomplished. Rocking the goose gently, stroking its feathers, and even shushing passersby whose conversations were too loud, he ensured that this Canadian symbol would get its sleep.

By dealing with these specifically Canadian emblems, (and not, say, a soldier cradling a mallard) he has chosen to create a two-dimensional, static image that exists outside our three-dimensional reality, highlighting the fact that in both Canadian geese and the Mounted Police, their currency as symbols have more cultural validity than their currency as wildlife and people. After all, Canadian geese are often thought of as pests and polluters, while the efficacy of the modern RCMP makes very little connection to its red-jacketed, horse-riding past. What Wojtyra presents to us is an image of an image, a parody of a parody, that asks us to judge the value of these symbols on their ability to hold our collective conception of nationality together, rather than to take them at face value.

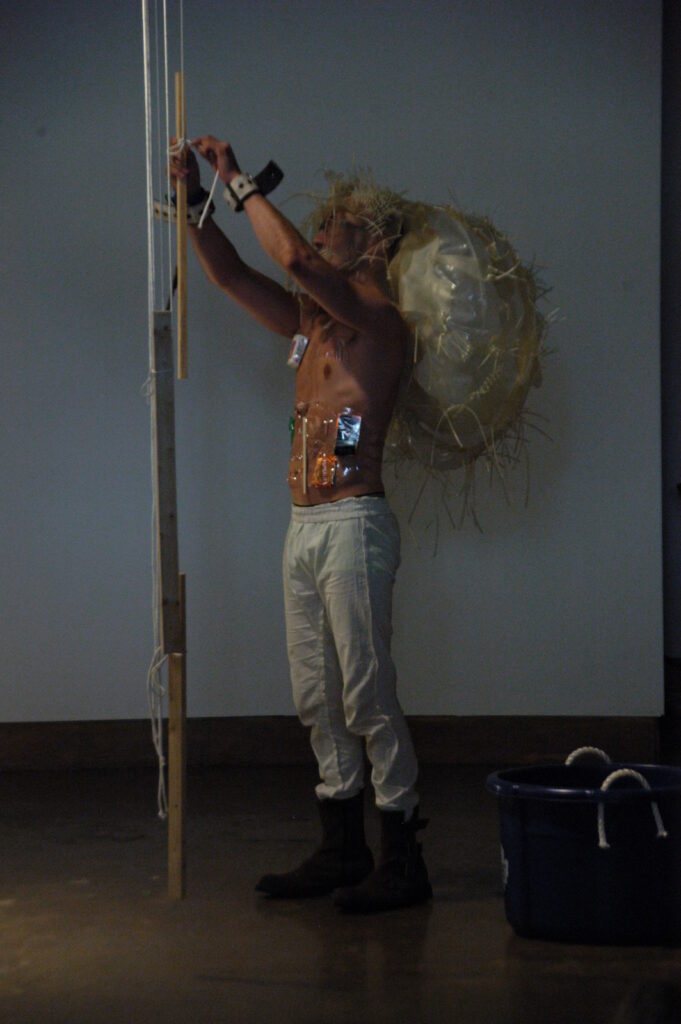

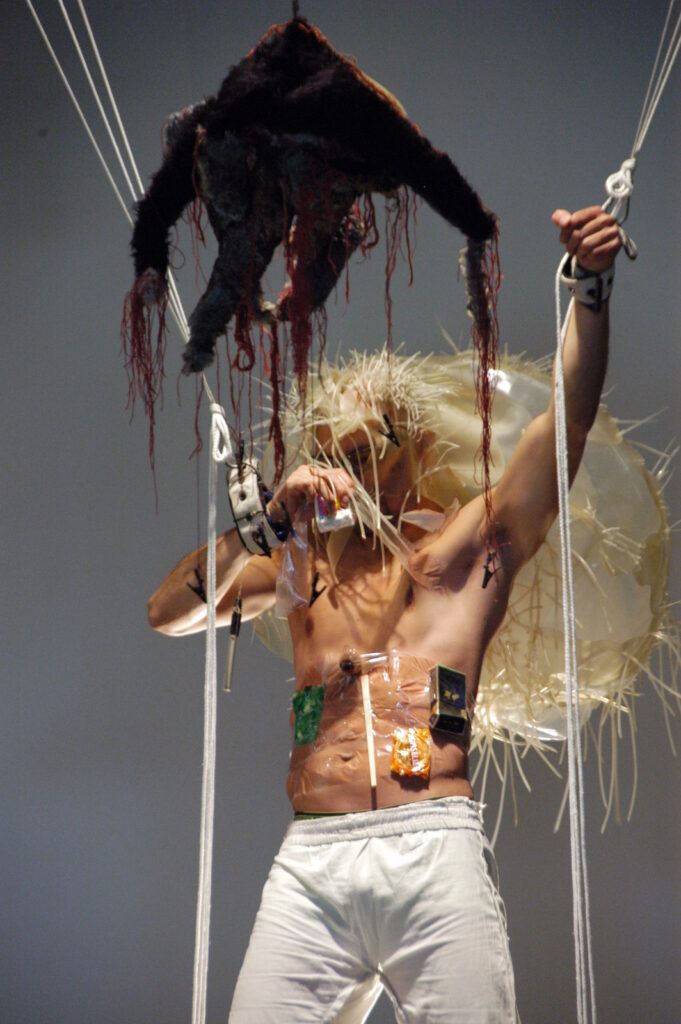

Back in XPACE, the work of Martin Renteria, entitled Farewell, had already caught the eye of the audience. Slung over poles in the ceiling was a series of strings, three on each side of a white wooden dias. Into this visual puzzle Renteria made a dramatic entrance, wearing an assortment of mundane objects taped to his body and a headdress akin to an inflated jellyfish. He affixed weights to the ends of the strings: plastic bags filled with stones, water and clocks (the weight of earth, the weight of time?). From a green suitcase he removed… something, a wool-and-stuffing creature resembling a zombie octopus that he clipped to the ceiling. The dias he would stand upon was harnessed to a bright-eyed toy robot.

Once finished his curious preparations, he began by clipping the other ends of strings to his wrists, an act that transformed into a labourious struggle the relatively simple process of untaping things from his chest and attaching them to the creature.

.If I had seen just a photograph of this piece, it would have read like a visual guide on ‘How to Make Found-Object Art’ But Renteria and his concentration of motion, his distillation of effort, possessed such a strong commanding stage presence that he imbued with tangible triumph a piece that would otherwise be a rather lackluster sculpture-creature. As such, his art takes its value from effort and intention, rather than the individual value of its component parts or the aesthetics of the packaging (a belief about which Paul Couillard was adamant when he refused to sell Norbert Klassen back his artifact box on Friday).

Renteria, finally finished his labour, sliced the ropes one by one and stepped down exultantly from the podium, free at last. He left behind what I understand to be a mobile, one of the whirling, multi-faced toys hung above a child’s crib. A mobile made of labour, of napkins, cigarettes, crackers and ticket stubs. Is this piece a final farewell to the toys and trinkets of a childhood that can no longer pull him forward or protect him from struggling? Or a farewell to the moment, to an intensity of action that can never be exactly replicated again?

After that, Tomomi Adachi added his vocal art to the myriad of strange objects in the gallery. With a microphone and a table full of gadgets, he filled the gallery space with three different elements: sound poetry crafted from his voice alone, improvisational soundscapes created by voice and playback machines, and even the sound of lunch.

The first sound poems were historical recreations of Japan’s first sound poems, including Adachi’s vocalization of a visual concrete poem. As well, we were able to hear some of Adachi’s own compositions, including a set of variations that ranged from operatic solemnity to auctioneer-babble to hyper-onomatopaeia. After this, he created an improvisation for us by using a playback machine that distorted and looped his voice in different ways depending on how it was moved. Using various parts of his body as triggers, he interacted with the device in a fast-paced, cooperative battle between man and machine.

But the tour de force of his presentation, I thought, was his audio lunch. A kettle boiled water, and a package of natto was opened; the boiling water was used to make a cup of tea to accompany the sticky soy mixture. Also set up on the table were a series of electronic transmitters that turned physical stimuli into sound. Using sensors to monitor changes in temperature in the teacup, motion in the chopsticks and pressure in his hands, Adachi was able to make his lunch an aural affair. Though it sounded like a cross between radio static, ground hum and screeching metal, it was fascinating to watch how the slightest movement would result in subtle changes of tone and frequency in the sound.

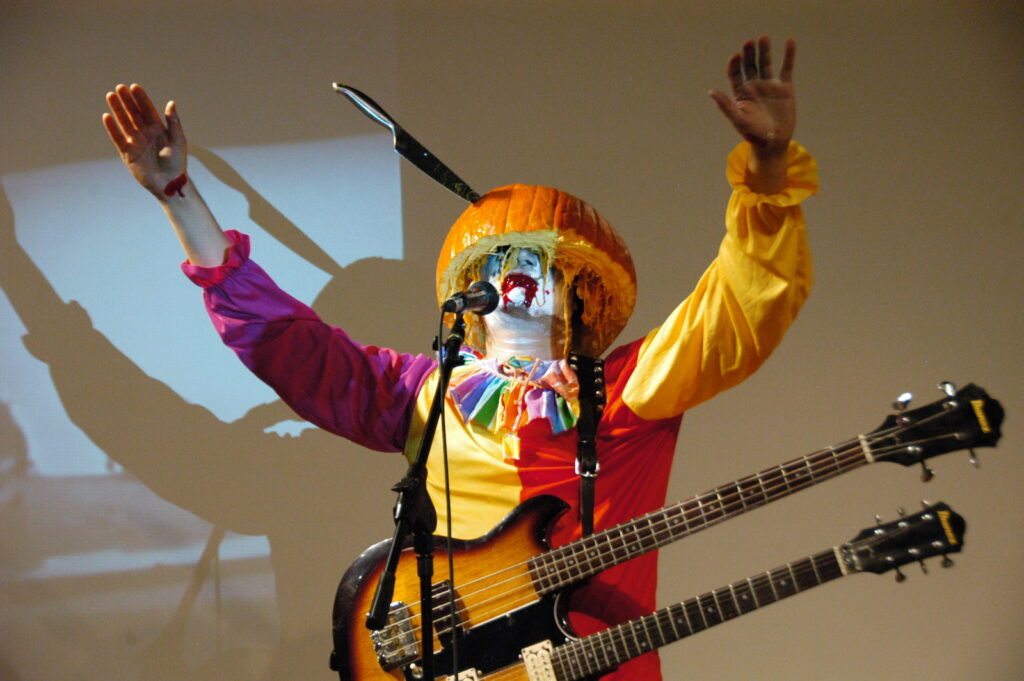

To finish the evening, Ulysses Castellanos played the role of the strung-out rock star to a T. Creating a death-metal pumpkin-clown nightmare that parodied itself, he embraced the underlying campy absurdity of horror and combined it with the campy absurdity of rock stardom. That a clown is a performer, just like the artist himself, was not lost on Castellanos as he took all three personae and debunked them down to their basic level: action.