November 2, 2008

By Elaine Wong

The final day of the festival was wrapped up with a panel discussing terms of engagement: how does one create performance art, and what is the difference between performance art and performative gestures?

The panelists consisted of a series of performers-and-professors: moderator and festival organizer Johanna Householder, Helsinki artist Annette Arlander, festival organizer Paul Couillard, and Governor General Award-winner and festival organizer Tanya Mars. Unfortunately, Tanya’s Skype connection was buggy and we were unable to receive her input into the panel.

The discussion began with broaching terms of engagement: not only what terms we can (and should) use to describe engagement, but also on what terms engagement becomes necessary in the performative world. Annette was invited to provide the opening contexts for the audience, in which she brought up a key facet of defining performance art (versus the performative gesture): in performance art, the distinction between community art (art made for others, with the intention of being seen by others) with body/individual art (art made as a process for the performer) is often blurred. For while an audience is not intrinsically necessary for performance art to be created, or for it to possess meaning (the theatre was presented as an example of this need), neither is performance art an exercise for the artist alone, where the audience can be coincidental (or non-existent) with little ill effect (visual art galleries, for example).

To add to this idea, Annette introduced us to the three cornerstones of spectacle: liminality, contingency, ephemerality. These three qualities of performance are ones we can use to describe liveness and how liveness factors into the blurred boundary that performance art creates. Strategies of harnessing this include: engaging with the site in specific ways that derive their meaning from the environment itself, the encouragement of audience members as active participants, interactivity, generative technology (technology that is flexible and not static—capable of facilitating creation and improvisation), performing open-ended tasks that do not close off potential resolutions, and incorporating accidental audiences, or audience members who do not know that a performance is going on. The idea of audiences as participants raised some questions that we should ask of any performance when trying to understand its liveness: how much of the performance is created in front of an audience, how much with the audience, and how much by the audience?

Annette then emphasized two conflicting halves of performance, and art in general (taken from a Finnish documentary filmmaker whose name I didn’t catch): the problem of encountering reality and the strategizing of representation. How much of a performance is real (“live”) and how much is a representation of reality? (For example, wearing ice skates and a jersey in order to play hockey is a much different idea than wearing ice skates and a jersey in order to present oneself as a hockey player to an observing audience.) This dualism plays out most clearly in the cinematic idea of verisimilitude, that tangles itself up when something that is staged seems to be more realistic than something that is real. (Take, for example, laugh-track artists who rarely use a live audience’s laughter unmodified, as television audiences feel, ironically, that the unmodified laughter is fake.)

This split between mediated and unmediated is particularly salient when discussing the use of documentation, as evidenced by our d2d screening night.

Divisions hover around the use of documentation (archival versus intentional) and the liveness of the art audience within the video—if they, too, are part of the performance, then what marks the audience watching the audience watching the performance?

We were then told an anecdote about how performance artists don’t go see video work and how video artists don’t go see performance work—a fact that, Householder points out, is tied to how performance art demands a commitment of time from its audience, as well as a commitment, period. The level of engagement required to watch a piece of performance art is vastly different than that required to walk through an art gallery, to watch a movie or even to watch a play.

Paul went on to speak about the types of performances that they chose to keep out of this year’s festival. Stressing that performativity does not equal performance, he brought up two examples of performative gestures that he felt were not performance art: John L. Austin’s performative utterance and Judith Butler’s performative identity. Austin’s theory posits that an act of language that changes reality is actually a performance—the words “I do” change one’s status from single to married; a jury’s announcement of “guilty” changes a person into a criminal. And Butler states the daily existence of people, in our myriad of social groups and social identities, is performance. The representation of self through things like clothing, possessions, hobbies, etc.—especially in relation to identity politics—becomes a daily performance that relies on being seen to be valuable. Both of these kinds of performative acts lack what Paul described as “presence”: the essential interaction, the shared element between audience and performer, that he deemed necessary for the festival.

And here, the panel negotiated a key point: If these gestures aren’t performance art, then what is? Paul responded with “that which makes form.” Like Alan Kaprow’s happenings that were no longer a representation of time and space, but rather played with time and space, Paul explained how he as a performance artist is no longer satisfied with being a representation. He described his growing discomfort with creating performances where he is the image/representation and the audience is merely watching, even if they are engaged. He mentioned how the wall of doing something alone, of being the image separate from the audience, is at least negated when doing a performance with someone else. If the audience isn’t actively involved, he is at least performing with intention, to and for someone who is right there in the moment with him.

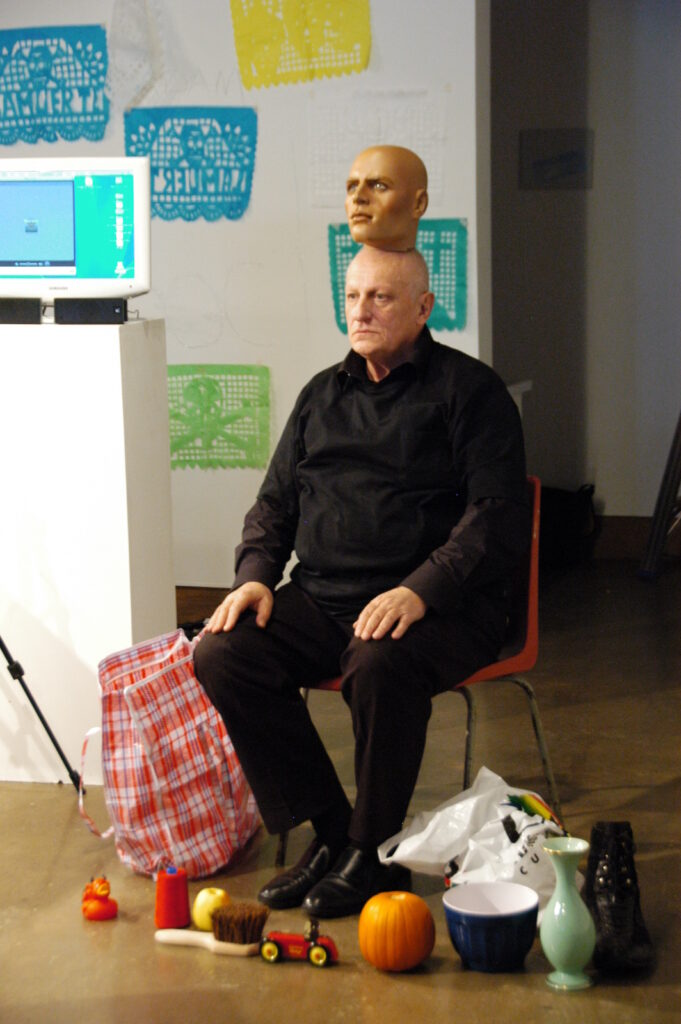

Throughout this portion of the panel, Norbert Klassen performed the final performance of the festival. With slow, deliberate movements he sat in a chair and balanced a series of things on his head. Odd, everyday and bizarre things ranging from a red (devil) plastic duck, to an orange pumpkin, a jade vase, and a white candelabra with white candles which he, of course, lit. Each item had a very strong sense of colour, and his facial expression was perfectly calm as he carefully lifted each item up and down.

Paul went on to create a distinction between performance art and theatre that I understood as the hallmark of the performances in this year’s festival. He described the actor’s craft as one asking the audience to “look at me”—look at my choices, my characterization, look at my skill, look at how well I am being someone else. To this he contrasted the craft of the performance artist, which possesses a shyness, an embarrassment—look not at me, but at what I am doing, look at my actions and the materials around me, look at how my actions are affecting my environment. The performance artist is doing an act for what is created rather than doing it specifically for an audience (which will be brought up again later, regarding performances with no audiences). In this sense, performance art is concerned with what is rather than with representing what is, and the materials become the source of the piece in comparison to the actor being the source of the piece.

A question from the audience challenged Paul: things like the happenings, and Jerzy Grotowski’s theatre laboratories were challenging the idea of mere representation. The example was used of not being Medea as a character, but finding the Medea within the self.

Annette pushed the conversation into a different direction. The focus on presence and live interaction moves towards demarcating theatre in opposition to performance art. What if we were not to start with the idea of presence? If presence is common to both theatre and performance art, what defines performance art? Paul defined this difference by stating that performance art’s role is to question whatever needs to be questioned at the time. It incorporates into its very structure change, flux and virtuousity.

Annette responded with an interesting question. In performance art it is often the artist who is performing, but what happens when we bring up the possibility of “outsourcing” authenticity? Returning, again, to the theatre-versus-performance art division as a source of definition, Annette emphasized how theatre maintains a large division of labour between creator, performer and audience, whereas those boundaries are not as prevalent in performance art. (Which, as a theatre practitioner working in devised theatre, I feel compelled to say is a little bit of an old-fashioned point of view. But that’s a spiel for another day.)

At this point the panel invited Marilyn Arsem for insight into her conceptual piece performed in the XBASE on Saturday night, and how she would feel if another were to perform her piece on her behalf. She responded that she views the performer’s body as a tool for the audience, to stimulate a continued source of engagement with the site. Recalling Paul’s discussion about the materials versus the act, Marilyn’s point of view creates the actor as a material of the site. As such, using “hired help” would not feel the same, since when a performer recreates another’s ideas, they can only portray those intentions they have been told about. As well, outside performers can feel as if they do not have permission to be as improvisational or relational as a piece might require if it is someone else’s piece.

Annette presented the other half of the equation—to think of performance as something not necessarily for an audience is liberating, a fact to which Johanna soundly agreed. A performance without an audience is free to examine and present an action for a reason other than how it affects someone else. Performing then presents an action with a direct meaning that cannot be misinterpreted. Returning to Paul’s earlier sentiments of what types of performance he wanted in the festival, Annette emphasized the difference between artwork and festival artwork. After all, in a public festival meant to draw audiences, why go to the trouble of setting up a performance that the artist doesn’t allow anyone to see?

The nature of festival art became even broader as Paul reminded us that art cannot be made for a single community alone, even if that is the intention of the artist. (Here Johanna challenged his use of the term “communities”; they settled on “audiences”.) Even festival art, created with the intention to reach the audiences that attend the festival (i.e. other artists, press, art supporters), possesses the potential to invoke simultaneous communities. Paul referenced Chaw Ei Thein‘s piece, which resonated with the Burmese community, drawing in a crowd that wouldn’t normally experience this type of festival.

Somewhere in all this discussion, a conclusion was created. The final question that must be asked, I suppose, is whether this very panel constitutes a performance, especially in potentiality, since we missed Tanya Mars Skyping in (with the promise of a Marie Antoinette wig).