By Andrew James Paterson

I begin the longest day of the 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art—the Day of the Dead—out at the Toronto Free Gallery on Bloor just east of Lansdowne. I enter the gallery for the first time since last Tuesday, and Chaw Ei Thein’s mural on the west wall has nearly tripled in both scale and detail. She has left a space slightly past the mural’s centre—a space for what I wonder as I watch the artist print out a text at the top of the mural:

“In this dark and closed space = suffering = getting my body = my body + spirit + possibilities for…..reality? = freedom from Fear = Performance artist = …+…=…+…=…+…= Quiet River”

An audience begins to fill the gallery. This audience is a mixture of 7a*11d staff and guests and people from the neighbourhood, many of whom are of Burmese origin. The audience is directed to the back room of the gallery, where eight lit candles surround a black cardboard box. People cease chattering among themselves in this back room—the box bears more than a slight resemblance to a coffin or perhaps to something gothic. There is an atmosphere of reverence as well as one of dread. At first I think there might be a light source inside the box, but then I realize that the illusion is courtesy of the lit candles.

The audience is still for an extended duration (except for those flashing and documenting et cetera), and so is the box. Then the performer inside the box begins to push leaflets of paper through holes in the south side of the box. This is primarily visible to spectators on that side of the box, and this process goes on for several minutes at least. Chaw now shifts to the east side of the box, and soon audience members begin to pick up the papers and read or look at them. I wonder about the etiquette of this curiosity, yet this section of the performance could be read as referring to methods of smuggling information out of a totalitarian state, or any state without free press and with maximum security/surveillance. After several minutes of this process, Chaw began to push her way through and out of the box and onto the floor. Festival organizers moved the lit candles away as she crawled out of the box and onto the floor, completely covered in a black cloth garment which made vision at best minimal.

Chaw Ei Thein crawled through the front gallery space toward her mural on the west wall. At the foot of the mural, there were several small paint bottles. Chaw dipped her right hand (covered by the cloth or cloak) into the black paint and wrote the letter B in roughly the centre of the white space on her canvas. She found spaces for the letters U, R, M, and A; and then for the words WHAT and NEXT. After she finished this action, some people thought it was the conclusion of the performance and tentatively began clapping. I don’t think this was out of fatigue or certainly not boredom; it was acknowledgment of major achievement. But there was more to Chaw Ei Thein’s performance. She inched her way out from underneath the black garment, slowly donned a Burmese dress and a red scarf, and then indicated the end of her performance. She received richly deserved applause.

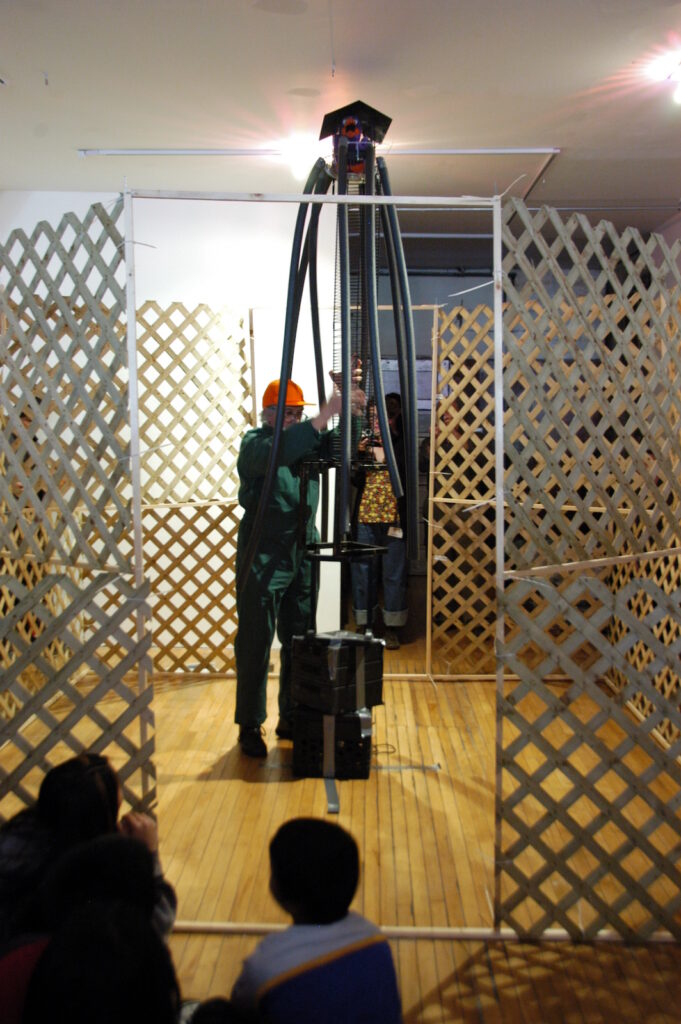

The afternoon’s performance was by Vancouver-based Glenn Lewis, another of the Creative Residents. Two projected documentations of Lewis wearing his green worker’s suit and picking up debris from Toronto’s streets and sidewalks played on the east wall of the main gallery. Lewis set himself up in his Abyssinian gazebo, with its wooden lattice, and began assembling a sculptural object composed of objects he had found, kept, and prioritized. A generic crate served as a base or foundation, a CD and radio set was then placed diagonally on top of the base, a strange-looking ladder came next, and then a birdcage at the top of some eight stringy arms (but with some weird toy with a big open mouth in the cage). An octopus of course came to mind—or some weird monster with tentacles. Lewis then proceeded to scatter five clear bags full of debris in each corner and then in the centre of the gazebo.

After clearing a circular pathway, Lewis danced a “Ring Around the Rosey” and then found audience members to join in the celebration. He had seven inside the gazebo going round and round and round. Then he exited with his followers, and invited anyone who wished to do a round to enter the gazebo and do one. There were no gamers, so the performance came to its natural conclusion. Ring around the Leaning Tower of Octopus?

Shortly after Lewis’s conclusion, it was time to go outside or in front of the gallery. Gustavo Alvarez Lugo had already made a petit installation on the sidewalk, with a small object-holder of sorts, two toy bubble-blowers, and a small but ominous snake figure. The performance artist was wearing his trademark MUSGUS yellow boiler-suit, but today he was favouring a blue wrestling hat. After checking his sidewalk set-up, Gustavo began running on the sidewalk, jumping over his installation. He did this back and forth for a while, eventually for shorter distances until he stopped. Pedestrians walked around the performance and the sidewalk installation. Many stopped and watched. He shouted out SHOKWAME HAS COME. Shokwame is an evil man, a witch, a questionable magician.

He retrieved a black string and wrapped it around an audience member’s lower left leg. He found other semi-consenting observers at four corners from each other and tied them all to his central installation. The Shokwame has come. He caressed his blue wrestling-helmet, then removed it and began to cut it open along the seams. He now had a mask with eyes, nose, and mouth. He added it to the street-sculpture. Now he lay down, blew a few tentative bubbles, again announced that the Shokwame has come, and then concluded the performance. A young bystander/observer asked if he could have the mask. Gustavo declined the request, but informed the boy that he has other masks. This is November 2, the Mexican Day of the Dead.

In the evening, I enter XPACE and observe Sakiko Yamaoka arranging eating and drinking utensils on a long table. She has rows of plastic glasses, Styrofoam cups, cheap wine or juice glasses, and coffee mugs. She is pouring coffee grains into the coffee cups and red wine into the juice glasses. More red wine, I remark to myself. She also poured water into the Styrofoam cups.

A durational performance by Boston-based Marilyn Arsem is in progress downstairs in the dungeon. I eagerly walk downstairs and am impressed by a simple but effective tableau. Overgrown flowers spill over a red clay vase while a woman lies very still on the floor, with long brown hair flowing well on top of her head. A four-note musical motif repeats itself—it is the sound of Chinese wind-chimes and it appears to be activated by a heater. The chimes seem to be singing “Are You Sleeping.” Water very slowly is dripping from the pipes in the ceiling—this is also no accident. I think Gothic, Day of the Dead, and Murder Mystery installations. I plan to return at the first intermission.

In the introduction to Sakiko Yamaoka’s performance, Paul Couillard refers to this artist’s previous site-specific performances during the festival, Best Place to Sleep (Come with Me) and Wind From Sky (Human Beings Are Plants). Sakiko not only coordinated sleep-ins in financial institutions, she “impersonated” a plant in three variety or convenience stores (I regret missing these performances, but my colleague Elaine Wong did witness at least some of them.) The artist held up a statement:

Human beings are alive

Plants are alive

Therefore human beings are plants

Despite wondering how perhaps animals fitted into this equation, I was intrigued by the nonsensically rational premise. I found a strategic viewing position as Sakiko began to move her dessert-sized plates into positions behind the glasses and cups and then press down on the plates. This pressure had the effect of moving the entire arrangement forward, until the plastic glasses began to fall onto the floor. It was quite fascinating to watch Sakiko’s body positions as she arranged the plates into the most effective positions at the back of the table, while more and more plastic glasses were falling and water was beginning to drip from the Styrofoam cups. Soon Styrofoam cups began to fall to the ground. The first landed vertically, but that was only the first. I thought at first she might continue this process until all of the plastic glasses and Styrofoam cups were off the table, but it became apparent that the entire table had to be cleared. Then, since the initial juice glasses did not break upon landing, I thought her pressure might be so delicate as to avoid breakage. I thought that might be one of her intentions. But the falling glasses and the subsequent coffee cups began shattering and shattering, and the water puddle on the floor was joined by wine and coffee beans.

As she approached the final clearance of the table, Sakiko had to lean further and further across that table to push the contents off. I did think of a plant that might be sprawling out of control, or might be dying and losing its shape and its elegance. But this impression was countered by the performer’s need to clear that table, and to press harder in order to do so.

When the table was finally cleared, this was not the end of the performance but rather the end of an initial movement. Next, Sakiko used her body to push the empty table up through the gallery toward the front door, but stopping in front of the admissions desk. After wiping the table clean with paper leaflets, she stood up on the table, with a plastic bag from which she retrieved plastic bags, folded neatly and signed Sakiko Y. 2008. She handed them out to willing members of the audience, who were instructed to shake them and make noise. Sakiko conducted the audience like an orchestra, or perhaps she was playing around with the dynamics of crowd control. Or perhaps this was now the wind from the sky—the shaking sounds from the bags invoked wind and sometimes rain. The audience surrendered to her elements and obeyed her gentle commands—softer, louder, fortissimo, up, down, et cetera, Finally there was a denouement, and the performance was finished.

This was a superbly involving performance. It contained ritual, destruction, reconstruction, and rejuvenation. It may indeed have been analogous to a plant (or animal?) shedding leaves, shedding excess, changing habitats and seasons, and regenerating. Whether or not it can be read allegorically, it was a pleasure to observe, even though I resisted my own temptation to shake.

Since a break was announced, I almost ran downstairs to see where Marilyn Arsem’s performance had evolved to. It was a beautifully calm environment compared to the jostling for positions during Sakiko’s performance, and Marilyn had moved along the string or wire slanted across the east/west axis of the downstairs space. The string attached to the plant had become more visible, and I and others wondered whether she was activating the strings or the strings were pulling her. Her hair was not stretched out as much from her head now, but she was in a static (and seemingly unconscious) position. The chimes continued to ask the performer if she was asleep.

By now Helsinki-based artist Annette Arlander was set up and ready to begin. Arlander had linked two plinths vertically and placed an old birch nest of tuulenpesä onto the plinths. Tuulenpesä are an assemblage of assorted elements—witches brooms, messy conglomerates of branches, all caused by a fungus named Taphrina. Such an assemblage is known as a wind nest, which was the title of Arlander’s performance. Tuulenpesa often grow in birch trees, and Arlander had kept a large wind nest from a birch tree that had been damaged by a storm on Harakka Island in Helsinki, where the artist has a studio. An image of the island’s landscape was projected onto a screen—a shadowy figure was seen against a tree stump from a tree that had also been damaged by this storm.

Arlander’s practice has for some time concentrated on what she calls landscape performance. Not only does an audience see video documentation and found objects idiosyncratic to particular locations with particular natural forces; the artist evokes her own and others’ bodily presence in these specific environments and intends to share that presence. Arlander announced that she would be using a musical landscape/composition titled “Enter The Unexpected,” by Aditi. Then she placed the wind nest assemblage onto her back, handed out headphones to some but not all audience members, and positioned herself in a meditative lookout position in relation to her projection. The headphones were branching out from her body, and some audience members who had chosen to attach them into their ears found themselves being drawn closer to the performer. I chose to remain stationary when I was offered headphones by another audience member, and then I came to realize that I would be missing a key component of the landscape or performance if I did not wear phones. So I did, and I heard the artist’s voice reciting an original poem “Wind nest…place of refuge…” The poem was only a minute’s length; it was meant to be experienced only for that duration and certainly not throughout the entire performance and/or installation. As Arlander remained relatively static in her contemplative position, I became aware of the live wind sounds that were elemental to the artist’s soundscape (in addition to the trance-like music). In comparison to many of the add-a-part improvisational performances of the festival and also many of those performances concerned with pushing bodies to extremities, Arlander’s performance was slow, contemplative, and about listening as much as seeing. It involved and also invoked the so-called lower senses—smell, and touch. Wind Nest – variation nicely counterbalanced Marilyn Arsem’s slowly unraveling spatial performance that was occurring concurrently in the downstairs space.

The final performer of both the evening and the festival was none other than Gustavo “Musgus” Alvarez Lugo himself. This time performing inside a gallery space rather than on the street or in a public location, Gustavo had assembled one of his trademark altar-installations on the floor. He enters banging a drum on its side with a mallet-stick, and he wore a facial mask on the back of his head. He moves toward audience members while banging the drum. Then he walks up to the west gallery wall furthest from the street and writes CHABOCHI on that wall.

The word CHABOCHI loosely translates as outsider, or foreigner, or person outside of polite or acceptable society (suspect-immigrants, suspected terrorists, persons with AIDS, lepers, et cetera). “Chabochi is a concept that the Tarahumanas (indigenous to the region of Chihuahua) use to determine the mestizo, the one that is not like them, who is not of them, the one that is different.” (7a*11d catalogue, 2008, p. 37)

Gustavo lights the contents of a cup which is part of his little shrine or altar, and uses paper to increase the burning. He picks up the cup and transports it over to the wall under his writing, lets the fire extinguish, and asks the audience “Who is Chabochi?” He wants a volunteer—he wants someone else to declare themselves other or outside. He procures willing participants from the audience—Istvan Kantor, Annette Arlander, others. (I let my guard down and volunteer.). Those who admit or declare themselves CHABOCHI are handed plastic flag-papers similar to the ones Gustavo had used in his Museum subway station installation, and instructed to tape them to the gallery wall and write their names on the wall at the top of the papers. When all the volunteers have done so, Gustavo then inverts the dynamics—the balance of his equation. He asserts that there is no Chabochi, that there should be no more Chabochis, and that there is one world. Then he says thank you, and the performance and the performances of the 2008 7a*11d festival are now history.

The Day of the Dead had been observed, and now the Day of the Dead had drawn to its conclusion.