By Natalie Loveless

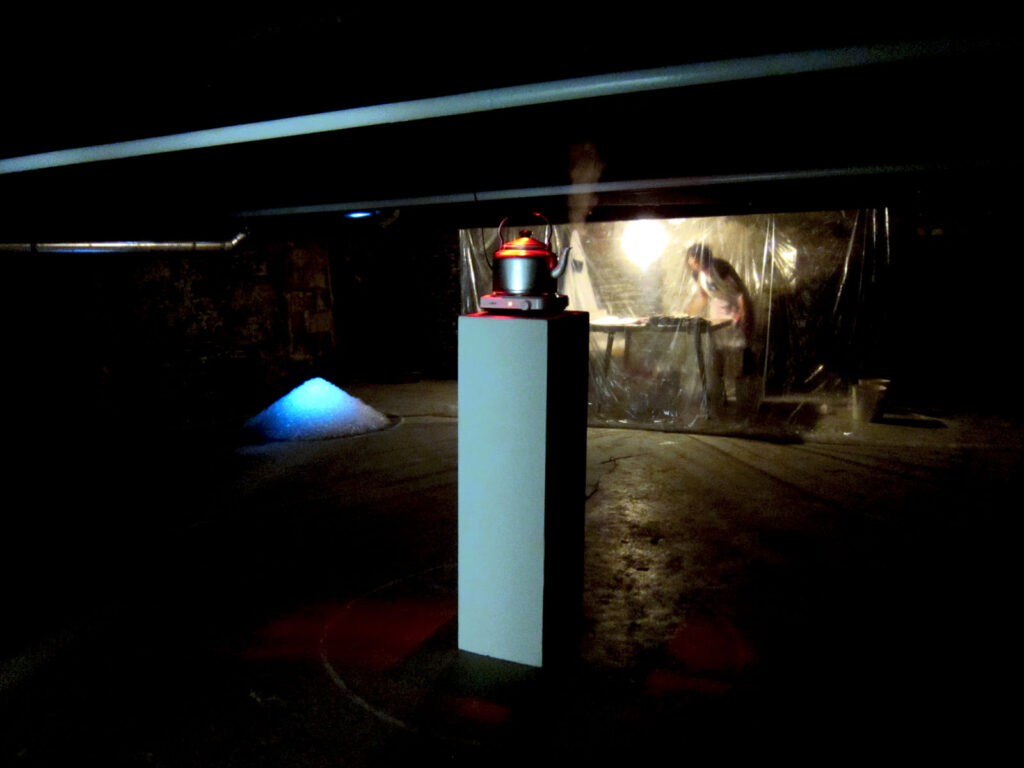

As I head down the stairs to XPACE’s basement area, XBASE, I hear a faint digital soundtrack that manages to entice me and make me uneasy all at once. It is high pitched and rhythmic, like the clicking and beeping of some alien Pygmy music. At the far end of the basement, Berenicci Hershorn stands in a clear plastic enclosure, bright spotlight behind her. The plastic gives the performance a danger-zone feeling. Her smock has a large black decal at the chest, and for the life of me I can’t help thinking that it looks like the headdress of a HAZMAT suit. Whatever is going on behind the plastic is meant to invoke toxicity. Or messiness. Or something dangerous. To my left, as I stand before the plastic enclosure, is a huge mountain of ice piled inside of a large chalk circle. It glistens under a white spotlight like a mound of oversized diamonds. In the center of the space is an old tin kettle, boiling on a plinth and lit by a tiny red LED. It also stands inside of a large chalk circle. We are privy to a ceremony of some sort, but whether it will end in mercy or malice I am not sure.

Hershorn’s action is repetitive. For the duration of the evening she stands behind a long kitchen table wearing a white smock. Methodically, she removes a piece of newspaper from a pile, folds it in preparation, and places it in the center of the table. She then pours a dollop of a red, viscous material (paint?) from a tin watering can into the center of the newspaper and gently folds it into a little packet. Each folded newspaper is a feat of origami. Gently she ties the packet with a piece of twine and places it at the top of the table. In between each action, Hershorn cleans the space. The pile of red liquid packets accumulate as the performance moves from its first into its second into its third into its fourth hour, some seeping through, some retaining their integrity. Fold. Pour. Tie. Place. Clean. These are the five actions that Hershorn repeats and repeats. The steam from the kettle, meanwhile, permeates the space with a faint something—I can’t quite tell what. The smell is soothing, in stark contrast to the sound and the site of Hershorn herself, who I find determinedly unsettling as I inhabit her symbolic universe in its fastidious and unremitting continuity.

Over the course of this five-hour performance, Hershorn invites us to experience something between the production of bio-weapons of mass destruction and a Voodoo high-priestess’ ritual. As her smock becomes smeared with blood-redness, the enormous pile of ice (I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that it is 40 or 50 bags worth) begins running a river of water towards the front of the space. I watch the water in two forms, the ice on the floor and the steam from the kettle, transforming and moving through space. I watch Hershorn making her little tied packets of blood-not-blood, ready to post or send or scatter to whichever corners they are destined for. I watch all of these things to the sound of the electronic alien Pygmies, and leave the space for the final time, as I began: vaguely unnerved.