By Jenn Snider and Alison Cooley

To cap off the 2014 Festival Blog, Alison Cooley proposed that she and I (Jenn Snider) have a conversation about lo bil’s performance The Clearing, which took place all day Saturday November 1st, from 9am until 8pm.

By collaborating on the public archiving of a performance premised on the public sharing of a personal archive, we think this post nicely encapsulates the sort of tensions, exhilarations, and tangential connections we’ve enjoyed while on this epic adventure of textually documenting and discussing performance art. We hope you’ll agree.

A big thank you to the Toronto Performance Art Collective festival organizers, the volunteers, the audiences, the readers of our words, and most especially (and always) the artists.

Okay, here we go…

ALISON COOLEY: Maybe a good place to start would be if we each describe our experience of encountering lo’s piece. We were on day four of a five-day festival and both of us had been spending our time (at the festival and at home and at night and in all of the hours surrounding it) trying to compulsively textually document it. And so at the point when lo started her piece, this whole question of the impossibility of the archive and of being true to the archive really resonated with me and with what we were doing, on a biographical level. I felt so overwhelmed with all of our writing, and in her work she was spreading out all of this writing that she had done over the years or that other people had sent her, and trying to surmount it.

JENN SNIDER: Absolutely. I definitely understand that biographical connection. In lo’s performance, I got the sense that in some ways she was trying to find the narrative, seeking something actively through the day that would bring all this material, this ephemera of her life, into the present moment or into her present experience. In a way, I felt like the task that we were doing (ostensibly documenting the performances) was immediately going to function differently in the context of that performance simply because of the meta-ish nature of archiving a process about an archive.

My first experience of lo’s piece was actually very jarring. Up until then, I had written each blog post by going through a process of locating myself in relation to the experience of the performance and the artist and the space and the audience and so on, and sorting out what I felt and what I thought, and sometimes those were very different things. With The Clearing this immediately changed. Over the course of the first few days of the festival I had been trying to be discrete. I would sit somewhere in the middle of the audience and take notes on my smartphone. I didn’t want to stand out as one of the bloggers— I wanted to blend in as part of the group. As the festival went on though, I felt a little bit more comfortable in the role, and more like “yes, I am the blogger,” but also, it became a matter of efficiency (typing on my phone was very slow), so I started carrying my laptop into the performance space. For the most part I didn’t feel that was out of place, but when I came in to watch lo’s piece, it was different. I sat down with my laptop and instantly felt very seen by her, as though I had declared “I am here to document you.” She spoke directly to me, as I later learned she was doing with other people who came in but I didn’t know that yet. The first thing she said was… well, she was talking to someone else when I came in, but then she turned to me and said, “I keep speaking out to the audience, but I don’t leave the action.” I wrote that down but felt sort of guilty that I had probably confronted her with my intention to record her actions vis-à-vis my obvious laptop.

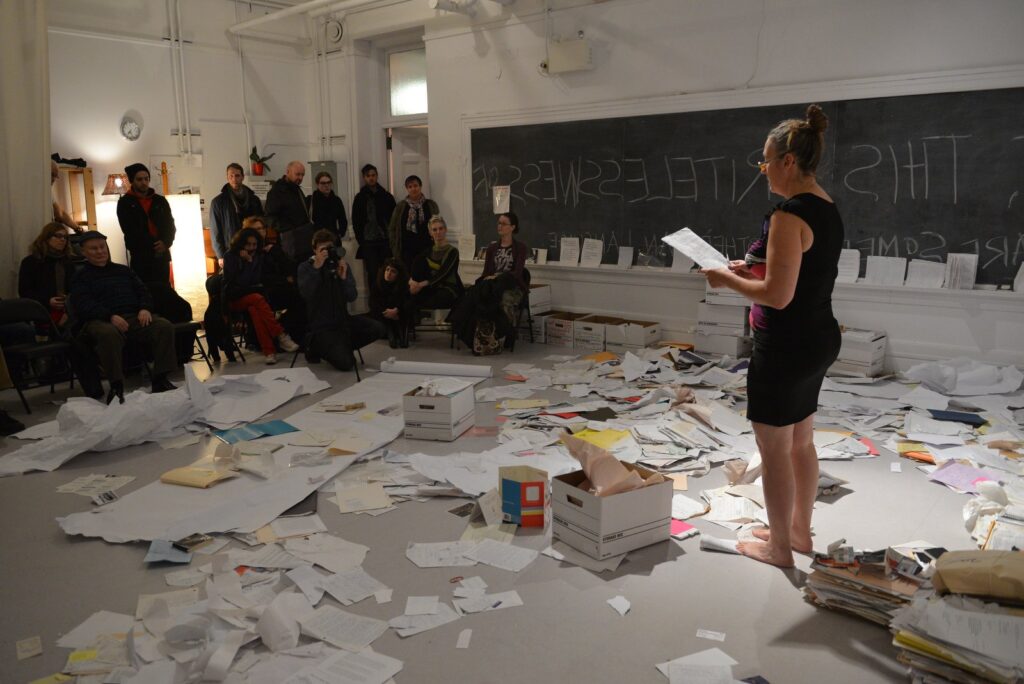

AC: I’m trying to remember what my first experience was. I don’t think I had my notebook with me, at that point, but it was similar. There’s a bit of a parallel in this interesting way, because I think lo’s performance was so much about putting herself and her physical ephemera on show, and even to the point of letting the audience walk on it or dance in it, or pick up pieces, or read through the archive and sift through to find things that resonated with them, but you’re absolutely right— on the other side, especially because it was a durational work and there were so few people there as audience members during the time that most of the action was taking place… there were probably only about 10 chairs. But when I was there, she would routinely speak to the audience. Like, at one point she found a penny in the archive, and said, “oh! Here’s a penny!” and she recognized that there was another artist in the audience that was doing a project that involved pennies and she gave it to him for his project!

JS: (laughs) So many times she would find things in the archive that were actually connected to someone who was coming, or who had just left the room: other artists or friends that had come to see her perform. I thought that was pretty striking, too. The way she responded to the material that implicated others more directly.

This process she was going through, I like what it made me think of in terms of research and art, and how research can be art: this kind of broadening out of what art practice can be. It was performance and it most definitely resided there, but it demonstrated that pragmatic and conceptual space of artist-as-researcher— the practical action of making a thing: such as in that period of time when we were actively involved in searching the archive with her to find items to make a book, and then the importance of her reflective time: the thinking about and contextualizing what she was finding. This work was completely self-reflexive, particularly because it was all happening in a public space. It was like this empirically personal meaning-making-meaning-making-meaning-making— the entire time.

AC: Yeah! There are two things about this that are really interesting to me. One is the question of labour and artistic labour, and you and I have talked about this a bit in terms of administrative labour. In the culture of artists and arts workers, there is often the need to justify your labour in terms of research. But then also, the fact that much of that labour is very invisible, and there is sort of this economy of the arts where people who are not involved in the arts have lots of assumptions about our work in terms of career fulfillment. There’s the persistent idea that if you’re an artist, you do it because you love what you do, not because it’s urgent, or because you want to make a living. Or, “you shouldn’t think about it as work because you enjoy doing it.” And what is really front-and-centre for me in lo’s piece is the time and the labour that goes into extracting the material from a research process.

JS: Absolutely. The value hierarchies of labour in the arts and within arts institutions is an issue that gets spotlit from time to time in discussions about cultural economics. On one hand, the presentation of the issues are usually rightly addressing the ongoing matter of artists not receiving equitable pay for their work (or any pay in far too many situations), and then on another hand there are hidden or what you called invisible artistic labours that really don’t get discussed much. The work done by employees, volunteers, and interns in arts institutions that are ‘behind-the-scenes’ so to speak. The pragmatic doers who work in the spaces in between art and artist and audience and institution. There are gaps in acknowledging the value of those labours and labourers. Often the value of something like arts research is reified as outcomes-based… findings-based, rather than also valued as a creative process or practice. Other forms of arts institutional labour get overlooked as well, as you mentioned. A lot of so-called non-artist labour is in fact extremely imaginative and requires creative forms of engagement, such as the ways many arts administrators need to be flexible ‘on the ground’ with their practices and methods when working with artists within the institutional structure… it really is a question of why we recognize some forms of creative agency as artistic labour and not others.

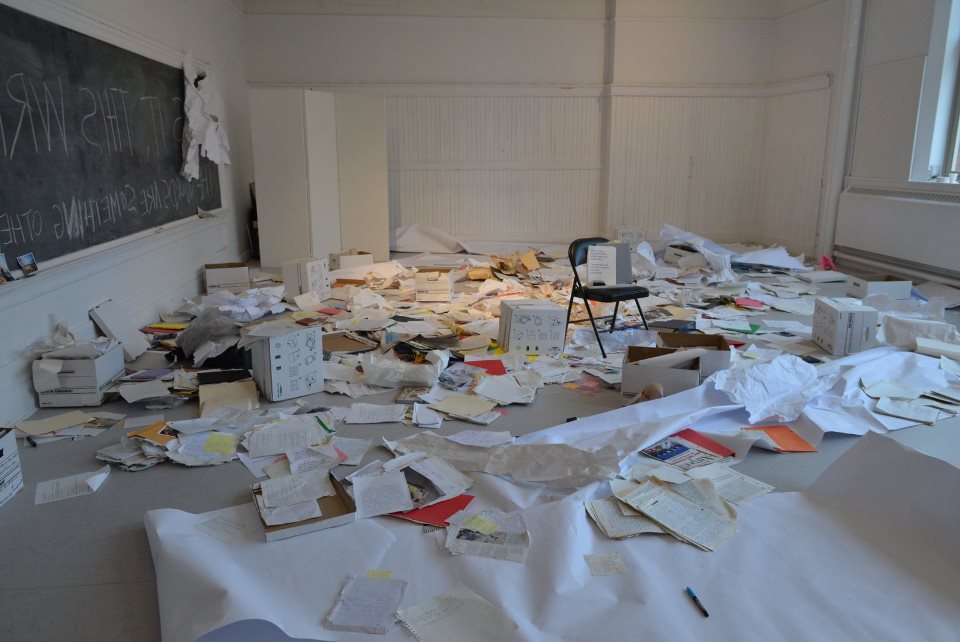

It makes me think about the constraints that every art practice has. You’re always working within or against the conventions of your own process or of your discipline… plus the restrictions of time and space or whatever. Thinking about lo’s performance, I wonder how this version was perhaps different… and I think it would be so interesting to know how she has approached this archive-intervention and self-critique in other contexts. She came with a rigid-seeming schedule, and a unified aesthetic of fragments packed in banker-boxes. When I left the room the first time it was still in a decent state of order. There was a pile of boxes, and only one box had been opened, but it was still relatively neat. But when I came back a few hours later everything was in total disarray.

AC: I don’t think I ever saw it looking orderly. I didn’t see it in the morning.

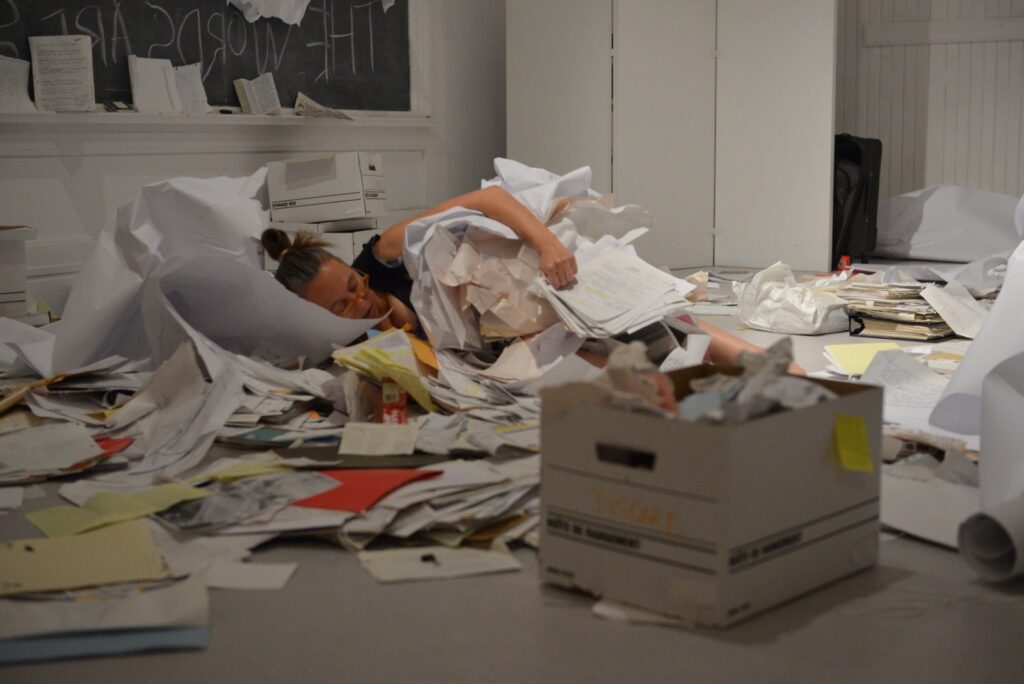

JS: It was very orderly in the morning, but when I came back around lunchtime it was just Kaboom, stuff everywhere. People were walking on it, dancing on it, and it was an overwhelming sight. Just thinking about that transition from the order to explosion… the world is kinda chaotic, so any attempt to make art, have a practice, or basically do anything is constantly going to be contending with that potential chaos in some way. This human process of meaning making and questions about how we can do that authentically… oh yeah! That’s it, I had made a note about Gestalt (laughs). I felt that in some ways lo’s process was maybe reflective of the Gestalt approach to psychology which proposes that the mind makes wholes thanks to innate self-organizing tendencies, and is interested in how people can manage to have meaningful perceptions in the face of a world that is immensely chaotic. The Clearing is maybe an interesting example of that sort of notion, especially since lo used the archive to structure her memory-chaos. This impossible archive is one that can come alive.

AC: Yeah. To make it into a coherent narrative even though the archive inherently resists that kind of narrative. I’ve been thinking about that in reference to the whole festival, because, the experience of so many of the works that we encountered, and so much of performance art in general, is that things start out very methodical and then, at a certain point, entropy just takes over, and… (laughs). Basil AlZeri’s piece was a perfect iteration of that! He started out with this clean white shirt and this clean white table and everything was so orderly and he had a very regimented idea of what he was going to do and then all hell broke loose! I think performance art in general can be a really potent manifestation of entropy in the universe and in our lives. There are lots of other things performance is really good at, too. But that sense of all-encompassing entropy is unique to performance, as a medium, for me.

JS: I like this idea of trying to sum up the festival itself and failing marvellously because it can’t be done cleanly. Your Performance Art BINGO nailed it with so many of the kinds of things that might happen, and similarly what I was expecting was that there would be threads, thematic connections, that would emerge. I figured that I would be able to weave these into some sort of synopsis of the festival as a tapestry or like an art ecosystem or something, but no! I can’t do anything like that. It would be doing a disservice to what was presented, and what we’ve seen and experienced. Other than what you’ve said about entropy, which is totally right I think. There is a lack of order, and you can’t predict. So… I guess that is the summary, and that’s so beautiful.

AC: I ran into lo the other night and she mentioned something that had not occurred to me. She said that one of the people who had seen the performance had expressed a kind of shock at how personal her performance was, and said that they didn’t understand how she could make work that was so personal. And that person compared her work to Terrance Houle’s work and Nathalie Mba Bikoro’s work, in that they were all really personal. That struck me as a really interesting comparison, and I was wondering if you felt (as you said at the beginning of this conversation that you felt vulnerable or on display sometimes in your role as blogger) that her snippets that she chose to read and the reckless abandon with which she chose to read them, did you feel like that was personal? Did you feel like you were invading?

JS: Well, I guess it was obviously personal, but what I noticed was that I didn’t feel like an audience member when I watched her work. When I got involved and was participating or even when I just sat on the side I didn’t feel like I was watching a performance that had any separateness and therefore she seemed to be very vulnerable because she was so accessible. The sense was that even though she had done it before (this sort of performance with her archive), it did seem still that there was some flustered side to her because she didn’t know what would be found.

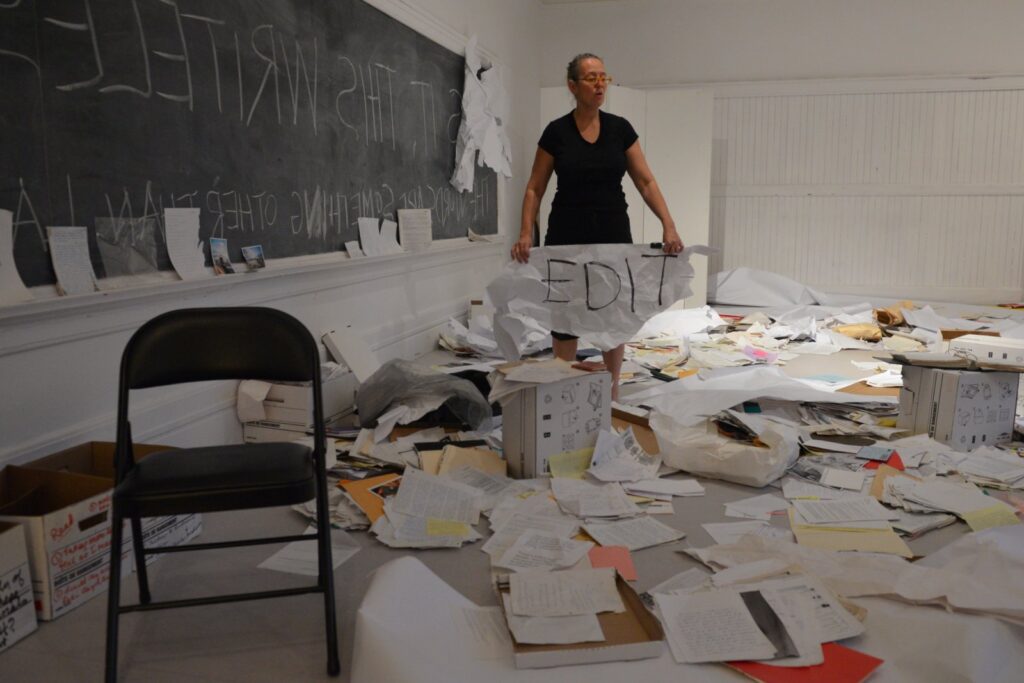

At one point she was reading something she’d picked up randomly and it was about her thoughts on pornography, and she got really embarrassed and defensive — “I don’t think about porn! I don’t write about porn! What is this? Pornography!?” She was clearly concerned about the insinuating impression this might be giving which she was obviously not comfortable with. Then she realized that the notes were probably for an essay she had been researching for a particular class, and then her body language and tone relaxed, probably because it made sense to her and the lens was one she was comfortable with…an impression she felt was appropriate, for how she felt she wanted to be perceived. So, I think she exhibited a desire to be seen but not to be judged, and to me that is very personal. It was like she needed to see and be seen in the spirit of generosity. It mattered what we thought. I didn’t feel it was self-involved, which is a critique that could be leveled at a work such as this, and that the reason it stayed clear of that was in her presentation. She made the difference because her presentation of herself was more about our engagement and presence and how we interacted. She was looking into people’s eyes and talking to them and wanting to explain and wanting to connect. That is what it felt like. So, of course it was very personal as an experience and that’s part of what it made it so good.

AC: I also didn’t get the sense that it was at all self-involved. What’s interesting is the way the work of constructing the narrative also desensitizes you. At one point when I came in she was reading about the dissolution of a few friendships and it wasn’t entirely clear what had happened but for whatever reason these people were no longer in her life. The way she read about it was very calm and collected, but it was inescapable that at the time those experiences must have been incredibly emotional. At the end, when she had done a costume change and had put on her dress and it was time for the presentation of the work, I found the fact that those personal moments of flusteredness or vulnerability or emotion or distance or confusion or realizations about not caring about something any more… the fact that those expressions kind of fractured this more official presentation was really helpful, because the piece, like you said, could have been very rote, but instead she made it feel like she was walking through it with us.

JS: She was making her archive come alive through her process for us, but it wasn’t like she was reliving it nostalgically, it was instead like she was observing, almost voyeuristically, her own life. She was playing, and playing with her own narrative. Maybe many people have had the experience where you find something you’ve written and you don’t recognize it, you can’t connect yourself to it.

AC: You’re not emotionally involved in that circumstance anymore.

JS: Yeah and that process… I don’t know. I don’t know what that is.

AC: I agree, but I want to avoid being romantic about it because she wasn’t romantic about it.

JS: You’re right, there’s no reason to make it a poetic expression. But it is somewhat of a phenomenon, isn’t it? Of memory and absence, maybe? But yeah, she wasn’t romantic. This was a process and she honoured that process, but was still a human about it. Contradictory, vulnerable, creative. There was flexibility. There were points when she would announce that she was off schedule, “we’re doing this now instead of this…” just because, and even though she didn’t need to share that explanation she did because it was part of honouring the process she had outlined. Making it known that it is important. That the process matters.

***

And, that’s a wrap for the 2014 7a*11d International Performance Art Festival Blog!

See you back here in 2016.