By Natalie Loveless

The space has chairs on two walls. In the center lies a bolt of red and yellow mottled cloth, three bottles of juice-like liquid (yellow, orange and red), three wine glasses, an orange, apple and banana stacked on three sheets of tissue paper (again, red, orange and yellow), and a long spiral of some kind of children’s candy encased in a tube of plastic. There are three books—Perform, Action, and a French edition of John L. Austin’s How To Do Things With Words—three sheets of drawing paper, and two markers. A performance art still life.

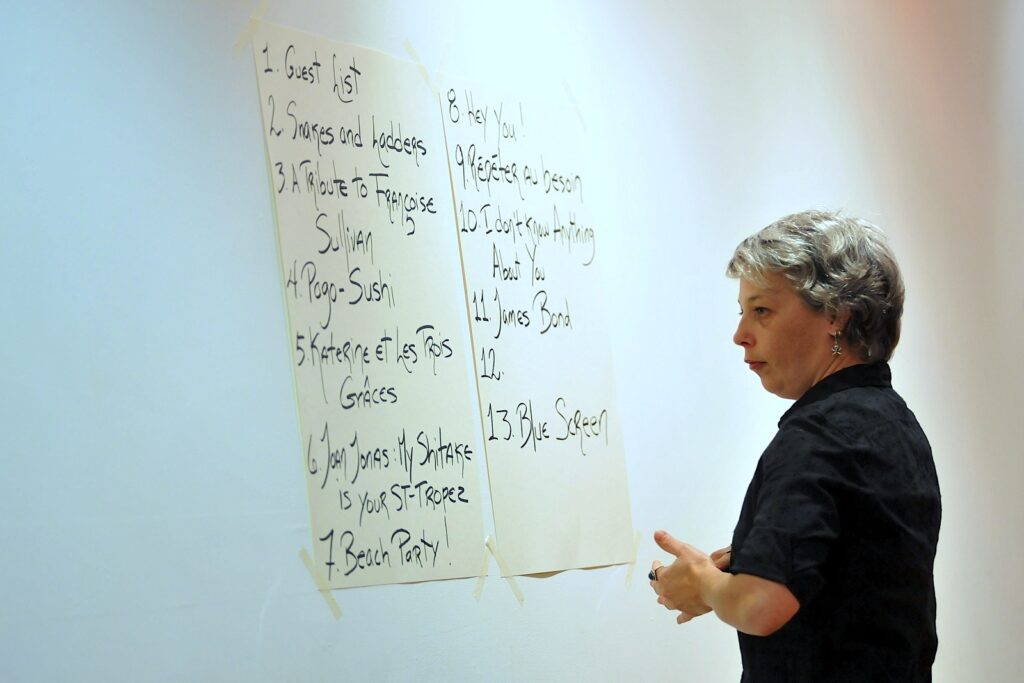

As the audience mills around, the performers begin, almost imperceptibly. I don’t even realize the performance has begun until a hush falls over the room—until enough people having stopped talking and begun paying attention to the performers (Anne Bérubé and Victoria Stanton) writing on two sheets of poster board (orange and yellow) against one of the walls where the audience is seated. Bérubé dictates the following list to Stanton:

One: Guest List, Two: Snakes and Ladders, Three: A Tribute To Françoise Sullivan, Four: Pogo-Sushi, Five: Katerine et les Trios Grâces, Six: Joan Jonas – My Shitake is your St Tropez, Seven: Beach Party!, Eight: Hey You!, Nine: Répéter au Besoin, Ten: I don’t know anything about you, Eleven: James Bond, Twelve: (number twelve is left blank), Thirteen: Blue Screen.

Bérubé and Stanton move to the opposite side of the space, the side we’re facing. By now all attention is on them. They put up two more pieces of poster board, Stanton directing Bérubé as to the straightness of the panels before dictating the list (the same list) of items. Bérubé has a thick French Canadian accent while Stanton is clearly English Canadian. The juxtaposition of accents places us immediately within a particular politics, whether willed or no—a politics of utterance. Same list, performed twice, heard differently. Meanwhile, Sylvie Tourangeau sets up the juice and glasses on a small pedestal at the opposite side of the space and and asks the audience if someone will help her carry the bolt cloth. Someone does. Tourangeau gathers the fruit and tissue paper, sets them up at this side of the space, and asks another audience member whether the banana is best perched on the apple or on the orange. The audience member indicates the orange. She asks another audience member what a pile of masking tape rolls look like. Stairs, perhaps? The audience member suggests that they look like a cake. A cake! Ah! responds Tourangeau and then, after asking how the markers should be arranged in relation to the masking tape cake, she places them inside like a vase and walks to the center of the space.

What is clear at this point is that we are witnessing actions or sequences that are loosely scripted. Attentive to the interior coherence of each action and its sequence as it unfolds, step by step, the TouVA Collective is, in some way, following the dictated list. What is unclear, and is only to become more and more unclear, is what the exact relation between the actions and the listed items is. Instead, we are brought firmly and unrepentantly into their private coded and experimental world. At one point in this world Victoria Stanton enters the space with a platter-like rectangle covered in a mix of glitter and little alphabet-shaped letters. As she slowly, ceremoniously, tilts the platter to let the alphabet glitter whoosh (quite beautifully) to the floor, the following imperative is revealed, written in glue: extract it. I don’t know exactly what I am meant to extract—perhaps meaning from among these absurdist actions and utterances?—but I will accept that order, now, as I reflect on my experience of the performance.

Extract #1: Together, Tourangeau, Stanton and Bérubé take a deep breath. They unfurl the bolt of cloth and cover the length of the space. At one end of the space, Tourangeau lies across the cloth, width-wise, while Bérubé and Stanton stare at each other through the cardboard tube the cloth was wrapped around. One is leading and the other following, but it’s unclear who is who. Like a mediated mirror game we follow their dance. The action completed, they cross to Tourangeau and roll her from one end of the space to the other. As she rolls, her hands stick out of the cloth overhead, at first limp as if dead and then gently dropping first one, then another, then another penny onto the floor at uneven intervals. With the first penny I’m unsure—maybe an audience member dropped something? By the second penny it is clearly Tourangeau. Progressively, it becomes clear that with her hands she is directing the actions of Bérubé and Stanton. They roll her this way and that and eventually unroll her completely. Bérubé and Stanton take her place and lie across the newly laid out cloth. Tourangeau brings the cloth up over them as if to tuck them in. She then places herself between them, holding a push-up position as long as she can. She pauses over the cloth as if to do something, but doesn’t and wanders offstage with a look both gleeful and naughty.

Extract #2: Bérubé, Stanton and Tourangeau enter the space, each with a marker and a piece of white poster board. In concert they tape the poster board to the floor, step to the left, and lie face down with their right hands holding marker to paper. They begin, one by one, seemingly in response to each other, to tap, squiggle, and otherwise make sounds with their (capped) markers. Somehow having signaled each other they each, then, remove the tops of their markers one handed and begin to write. The audience slowly—once the ice has been broken—stand up and crowd around to read the messages. Scrawled, drawing-like, and blind (each of their heads is turned away from the paper), the writing is mostly illegible. They finish the action by rolling back and forth until piled together.

Extract #3: Standing in the center of the space, Tourangeau, Stanton and Bérubé each hold a book. One is called Action, another Performance. These flank a French edition of John L. Austin’s How To Do Things With Words. The women begin a round-robin call and response riffing on Austin’s central example of the performative utterance: the “I do” uttered in a marriage ceremony. Do you take this commitment? I do. Do you take this seriously? I do. Do you take this lightly? I do. The women play with the I do in a context famously considered by Austin to be unfelicitous: the performance space. Bérubé and Tourangeau leave the space. Stanton, left in the space, pours herself a yellow glass, raises her glass to us and stands still. We wait. She doesn’t drink but returns the full glass to the table and leaves the space.

Extract #4: The three performers have left. There is a pause. The audience looks at each other. (What happened? Is it over?). The wait becomes uncomfortable. Just as it is about to become too too uncomfortable, Stanton comes back with some yellow folded clothes. She changes shirt. Pants. Socks. Then Tourangeau and Bérubé come back too, having changed into red and orange respectively offstage.

Extract #5: Bérubé gets into an argument with either Tourangeau or Stanton—it is unclear which. She puts on a hat and purse and leaves the space. Half of the audience can see her outside and laugh. Those of us on this side of the space have no idea what is going on. Stanton joins Bérubé outside. Tourangeau drops the banana and leaves. Bérubé and Stanton re-enter, Bérubé hands an audience member a cigarette that she lit while outside, and they both follow Tourangeau out of the space. We wait, trained to expect long pauses, for them to return, but they don’t. An audience member tells us that it’s over. We pause, unbelieving.

No, really: it’s over.

The performance ends as it began, with uncertainty. The 7th Sense operates much like life—it begins before you really know it is happening, is heavily structured for much of the middle, and the end takes us by surprise.