By Andrew James Paterson

Late in the afternoon, I found myself with idle time so I decided to check in on the Creative Residents working out of Toronto Free Gallery. Chaw Ei Thein’s mural—Quiet River—had been extended much further than what I had briefly glimpsed late last week. A row of Burmese monks at the top of the mural gave way to monks with the same faces and tops of bodies, but without legs. Chaw informed me that quite a few Burmese people living in Toronto and also many citizens of the Bloor-Lansdowne neighbourhood had entered the gallery space and conversed with her as she worked on her mural. Most of the Burmese visitors had responded to an advertised notice, and Chaw was pleased by the range of respondents. Chaw Ei Thein will be making a presentation next Saturday afternoon.

Meanwhile, Glenn Lewis was choosing appropriate music for his upcoming presentation next Saturday afternoon. He had assembled four bags of litter or trash or whatever that he had collected during his two walking excursions previously this week. Lewis had thoughtfully left a note indicating that his garbage was not garbage.

After a goat roti in the nearby Vena Restaurant, I headed down to XPACE. The first performer of the evening was Quebecois artist Francis Arguin, whose presentation was titled Introduction to the body-orchestra. And it was an orchestral performance, although alternatively offhanded and then intense in its tone. His set was simple—a chair, a bottle containing water, a Styrofoam cup, and a nondescript bag containing probably something(s) mysterious. He sipped water from the cup, and then began slowly moving sideways on stage rather stiffly, not like a fluid dancer. He also began making motorific noises, like a car idling or waiting to make a move. He pointed a lot and used the pointing and the growling to create broken rhythms.

Then he reached into the bag, produced clear plastic tape (a commonplace in many performances) and some bug-eyed blue cardboard-like sunglasses (no glass). He sat down and began tapping his feet very speedily—creating express train rhythms. He toyed with his shirt, while I noticed that he was wearing yellow socks. He announced that his name was Francis, and that he might try to kill his name. Francis, not Francois or Frank. He announced that his name is Le Petit Shirt That He Wears. He took his shirt off revealing a red T-shirt was the letters spelling FRANCIS. Another identical shirt underneath also spelled his first name. Another not quite identical shirt said his name was FRINCAS. Not a clever anagram, but a reject typo. He picked up a can of something that he shook. It was paint.

Arguin held up cardboard sheets in which he had made holes resembling shapes. He held the first one against his white T-shirt and voila, a table. Then he shook a can of paint which was revealed as being red. He’d pile incongruous objects on top of each other on top of the table (electric guitar, milk bottle, a river, an umbrella, and many more). He made a non pop-art T-shirt, which was a singular original. It could become a multiple if screened, but it could never be painted exactly the same way twice.

Another colour was necessary, so he produced a yellow object that may have been a fan or a hanger or a series of pyramids. He dropped little flying objects from this hanger, labeling them as things that fly from the sky. “Snow, bomb, rain, birdshit.” He produced a clear plastic top and matches, lighting the match, securing it with his left baby fingernail, and then drawing an arc. He dropped the match onto the floor (oh dear, more fire), rolled up his trouser legs, sat with his back to the audience with his feet on red cushions, and began slowly moving the contraption backwards. As he cleared a path through the centre of the audience, it became clear that this was a durational act that would not be followed or succeeded. And it was. Arguin had linked four of five or six movements into some sort of site, if not a symphony. The performance was not bombastic; it was on the verge of being precarious.

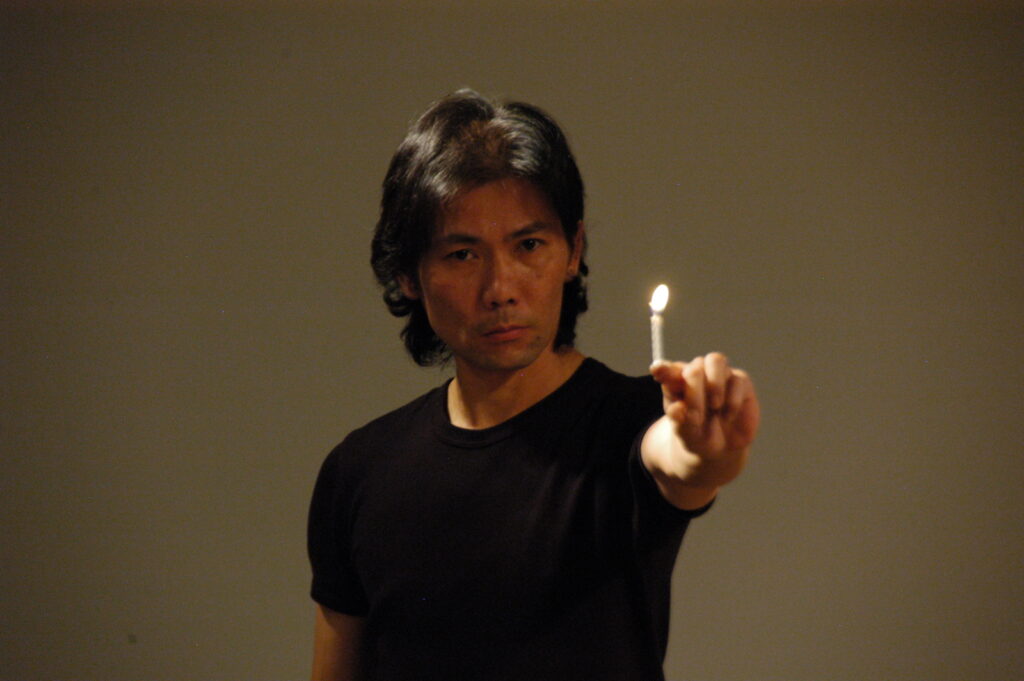

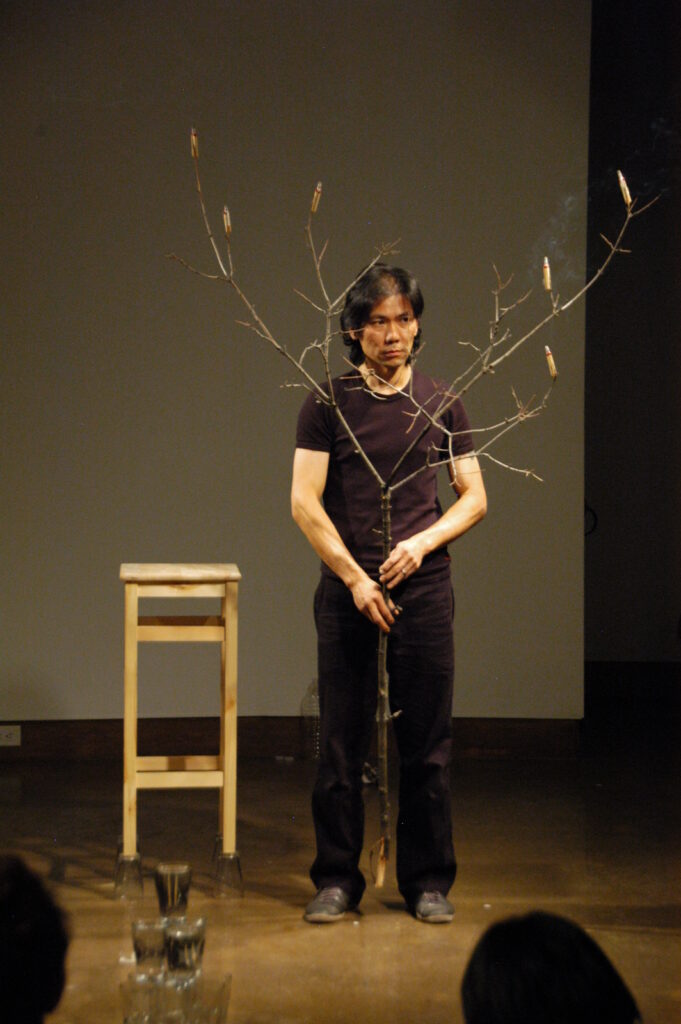

The second performer of the evening (main floor, no basement-dwellers tonight) was Singapore-based Jason Lim’s Last Drop. Sure enough, he had a series of clear glasses carefully laid sideways on the floor, with two bottles of clear water. He also had a pile of dessert-sized plates, and a leafless small tree. He selected four glasses, and placed them under the legs of the table. Lim stood several of the other glasses vertically, and began mounting the glasses into a quasi-pyramid. Two layers of glass on glass, and then one on the top. He poured water into the top glass and into those below it—without spillage. Almost magical.

He moved the tree over beside the chair area, and lit a match. He produced small stick-ish objects that he lit and set burning. They were odourless—they weren’t cigarettes or candles and, if they were incense, then they sure didn’t smell like any variety on the market. The stick-like objects were spread around the tree—smoking and occasionally flaring. He grabbed the clear tape and wrapped it around the tree and the chair, making almost an anti-Christmas sculpture for the almost deserted living room.

Now he picked up the plates that had been waiting for him. He began stacking plate on top of glass on top of plate, while using full glasses of water. He built an eight glass-high tower and it was perfectly balanced and secure.Then he played magician again with a full glass of water. He’d hold the glass until it seemed to slip out of his hand from pressure of duration, but then catch it safely. He repeated this gesture sixteen times. Eight glass tower plus sixteen safe catches makes twenty-four. Then he played close-up basketball with the remaining glasses, dropping them into each other with only minimal chipping. There was a lot of water to mop up on the floor, but negligible broken glass. Very impressive. Lin stated in the festival catalogue that Last Drop was intended to invoke sound and silence, fullness, and emptiness. The performance did indeed involve refurbishing and draining, and sound always threatened to break into the silence. But this performer retained control—accidents were never part of the equation.

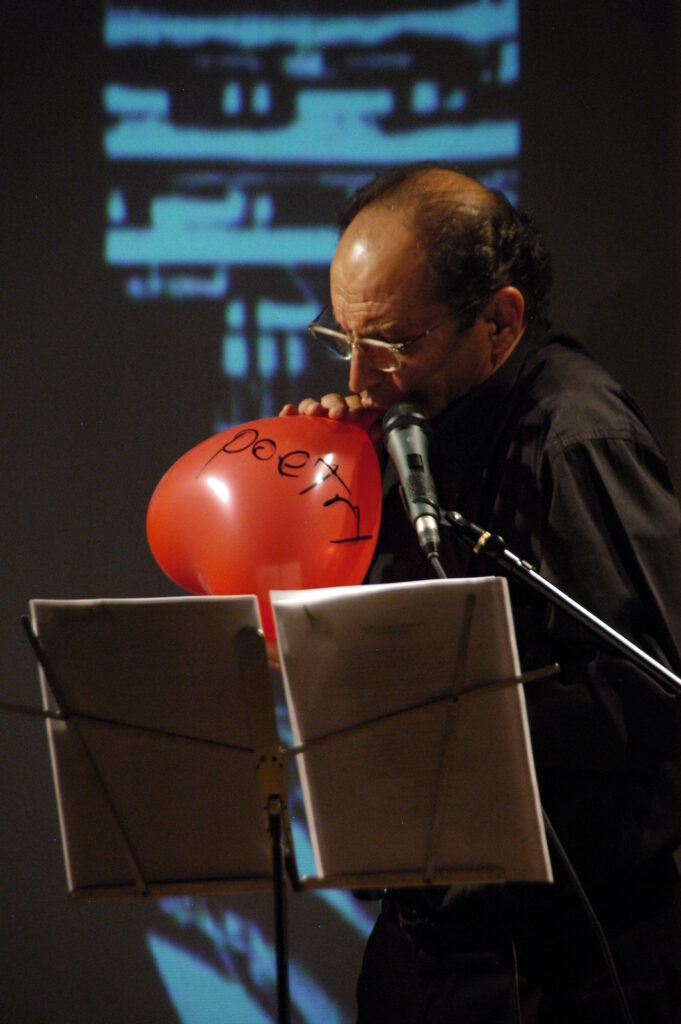

The final performer of the evening was Nicola Frangione from Monza, Italy. Frangione performs Voice in Movement—performance poetry or what some artists describe as “art dramaturgy.” He did not simply stand and read, he used his entire body. His words and his body were in beautiful synchronization—it was not as if one needed to cue the other. And he used prerecorded music to set rhythms for his movements, his vocalizations, and the striking black and white images projected to his left. Roll text of translated excerpts segued into complex visuals. These images were of musical stanzas, of scientific images, and of words themselves as pictures, but they would become deliriously abstract in tandem with his hands and hips and feet. Nicola Frangione is a man with an idiosyncratic sense of rhythm and thus he understands the beauty of both screen-saving and auto-oscillation. Make a sound, make a picture, let it generate and regenerate and chase its own tail many times over. The fourth composition was almost eponymous with the poetic presentation: “vocecevovodce.” Voice this voice this voice et cetera—it consisted of sound alliterations of the word “voce” (voice!); “while poetry is bouncing, the poet is jumping.” And the projected images were mantric, and all in black and white. Colour was unnecessary.

In the reference sheet that the artist thoughtfully had distributed to the audience, Frangione’s second composition “Ittoosang” is posited as a rather Cageian exercise. It is described as a piece for the listener, who is given a series of instructions to follow for a specific duration. Except…the sixth command states that “for pleasure’s sake you can avoid following these instructions.” Frangione concludes his paragraph on this second piece of the evening with the following zinger:

“Instructions are always useful for those who write them while they are hardly useful for those who follow them.” Zen, or anti-Zen?

Nicola Frangione’s set was brief and fulfilling—he could have continued for a good deal longer and maintained both surprise and beauty. Voice in Movement was a multimedia performance, in the best senses of that overburdened and frequently reductive description.