By Elaine Wong

The third day of the festival was characterized by performances that transformed a range of spaces.

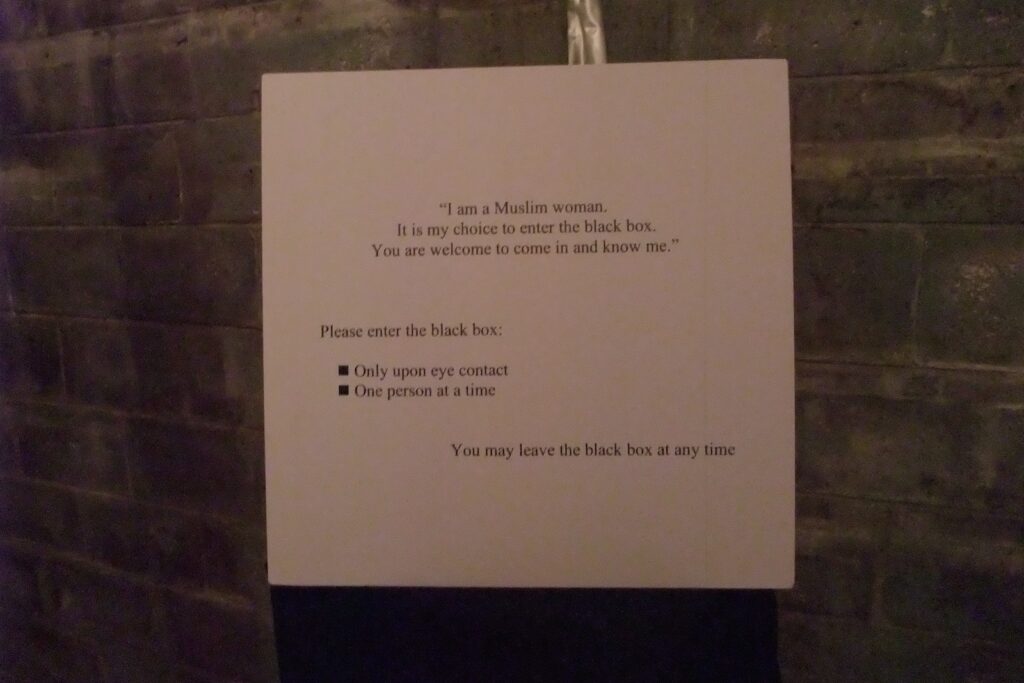

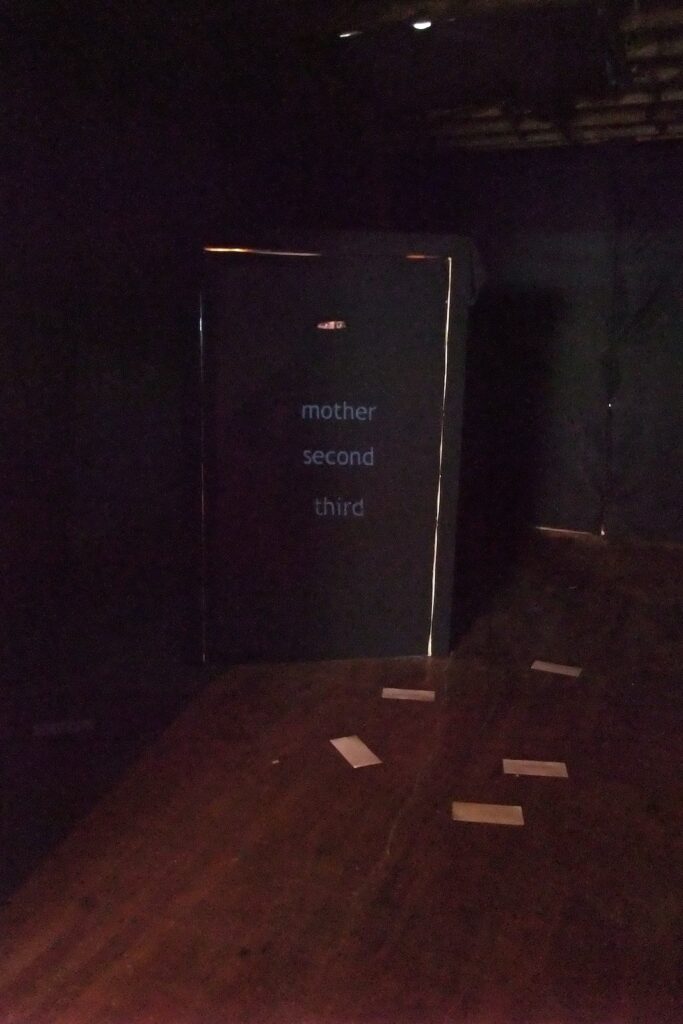

Simlâ Civelek created within the back space of the Toronto Free Gallery a tiny world unto herself—a small wooden box draped in black cloth. Civelek prefaced her performance with a placard stating “I am a Muslim woman. It is my choice to enter the black box. You are welcome to come in and know me.”

One of the box’s walls bears a small slit at eye-level, an image that immediately conjures up the metaphor of a burqa, but also reminds me of the mail slot on a door, an observation made more potent as pieces of paper are slipped through the slot and flutter to the floor in small, persistent attempts to communicate to the outside world.

Issues (and perhaps the fallacy) of choice are highlighted. Onto the walls of the box are projected a poem that highlights Civelek’s lack of choice: “language has left me” and “long gone are the days i picked every sound word voice.” Yet those who enter the box are given a test, asked to choose from multiple interactions in different languages that will structure the action to happen. Who then is in control?

A little bit of guilt filled me as I circled my choice—I am one of the people who are limiting her, choosing for her “what emotion, what idea, what address” she should use. She recited for me her poem in Turkish, eyes closed, mouth shaping the words, but clearly uneasy.

Civelek shared with me an interesting piece of information: at first the box was a familiar thing to her. It was her box, her life. But after the six hours spent inside its warm confines, it became somewhat alien, oppressive—she could not think, she could not react. By the time I had entered her box, she was no longer in control. She told me that entering the box was her choice, but what happens afterwards, once she lets people in, is a third entity that exists outside both the bodies within the box. That which she controlled in turn begins to controls her.

And yet, in contrast all this, was the interaction of a small child who knew Civelek (her Auntie) was in the box. The box was irrelevant, the concealing cloth was a simple barrier, the social and cultural implications were meaningless; the identity of the woman inside the box was immutable to the child. Upon waving goodbye, the child’s mother murmured “look, Auntie is smiling with her eyes”—the only parts of Civelek that could be seen from outside the box. That statement alone is more poignant that anything I could write.

In the parking lot behind Queen Self-Storage, Mahan Javadi had assembled a large portion of his worldly possessions with the intent to destroy. Part of the series Project Zero, ‘Space‘ is the culmination of a three-month process to reduce and streamline Javadi’s life.

In the dark and dirt, lit by floodlamps, he took to destruction calmly, contemplatively, achieving an almost zen-like peace as he ripped the pages from books and smashed miscellania to pieces with a sledgehammer. But what took the most amount of time in the performance was the sorting process, going through each item individually and deciding what to do with it. As he went through, there was an inescapable feeling of something akin to mourning—it was clear that as he went through his physical possessions, he was also going through his memories as well. The act of destroying textbooks and artwork from his college years read as a filtering of the past, a destruction of the baggage of previous selves in order to be free to move on into future identities. Unironically, he unearthed a magic 8 ball and asked it a question, musingly, before putting it too to the sledgehammer. I guess you can’t predict the future, just prepare for it.

Although his original intention had been to destroy it all, Javadi admits that as he was going through and sorting the objects, there were some things he just couldn’t destroy—his childhood teddy bear, for one. He was hesitant at first about the authenticity of donating, unsure of whether it was an idea stemming from societal compulsion rather than a real decision coming from within him, but in the end it did become a genuine option for him. He hopes that the emotions of this performance will stand as encouragement to collect less content and simplify his life.

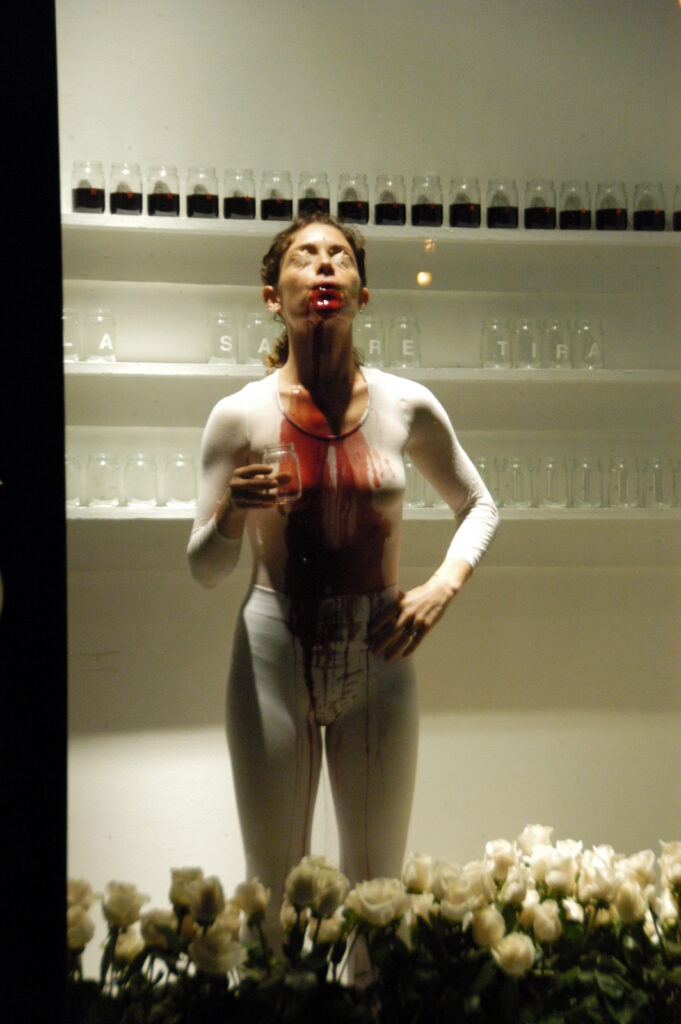

Even XPACE was given a change of pace as Alejandra Herrera performed 51 Starts in Reinohelen in the gallery window, making herself into an image to be watched either from the other side of the glass, or obliquely from the inside.

On a series of shelves set up behind her were numerous glass jars, filled with red wine and adorned with a single red star apiece. On the middle shelf, the jars spelled out the phrase ‘La Sangre Tira,’ which she later translated as ‘Blood is thicker than water’ in lipstick on the glass. On the floor of the tiny cubby were vases of white roses and Herrera, clad in a sheer white bodysuit with tape over her eyes, was forced to negotiate the physical confinements of the space blindly. Throughout the night, she carefully fumbled for each jar, pouring the contents into her mouth and letting it overflow and spill down her body. By the end of the night she was soaked and kneeling in a pool of blood-wine amongst the flowers, before finally chewing the petals off a rose and placing the crushed petals into a jar.

…Forgive me if I hesitate to post my understanding of this piece.

The idea of ‘Blood is thicker than water’—that bonds of family are stronger than bonds with others—is a positive one, but to me Herrera presented herself as a sacrifice to this idea, drowning in blood. The roses were a funerary white that became speckled with wine, like spray from a wound. Trapped and blinded, asked to endure for the sake of an ideal, Herrera embodied the irony of faltering with confidence, slowly bringing herself to the end.