By Geneviève Wallen

As a writer commissioned to report on this year’s 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art, this was the first time I had attended the entire festival. My focus as a curator and the circles that I navigate are mainly rooted in the visual arts, and my experience of the works is informed by my education and positionality as a cis straight Black woman, able bodied, Francophone, and a settler on this land. My curatorial practice focuses on the manifestation of healing spaces in the arts, as well as the ways in which art can galvanize communities to co-create pockets of collective care. Thus, my observations for this 12th edition of 7a *11d are deeply influenced by these framings/positionings. The word tender becomes the primary lens through which I deconstruct each performance—tender as a vessel for self-love and communal care, as a soft wound, as an offer. I consider this word as a grounding element to decipher the curated series of movements and stories.

This text is structured as a progression from narratives depicting various forms of intimate interventions to broader collective experiences. Over the writing process, this essay has taken the form of a compilation of short performance reviews, allowing space for each work to be remembered or re-acquainted with—ephemeral, a performance lives through the stories we share. Therefore, tender as a connector is a loose vessel for this observational account. The nuances of the word can be found in the ways in which I highlight certain gestures or details in the artist’s process. Artistic choices that connected the pieces together, such as the inclusion of rituals or ritualistic behaviour, were very present throughout the festival. Energy cleansing, religious or cultural re-enactments, repetition of movements, and the making of symbolic shrines developed into interpersonal and social transformative platforms. In addition, there was a palpable urgency to address the intrinsic failures of current dominant socio-political structures as well as to challenge naturalized belief systems. Lastly, I noticed a common desire from the presenting artists to design performances that are immersive via the use of space and emotional responsiveness. Actions such as tending, gifting, attending, caring, acknowledging, healing, mending, manifesting, labouring, and exchanging were often inherent to the narratives that were presented. These gestures give meaning to the various uses of the term tender, supporting it linguistically and visually. They also represent embodied spatial encounters and negotiations, in both the private and public spheres.

I want to warmly thank the artists for their generosity, for their time and for sharing their process and thoughts.

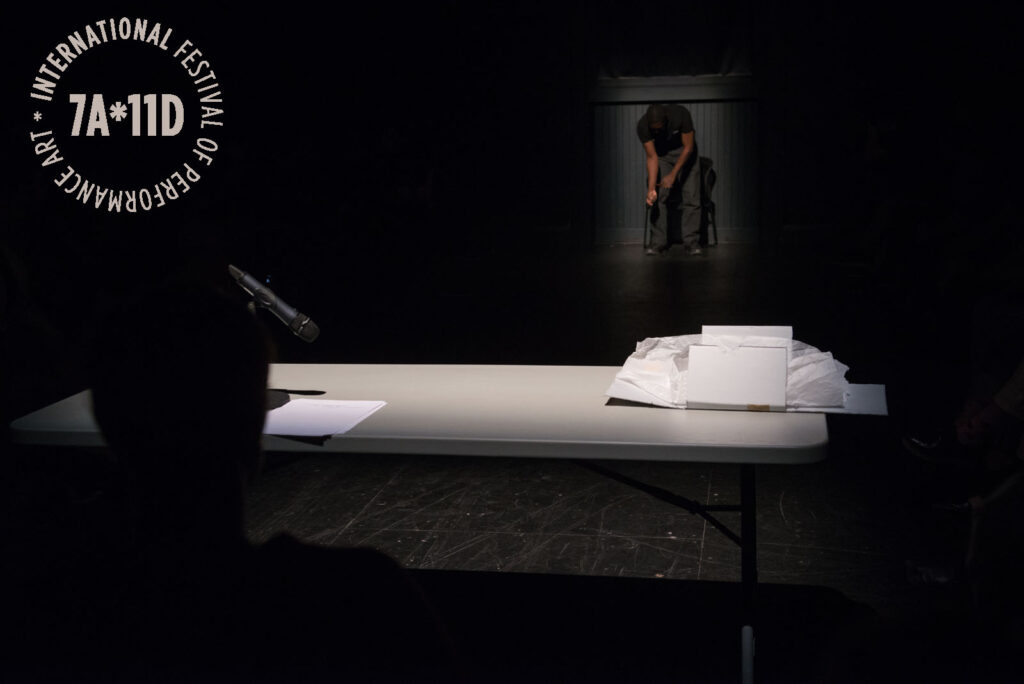

Mathieu Lacroix : Ci-après appelé « l’artiste »:

Ci-après appelé “l’artiste”: investigates the modality and the language intrinsic to the artist contract. Understood and normalized as an insurance of a fair exchange between the artist and an institution, this document weighs on one’s understanding of labour. Seated at a wooden table, Mathieu Lacroix opens a courier box in which a small stack of paper is concealed. He then proceeds to sign each sheet at the formal line: Ci-après appelé “l’artiste”:, standing as a symbolic stamp of professional status. Lacroix signs fifteen stand-in contracts, equaling the number of years practicing as a professional artist. But what makes an artist “professional”? How is one’s physical labour, discipline, creativity, and endurance legitimized and quantified in the art world context? How is one’s effort and the sacrifice highlighted, appreciated? This performance offers a platform to meditate on performance as medium and its transactional point of convergence. The work also demonstrates a desire to express the multidisciplinarity that is fundamental in conceptualizing a series of movements; in this case the artist is interested in drawing as a performative act (in a similar fashion to François Morelli, another of the festival artists) and the notion of limits in body art. After signing the contracts and placing them in a neat stack, Lacroix scrawls on a blank piece of paper, shifting the pace and rhythm of the piece with small, agitated gestures. The artist pauses to examine the newly produced artwork, seemingly dwelling on its properties. A second shift in intensity arises when the artist starts to crumple the last drawing into a ball of paper. With a crisply closed fist, he goes on to drag it on the ground while pushing his body, still seated, away from the table. With a progressively built tension and suspense, Lacroix moves across the room, between two rows of attentive observers. The narrowly focused lights highlight his tense body language. Arriving at the edge of a wall, he stands up, looking straight ahead, and takes a sharp pencil out of his pocket. He begins to softly poke the veins of his left forearm. The veins are contracted, and I am worried about what is to come. The artist is consciously toying with the public’s expectations and the idea of body art and the use of controlled self-inflicted injuries common to the genre. Most of the time, the injuries are employed as an effective and affective strategy to bring attention to specific issues. In this context, it is to bring the gesture to attention, and to question what are his limits as an artist. How far one should go to instill a long lasting impression, to offer a memorable performance?[1] Lacroix doesn’t puncture his forearm, but instead pencils down his vein lines, taking the action of drawing to a visceral plane. After the performance, still stunned by the emotional build-up created by Lacroix, I introduce myself, look at his scratched knuckles and ask: how is your hand?

Erika DeFreitas: nothing ever so straight

nothing ever so straight is an object-based exploration by performance artist Erika DeFreitas that questions what possibilities lie in one’s relationship to writing as a rhythm, as a space, as the materialization and manifestation of things. What does it mean to name things? How is one relating to objects, and what are the dimensions that they take once valued, named, owned, or on a table in plain sight? Where does one situate themselves between the lines, in the silence between a period and the beginning of the next sentence? Seated in the middle of a dimmed room, surrounded by personal objects, on the floor, on stools, in a vitrine, and on the wooden table where she sits, DeFreitas delivers an adaptation of Gertrude Stein’s play, Objects Lie on a Table. Each featured object is in resonance with the play and the artist’s everyday life. Feeling a strong creative acuteness since her first reading of the text in 2015, she has been in communication with and channeling Stein’s energy. According to the artist, a past psychic séance with the modernist author enabled her to tap into a very peculiar creative flow.[2] The artist’s revisions and performance could be interpreted as a footnote to the original text, expanding on what was overlooked by the author. For example the reference to the nuns, “Nuns ask for them for recreation. First a nun. Have you meant to have fun and funny things. Do you like to see funny things for fun.”[3] The nuns, the characters opening the play, are mentioned once and then discarded. Therefore to foreground their presence, DeFreitas revisits the aforementioned citation and punctuates her reading with the rhetorical question: isn’t funny? Her creative undertaking reveals a deep understanding and a dedicated study of the work, a special care to Stein’s creation. In her labour of noting the gaps and omissions, DeFreitas allows for characters and objects that were overlooked to re-emerge. Attending to them linguistically and materially automatically reframes Stein’s established relationships and order of things, giving life to more than “what is there to see”.[4] She invites the audience to carefully listen to the commas, the periods, the repetitions, to consider when capitalizing matters. “Let us capitalize black. black capitalized becomes Black becoming Black. Let us revisit.

Black Black

Black Black

Remember me. negro becomes Negro. Objects become when becoming subjects. Let us capitalize.”[5]

Reading through her footnotes, at a rhythm that follows the pace of her heartbeat, DeFreitas proceeds to an exercise of naming and highlighting the oddity in the familiar and the familiar in the strange, confusing all sorts of ingrained knowledge or categorizations that are taken for granted. Each page she reads has only one sentence inscribed. Speaking softly, caressing the paper slowly, the artist weighs the meaning and the emotions that one sentence carries, versus one paragraph.

Thirza Jean Cuthand: Love Is the Only Socially Acceptable Psychosis

I read Thirza Cuthand’s work Love Is the Only Socially Acceptable Psychosis as an embodiment of the vulnerable process of tending, mending and holding one’s self. The piece starts with Cuthand sitting and undressing herself as an audio recording plays. The artist’s voice fills the room as memories flow, revealing deep-seated relational anxieties as well as moments of joy and release. The artist’s story begins in the late 1990s and runs to the present, in 2018. While sitting nude on a chair, facing the audience, she drips hot red candle wax on her breast and upper thighs. The melted wax sets, and is then gently scraped off with a hunting knife. These gestures are ambiguous, but give a sense of a controlled ritual that grants emotional exploration, of meditation. The ambiguity also resides in the association of pain and pleasure, which according to the artist was a nod to past investigation of sensuality and pain as a youth.[6] After a few times of dripping and scraping off wax, the artist tends to the superficial burns with an ointment of oil and turmeric. These movements are repeated in a cyclical manner, echoing the various emotional states recounted in the anecdotes, ranging across ache, excitement, depression, passion, longing, and acceptance. Cuthand explained that a long time ago, when going through manic psychosis episodes, rituals such as the one presented on stage were very helpful in deciphering what was going on. In this performance, she recreates one of those rituals to link the experience of love with the actions of madness.[7] The video projections showcased behind her also play an important role in communicating the described sentiments. The flat landscape of the Canadian prairies speaks to her first love in Saskatoon and this turning point in self-discovery when she connected with the queer community of the region. The rural scenery is followed by images of fireworks, which could be interpreted as the signifiers of sexual/romantic passions and relational entanglements during early adulthood. And finally the last image is a view of the earth from outer space, mediated by space station cameras, representing the possibility of multiple beings simultaneously experiencing similar emotions. This last image invites self-reflection, and its timing coincides with the artist getting dressed again. It is a very honest performance that highlights themes linked to queer love, desires and fantasies, and how they co-exist with mood disorders. The interlacing of a recorded journal and live performance complemented with projections provides a multidimensional viewing experience. While the progression of the audio component is linear, I would argue that the performative elements and the projected images ask the audience to re-evaluate the concept of time and space. In Cuthand’s meditation on love, moments overlap; they gravitate around each other.

James Knott presents… “The Apocalypse in Your Bedroom” Tour

Similarly to Thirza Cuthand, the artist James Knott puts on view their inner dialogues, carrying the audience through a series of emotional states, offering a multidimensional reading of time, with every component inhabiting its own spatial frame. Both performers leave their performance open-ended on a hopeful note, at a crossroad. James Knott presents… “The Apocalypse in Your Bedroom” Tour is an immersive performance that recalls in its aesthetic the 1970s pastiche and the flamboyance of glam rock. Its narrative structure emulates the pace of a musical or a video album. Recounting a tale of self-acceptance and resilience, Knott suggests that each song encapsulates a moment, stringing the whole piece together.[8] Combining video projections, live singing, choreography, popular culture references, animation, and props, the artist produces a moving theatrical assemblage. The idea of the performance stems from the circumstances under which Knott was creating: “The Apocalypse in Your Bedroom” was conceptualized for their thesis exhibition when graduating from OCAD University in 2017. The anxiety to perform in an exclusionary system supporting exceptionalism through “artistic excellence” or “artistic genius” became the basis upon which the artist carefully built around the idea of failure, more specifically, the “queer art of failure”.[9] What if there is a way of reassessing success? This inspirational proposition by Jack Halberstam centres failure as an act of refusal against current hegemonies and inequitable socio-economic systems. Halberstam suggests that success is a heteronormative capitalist venture qualified by social norms, standards of productivity, reproduction, and material wealth, in which one’s gain depends on the failure of another individual.[10] His theory focuses then on the idea of failing often, and failing better as a counter-hegemonic option offering insights on navigating the world laterally, rather than striving for bottom-up pedagogy. Knott, who identifies as queer, uses performance as a platform to formulate alternative ways of being, moving laterally to exorcise binary formulations and social entrapments that do not cater to them. The psychological evolution put forward in Knott’s writing also discloses the trappings of cultural disarticulation in queer identities, shedding light on the emotional labour that comes with ever-translating one’s reality. This state of uneasiness is further noticeable in the laborious use of the props: the white wooden boxes that need to be rearranged every few minutes in order to fit the projections, and compose the right atmosphere. Presenting themselves as going against the grain, they find hope in patiently practicing self-love, even if it means to fail and start again. Furthermore, they suggest that the “re-stitching” of the self does not have to be an isolating exercise, as it can be accomplished with a loving support network.[11]

Cindy Mochizuki: Tenohira

Tenohira is an intimate 8-minute performance in which a very special bond between the performer and the participant is cultivated. The performer’s practice is anchored in facilitating community building through storytelling. In many of her past multimedia works and performances, she has featured folkloric stories that were passed down from her ancestors. Her aesthetic choices are self aware of the ethical responsibility around how material and stories are shared.[12] In this particular instance, the experience facilitated by Cindy Mochizuki and her stage assistants—whose responsibility is based on the role of kuroko (stagehands) in Kabuki, Noh, and Bunraku puppetry performances—feels like an altruistic act of care. Tenohira means palm in Japanese, and the first gesture of this performance is a palm reading. Sitting across Mochizuki, the participant gives their left hand for a reading; and from there as a receiver of fortune, you are invited to welcome the spirits who work with Mochizuki to guide you. Invisible forces such as a symbolic incarnation of her grandmother, a water spirit based on Sujin, the god of water and the moon goddess (who is partially Yuki Onna and Tsukiyomi), support participants through their inner journey. From one ritual to another, I have the chance to think through my emotional needs, wishes and desires. The artist’s offerings are not only material, but also spiritual. It is an opportunity for intentional mindfulness, letting go of certain energies, and being fully present. Mochizuki extends her gift of prophecy as a conduit for communal care; she has confided that she wants this performance to be about gifting, as well as exploring the potentiality of the performative space as a platform for care. Her intentions are to take each person into her care, aiming to co-create a space of reciprocity and meaning-making via storytelling.[13] Furthermore in the spirit of gift giving, Japanese sweets are offered, such as Wagashi (a type of confectionery made from lima beans and sugar) and tsukimi dangos, which are little rice flour balls served during the celebration of the Harvest Moon.[14] I remember leaving the room alleviated, in that I had been tended to spiritually, emotionally, and physically. Moreover, I had the urge to return kind gestures, to fill the rest of my day with kindness. I believe that this is what communal care does, setting a motion that drives any recipients of care to give back.

Ayumi Goto and Peter Morin: Roaming

Facing each other, Ayumi Goto and Peter Morin were carefully fixing the gold leaves patched onto their arms.[15] Though it wasn’t part of the performance, to me, witnessing this short moment of gentle thoughtfulness between close friends and collaborators set the tone for the rest of the piece. The performer’s engagement with the room and the audience was very spiritual and ritualistic in nature; it opened with an energy clearing of the space, a welcoming of new frequencies, an acknowledgment of the First Peoples of Turtle Island, and making space for ancestral presences. The premise of the work was a reflection on the spaces that our bodies occupy and what it means to intentionally situate one’s self, especially when travelling or moving elsewhere. Since both artists have recently relocated to T’karonto, there was an urgency to address those themes. T’karonto is a transient place for so many individuals, myself included. One of the questions that stayed with me from their conversation was formulated by Morin, and it goes along these lines: Ayumi, what is the best land acknowledgement that you have heard? While reading the Treaty No.13, the purchase of T’karonto between the Crown and the Mississaugas, and exchanging thoughts about their personal relationships to this land and the ones on which they first set roots (respectively Treaty 7 land and Tahltan Territory), the performers were preparing an offering. Seated across from each other, separated by a symbolic river (a plexiglass tank filled with water and positioned in the middle of the room), the artists underlined the central part of water in understanding and navigating one’s environment, and “the power of the water from the lake and the rivers in mapping the land, to create paths that transgress and live beyond human border-making”. Water embodies an important relational vessel that can’t be dissociated from land-based relations, and a receptacle for Indigenous knowledge. According to Morin “the container also speaks to how water remembers”.[16] The viscerality of the performance was beyond the words exchanged by the artists, as each of the audience members was called to action through an embodied contract made out of some sort of artificial marzipan sheet. When asked about the idea of a bodily, ingested accord between the audience and the performers, Goto commented: “we wanted people to think about the insistence on a particular legal understanding of the treaty making process and to admit where it was wrong or failed Indigenous folks in the process of initial and subsequent signings. (…) otherwise, there is the more esoteric and visceral reading of swallowing the words and actions of others (Peter and my dialogue about land acknowledgments)”. [17] As words are dubious in written history of this land, the marzipan stamped with either a red salmon or a black crow presented an alternative—within their physicality these objects provided an alternative pledge, one that refuses the treaty languages. The crow and the salmon standing as symbols of engagement, both hold a myriad of references that speak to Goto and Morin; the salmon as a gifting entity, one that gives without asking anything in return, the crow as Morin’s clan crest as a member of the Tahltan nation, offering this crest to the audience, eating crow as a first step to humility.[18] By eating crow and eating salmon the audience was gifted with new bases to start their building of territorial acknowledgement, and to be aware of the work needed to progress towards a decolonial future.

We all ate together because we are all in it together.[19]

Barak Adé Soleil: a series of movements [Toronto]

Barak adé Soleil’s a series of movements [Toronto] is a work deeply rooted in love, one that attends, protects, acknowledges and most importantly amplifies more than one voice. The acknowledgement introducing the performance highlighted the urgency in recognizing the multiple ways in which bodies are connected to one another, and the importance of carving space for plural ways of being. To further emphasize his plea, adé Soleil requested that the members of the audience enter the theater in an order and pathway that was predicated on social access and mobility—pressing on socially constructed hierarchies and one’s attentiveness to able-bodied privileges. Adé Soleil’s movements examined various forms of actions from crawling, rolling, leaning, to using mobility devices, and ultimately standing. The artist’s connection with the public was meant to be multilayered; at times it was gentle and other times more confrontational, all while investigating the weight of different stages of verticality. Even while underscoring his bodily rapport with architecture and the public space, he also highlighted how one’s humanity and desirability can be easily dismissed through numerous societal intersections, one being disability. Adé Soleil also intentionally brought to the surface the violence of ongoing archival and cultural erasure. a series of movements [Toronto] is based on the seminal work of well-known Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker: Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich (1982). The footage in Reich’s notorious piece Come Out (1966), featured in De Keersmaeker’s choreography, originates from a too familiar story of extreme physical abuse and systematic anti-Blackness. Indeed the words “come out” were decontextualized from the infamous sentence by Daniel Hamm from the Harlem Six: “I had to, like, open up the bruise and let the blood come out to show them”.[20] This gut wrenching sentence was a testament to the police brutality endured by Hamm and other Black males while being unjustly incarcerated—he being one of the eldest, nineteen years young. He had to take this intense measure, opening up a bruise, to reclaim his humanity and get medically treated for his injuries. Reich had access to this testimony in a facilitated exchange with the civil rights activist, writer, and curator Truman Nelson.[21] By removing the context and applying auditory distortions to the words “come out”, the history was lost, and capitalized on by individuals who would further Daniel Hamm’s erasure from the collective consciousness—individuals such as De Keersmaeker. The appropriation by adé Soleil of movements from Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich and of techniques applied in the work Come Out was an attempt to take back what has been lost—a voice, a place in the collective imagination, legitimacy—while bridging the past and the present. More than fifty years later such narrative is still an intrinsic part of collective fear, loss and anger. Moreover, adé Soleil contracted an ASL interpreter to translate while he was reciting his revised version of the looping piece Come Out. He explained that sign language is a choreography in itself that has the power to amply what is linguistically difficult to communicate, and in this case it added a visual language to Black male experiences, in order to tap into embodied memory.[22]

Sandra Vida: Vigil: Field of Crones with Lillian Allen, Anne-Marie Bénéteau, Cat Cayuga

Vigil: Field of Crones opens with Sandra Vida mapping onto the theatre floor the four cardinal directions with the aid of a compass. She then proceeds to sweep away conflicting energies with a besom, before casting a protective salt circle. A projection of a waterfall appears to further assist the artist in preparing a sacred and meditative space. A stool is placed at each cardinal point, and a cauldron is positioned in the middle of the circle. Vida disappears for a short moment and re-enters the room with three other women—Lillian Allen, Anne-Marie Bénéteau, and Cat Cayuga—in a ceremonial line. Dressed in grey and silver, they seem to belong to the same coven, “the Sisterhood of the Crones”. Once they all sit at their respective cardinal direction, Vida presents her partners, informing the audience about the bond they share. These four women, the crones, supported each other twenty-five years ago during the fight for the implementation of racial and cultural equity practices within Canada’s artist-run centre network. In 1993, the mother of Canadian artist-run organizations, ANNPAC/RACA—Association of National Non-Profit Artists Centres (ANNPAC) /Regroupement d’artistes des centres alternatifs (RACA)—unravelled due to a failure to fully commit to anti-racist initiatives and better practices to support racialized artists proposed by Minquon Panchayat.[23] Each of them, Vida, Allen, Bénéteau, and Cayuga, occupied different positions at that time, but they crossed paths during their activism in restructuring and reshaping the artist-run cultural landscape. A piece of dry ice is placed in the cauldron creating a beautiful fog effect, heightening the mysticism of the performance. The archetype of the crone is important as a catalyst to reclaim the place of age-accumulated knowledge within the framework of institutional memory. Vida cleverly plays with tropes embedded in the distorted definition of the witch/crone by generating a mystic production, while inviting the audience to meditate on the legacy and ongoing invisibility of women’s labour in the arts. As institutional memory tends to easily forget and the intergenerational gaps deepen, it is crucial to recognize and name the people who have been and are still working against systemic barriers, ensuring a brighter creative future for all. More importantly, it is vital to enounce that past claims are very similar to present frustrations. The status of the crone is one to be reclaimed and appreciated. They have paved the way for emerging practitioners like me, passing the baton so that we can build on their legacy, and push for sustainable changes.

(F)NOR: Exhausted

Standing outside on a chilly Sunday afternoon, the members of (F)NOR—For No Other Reason—Donna Akrey, Andrea Carvalho, Margaret Flood, and Svava Thordis Juliusson, assumed the positions of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon as per Picasso’s seminal work. Painted in 1907 and exhibited for the first time in 1916, this painting has been analyzed again and again by art critics and scholars. In popular culture, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon signifies a ground-breaking approach to feminine forms and innovative techniques. Post-colonial and feminist readings that are critical of “primitivism”, cubism, and the role of the female subject are fairly new. This piece by (F)NOR articulated questions that I have kept to myself in art history classes, which resurfaced while watching this tableau vivant. Exhausted exposes the physical labour inherent in producing preliminary sketches on which a masterpiece is created. Apart from the speculation about their social status, the history of modeling as a profession as well as the relationship between artists and sex workers, I have not yet encountered the details about the ways Picasso contracted the sitters, their working conditions, and relationships among them. What were their names? How were they approached to perform in this way? Did they model for other painters? What was their compensation for their labour? How many sittings did they have to go through until Picasso was satisfied? For how many hours did they maintain their poses? Sustaining the same detached and cold stare as in the painting, the performers didn’t return the viewers’ gaze. Wearing colourful costumes with prosthetics to suggest the desired cubic forms, they appeared bound by their apparel, making the exercise harder. Moreover, their attire with contrasting colours made them simultaneously hyper visible and invisible. Their presence intrigued the passers-by, however their inactivity rendered them quickly unexciting, and thus their labour was easily dismissible—like the sitters featured in the Demoiselles d’Avignon. Assuming their respective poses, with time they grew more and more tired, they had to stretch and release muscular tensions, support each other to stand, rest their arms, legs, and necks to the point that they were no longer respecting their positions, but listening to their bodies. I stayed about 40 minutes straight watching them, standing. Each minute seemed like an eternity, and I couldn’t help but wonder about the stamina needed to perform for four hours, staring into emptiness. I wanted to stay as long as I could as an acknowledgment of the physical and emotional toil involved in this durational performance, and the erasure of the original sitters’ work.

Louise Liliefeldt

Species. The term species is loaded, especially because of its interconnectedness with capitalist and present social orders. Spray painted in orange on a potted tree and later on the back of her black t- shirt, Louise Liliefeldt uses the word to tackle the tension between feelings of superiority and guilt, more specifically when thinking about the established relationship between humans and non-humans post Western Enlightenment. Although a great deal of the artist’s critique is focused on the Victorian values of humans versus nature, it also points a finger at how one’s humanity can easily be stripped for capital gain, and so one of the questions that Liliefeldt asks with this performance is: what do we do to what we think is lesser than us?[24] The choreographed movements highlight this thought, more precisely with the focal point being the excessive pruning of a tree. A tree that has been created for the purpose of a controlled environment, manicured for an indoor space. The artist goes up and down a tall ladder, initially only cutting off dry leaves. Then she moves to the ones that are simply imperfect. At the end, it is as if it has become an ingrained behavior, an impulse that she can’t stop; even the good ones are discarded. To add to the uneasiness of this piece, she also utilizes stasis midway into an action, forcing the audience to pay attention, to be fully present, to witness each movement. Furthermore, a visually strong Christian symbol of discipline, guilt and penitence is added to reinforce the idea of redemption after the fact. In a darker corner of the room, an orange light glows; it is the same colour as the painted word “species” on her back and on the pot of the plant. Kneeling down, she flogs herself with a whip with leather fringes. Each time the artist passes another pruning stage, a sort of point of no return, she flogs herself out of guilt. The self-inflicted violence echoes the one permitted on the tree. Tiredness and ache are immanent in the piece, as the muscles are memorizing a demanding movement sequence, pinning down the tremendous length that goes into maintaining and sustaining a distanced rapport with nature. Who is physically maintaining this order with sweat and blood and who is it benefitting? Whose bodies are compromised when thinking about imminent climate change? At the other end of the visual spectrum, an ostrich egg, that was hung on the tree and later carried on her back, is finally entrusted to the care of the audience. We pass around the egg carefully, attentive to the desire to extend a tender gesture that was nonexistent in the space.

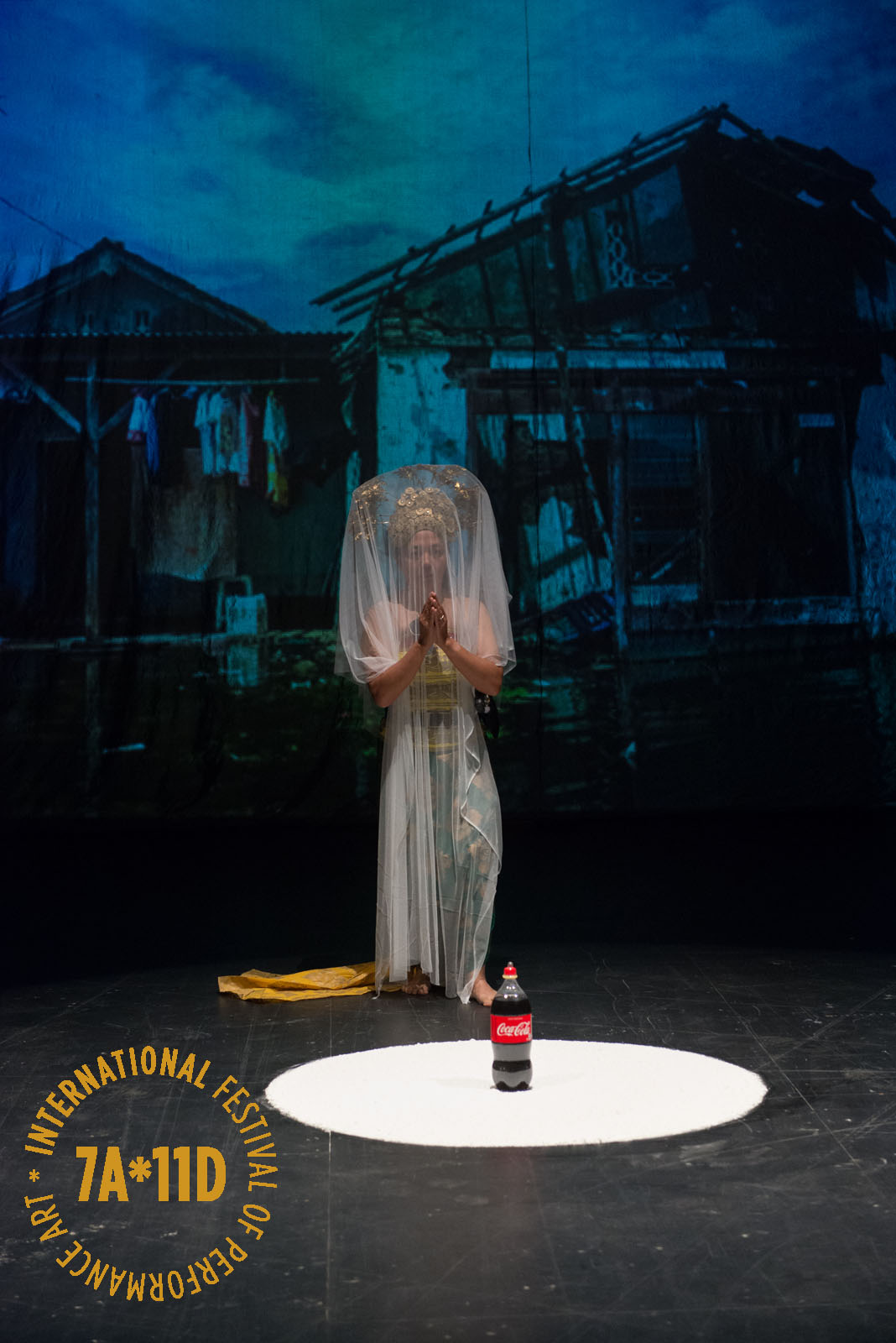

Arahmaiani: Handle Without Care

Buddhist chants from the Gelugpa sect (also known as the Yellow Hats) fill the theater with a reverent atmosphere. A powdery white circle has been traced in the middle of the room; a Coca-Cola bottle with a condom on its end is standing in the middle. Arahmaiani appears wearing a recognizable traditional Balinese gown, complemented by an intricate golden headpiece and a long meshed veil. Moving at a slow pace, she walks on the outer edge of the white circle while holding a few lighted incense sticks. In the background, images of individuals living in poor conditions in the slums of Jakarta are projected in a loop. The soundtrack transitions from solely mantras to a hybrid audio mix incorporating the musical piece Miserere mei, Deus, composed by Allegri, and the Islamic chant Al-Waqi’ah, from Al-Qur’an.[25] By interweaving these diverse expressions of faith, she illustrates the close proximity and the complexity of cultural cohabitation in Indonesia, and how it extends in her life (as a Muslim Javanese, who embraces Buddhist principles and collaborates with Jesuit priests in Indonesia and Germany). One could also perceive the chosen soundscape as an indicator of the present electoral landscape, wherein religion plays a pervasive role in the presidential campaigns. The tensions arising from this political climate put at risk the well-being of many groups of individuals, notably the Chinese Catholic minority, women, and LGBTQ2S+ community. In a choreographed sequence drawing from traditional Balinese dance movements, the artist removes her veil and morphs into a defender/warrior who fights against invisible and yet omnipresent threats. The condom on the bottle is a metaphor conveying an attempt to contain the casualties of neo-colonial practices via global capitalist ventures, such as the massive deforestation and extraction practices for the export of goods (such as palm oil in Indonesia), the hegemony of popular Western culture and the tourism industry.[26] Armed with a long blade called a keris or kris in Javanese and Balinese culture, she moves in circular motions. Then, from the shadows small army toy tanks appear, firing at her and the audience. With a decorative toy gun and a light sabre, the artist is now waging war against a visible enemy. Here, religiosity and mundane materialism are entwined as an inevitable social relation fuelling culture wars. Via this multi-media work, the performer invites the spectators to be attentive to the ones who are caught in between these systems and handled without care.

Handle Without Care was presented for the first time in Bangkok in 1997. Through this work Arahmaiani has amplified the voices of vulnerable communities with whom she has been living and working. Interestingly enough, the artist mentioned that since last year this piece has been in demand again, responding more than ever to the global socio-political climate.[27] The artist has lived in the slums and villages of Jakarta and Yogyakarta, where she became an active and engaged community member. For the past decades, Arahmaiani has focused her energy on denouncing class, religious, and gender-based injustices as well as the cultural consequences of colonization, and subsequently the tourism industry in Indonesia. More recently, she has expended her socially engaged practice in the Tibet plateau, collaborating with monks and villagers emphasizing environmental sustainability.

Gustaf Broms: the unknown history of a forgetful amnesiac

The unknown history of a forgetful amnesiac investigates the ongoing legacy of the Cartesian mind-body dualism which informs the intellectualization and classification of the self as well as the limitations residing in the concept of being—existing as an entity that is fluid, belonging to earth’s biodiversity and universal energies. Gustaf Broms suggests in his piece that the compartmentalization regulating Western thoughts and knowledge-making has induced a collective amnesia, one that perpetually forgets that nature is not a separated entity to exploit, tame, or romanticize. On stage the artist’s examination of his personal, and by extension our collective amnesia, begins in the enlightenment era. The room is silent and dark; Broms walks in with a silver metallic suitcase. He opens the suitcase and carefully lays out a piece of cloth, an assortment of glass bowls, flasks, beakers and a candle. Some of the vessels contain natural elements such as water and soil. The metallic suitcase is now suspended on a fishing line, swirling in the air. Projections featuring a night sky (filmed from the artist’s home) followed by a compilation of astrological and astronomical images of late 18th century encyclopaedias are reflected onto it and on the back wall. This setting immerses the spectator in an atmosphere recalling the private scientific demonstrations held during this period. A vessel with oil is lit on fire, and the fire is extinguished with water. His interaction with the organic components is contemplative, and literally playing with the tropes of dualism. The artist comments, “I look at the use of the elements fire, water, earth and air, as a way to have the work anchored in the organic/biological, as a starting point, before the intellect creates its abstractions, the symbolic existence of mind.[28] The projection slowly changes to black and white images of the artist’s hand gesticulating, with a selection of imagery from dictionaries printed in the 1950s collaged onto them. To further his exploration, he rubs his face and hair into the mixture as if to make one with the organic material. An audio record sounding like a primal call to the self is playing. It appears as if his subconscious is piercing through the conscious, attempting to communicate forgotten knowledge. He responds to the call with a microphone, echoing the original source and creating another layer of sound. Broms pushes one step further into finding his way out of forgetfulness by refusing the language that has been an impediment to the re-imagination of the self; I AM MAN, I AM NAME, I AM NATION, I AM COUNTRY, I AM BODY, I AM BEING, I AM, I. After this segment, he moves to the opposite end of the room and dresses in a costume made out of natural matter such as dried plants. As he dances to exorcise the recollection of his limitations, and ceremonially invoke transcendence, he is momentarily transported to another plane, one that is distant from the spectators—perhaps there, he remembers his essence…

François Morelli, Mari usque ad Mare/ D’un trou d’eau à l’autre/ Piss and Vinegar

Mari usque ad Mare/ D’un trou d’eau à l’autre/ Piss and Vinegar was a Toronto adaptation of the performance Tidal Walk/Marche Fluviale presented at the VIVA! Art Action festival in Montreal. The work was conceptualized for the city’s 375th anniversary. For the first presentation of the work, François Morelli chose six fountains that are markers of Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal’s ongoing colonial histories and genocide of its rightful custodians: Maisonneuve Monument, Vauquelin Square, Place Jean-Paul Riopelle, Victoria Square, Cabot Square, and Place Marguerite-Bourgeoys.[29] In Toronto, Morelli played with similar themes and props. Eight fountains were selected with the aid of the 7a*11d team, tracing a path from east to west, echoing the Canadian motto Mari usque ad Mare, translating as From Sea to Sea. The use of the national motto questions our ocean areas of jurisdiction in ensuring national security, sovereignty and defence. Bordered by three oceans, Canada’s economy, environment and social fabric are inextricably linked to its coastline. Mari usque ad Mare was spelled in front of Toronto’s City Hall with sandals that he collected on a beach in Alibag, a city close to Mumbai, India. Altered by the sea water, hinting at their long journey, they exemplify a transcontinental interconnectedness, the ocean as a ruling global transportation system. The plural symbolism regarding water as a placeholder connecting global socio- economic histories become also a central figure of colonial encounters. Furthermore, the sequence “d’un trou d’eau à l’autre” is a subtle French wordplay referencing the Trudeaus father and son,[30] and perhaps also today’s concern with the Navigable Waters Protection Act (NWPA).

Starting at dawn on a rainy day at St. James Park, Morelli subsequently spent about twenty to forty minutes at each chosen site: The Dog Fountain, Commerce Court, Nathan Phillips Square, South African War Memorial, Glenn Gould Place: The Eternal Flame of Hope, Massey Harris Park, to finally arrive at Lisgar Park, across from the Theatre Center, at sunset. Each fountain/site was explored differently; the artist would survey the space horizontally and vertically, and sometimes wear a mask made out of a small beige leather backpack, rendering him beast-like. In his reflection, the separation of human and animal is also reconsidered and blurred, making room for interspecies connectivity. Morelli is interested in the ways in which one occupies space in connection with the histories embedded in the landscape and the surrounding ecosystems. During his travel from one site to another, the mask—resting on a crutch and pushed on a small cart—became an accomplice, a companion, a being to care for.[31] As a final act, Morelli wore the leather mask and attached the crutch, which was extended with a paintbrush, around his neck. This elongated paint brush was dipped in piss collected throughout the day mixed with vinegar and bottled water from the oldest water source in Banff. This peculiar liquid worked as a medium to draw onto the ground in the dog park, interconnecting the elevated act of drawing with animal territorial markings.

Dariusz Fodczuk: publicly yet privately

publicly yet privately was an interactive and participatory art experience presented in three acts. Between each mise-en-scène, artist and 7a*11d collective member Tanya Mars would read instructions to the audience. Although we were informed about the expectations in terms of how to move in the space, it was never clear what was awaiting us once there. Each time, it was a surprising event, sometimes dependent on the audience’s interactions. The work was facilitated in a way that conveyed an orderly chaos, one that implied an active interconnectedness between all of the individuals sharing that moment at that time. The first tableau was constituted of five or six wooden tables on top of which objects such as bottles of wine, glasses, buckets, dishes, pots and pans, and other familiar household items had been piled. I believe that the arrangements were intentionally fashioned to look simultaneously precarious and imposing. Black ropes were attached to one leg of each table, and laid on the floor in a straight line. The idea was that members of the audience would pick up the ropes and pull on each of the tables. Thus, a number of participants came forward, each holding a cord and pulling the tables at the same time, but at a different pace depending on their constitution. With all of the items falling and shattering on the ground, it was an exciting event, and to be honest, it was very satisfying to witness an inconsequential destruction of goods. After this first piece, we were asked to wait in the hall for the second part. After this striking piece, one could only wonder what might await us in this round. Hidden behind the tables that served in the last performance, Dariusz Fodczuk was aiming at the theatre’s walls, with a paintball gun loaded with white paint contrasting the black coloured “canvas”. Standing in the middle of the chaos from the first act, the crowd was left to make what they would of what was unfolding before their eyes. At first the intentions were not clear; it appeared as though the artist was aimlessly shooting the wall, when in fact the word LOVE was being spelled out, like a small relief in a disaster zone. The third act functioned as an emphasis to the previous tableaux, one that could only be accomplished with the viewers’ participation. The role of the audience members was ever active, fluctuating between performer, witness, and art medium. Directed to lie on the ground along with the sparse traces of the previous acts, we were invited to touch our neighbour on our left, either on their arm or feet. This orchestrated intimacy generated an awkward but amicable connection among a group of strangers. Fodczuk walked around with his phone camera on, the image projected on a wall, reflecting back this assembly of bodies as they gradually become one with the work itself.

Hank Bull: The Red Jewell, Another Thrilling Episode in the Timeless Saga, Donkey Tales, as Told in Shadow Play by Hank Bull

Introduced by the charismatic Momo, The Red Jewell, Another Thrilling Episode in the Timeless Saga, Donkey Tales was a shadow play presented by Hank Bull in collaboration with Arthur Bull, Bob Vespaziani, and Rhiannon Collett.[32] Bull has been exploring Shadow Theater as a performative medium since the 1970s. At first it was purely practical, mainly used to render visuals for sound projects made in collaboration with Patrick Ready. Their exploration expanded to multimedia performances inspired by late 19th century Western shadow play. To broaden his knowledge and techniques he (and traveling companion Kate Craig) attended performances in India, Thailand, and studied in Bali under dalang (puppet master) I Wayan Wija.[33]

The Red Jewell was a sort of delirious philosophy class, brushing on themes such as desire, free will, self-actualization, and the cogs of modern society. The viewers were encouraged to walk around the set and observe the inner works of the performance through all of its angles and finest details. Granting access to small gestures such as the handling of a silhouette, the facial expressions of the artists and musicians, as well as the transition of instruments for sound effects, eliminated the division between the performers and the spectators, making the stage an immersive moving sculpture.

The Donkey, the main character of this piece, belongs to a long line of literary and philosophical traditions wherein the quadruped is employed as an allegory for human nature. Exploring the power and entrapments of free will, he wanders, experiencing all sorts of internal dilemmas. For example, exhausted and starved, he succumbs to the pressure of choosing between two lush bales of hay, deciding to die of hunger rather than making a decision. Later on, he stands up against an abusive employer who coerces him into labouring for free. Finally, he decides to leave everything behind to pursue the quest for knowledge and pleasure with his loyal friend, the Dog. Boarding a boat on the open sea, they fall into the abyss, a liminal space, a “symbolic second death” as put by Bull.[34] This moment in limbo is the point of rebirth; it is the prophecy of self-fulfillment. After passing through the abyss, the protagonist and his sidekick land in Paris, France, where the Donkey makes a flamboyant entry in the art scene through his brilliant panting, the Red Jewell. Through this tale, Bull offered an odyssey wherein live music, humour and absurdity intrigue the adult and entertain the inner child, carrying them to a parallel dimension, a magical elsewhere.

[1] Mathieu Lacroix in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[2] Erika DeFreitas in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[3] Erika DeFreitas encountered the play Objects Lie on a Table (1922) by Gertrude Stein through her participation in the group exhibition, Rehearsal for Objects Lie on a Table, curated by Emelie Chhangur at the Art Museum of Toronto in 2016. Pages of the play were shared via email on November 12, 2018.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Excerpt from DeFreitas’s original work. Each sentence occupied one page. Erika DeFreitas, email communication with the author, December 20, 2018.

[6] Thirza Cuthand, email communication with the author, January 7, 2019.

[7] Ibid.

[8] James Knott in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Halberstam, Jack, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), p 2. (This book has been published under the name of Judith Halberstam.)

[11] James Knott in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[12] Cindy Mochizuki, email communication with the author, November 5, 2018.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. In our correspondence the author revealed that although it was off by a few days, she picked a performance that related to the month that we were in and the kind of offerings that take place in the autumn.

[15] Ayumi and Peter found out that T’karonto means the “trees in the water”, and they were thinking about becoming the trees in the water. The gold leaf as a signifier of the season we were in, the autumn, the beauty of the leaves falling from the branches (our arms), gold as skin, as resources, as value, as a shining element. It was important that this gold skin fell off into the water, as part of their offering to the water and the land. It also signified the estrangement of putting a monetary value on a human-carved place for the signing of Treaty 13, and what it has led to (pollution, strange lines of travel). Ayumi Goto, email communication with the author, November 7, 2018 and Peter Morin, email communication with the author, December 17, 2018.

[16] Peter Morin, email communication with the author, December 17, 2018.

[17] Ayumi Goto, email communication with the author, November 7, 2018

[18] Peter Morin, email communication with the author, December 17, 2018.

[19]Ibid.

[20] The story of the Harlem Six is a narrative of Black male teenagers and young adults—Wallace Baker, Daniel Hamm, William Craig, Ronald Felder, Walter Thomas, and Robert Rice—wrongly convicted for the murder of a white couple who were shop owners in Harlem. Daniel Hamm’s statement is from an interview he did with Truman Nelson after his first night in a police station for the little fruit stand riot, in 1964.To learn more about this story see James Baldwin’s article “A Report from Occupied Territory”, published in the Nation magazine in 1966.

[21] Nelson sought out Reich to help him edit several tapes with interviews featuring the Harlem Six, their mothers, and the police, in order to write The Torture of Mothers and support legal procedures. In exchange for his labour, Reich asked that if he found something interesting, he be allowed to use it for his art practice. The resulting sound collage Come Out was used to help raise funds for the Harlem Six’s retrial, but mainly became Reich’s big artistic break. See Brent Hayes Edwards, Epistrophies: Jazz and the Literary Imagination (Harvard University Press: Cambridge MA & London, England, 2017), p. 246.

[22] Barak adé Soleil in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[23] Minquon Panchayat was a council composed (at first) of six regional representative member positions (later looking for more 8 more) within ANNPAC/RACA’s Management Committee, and these representatives were from existing collectives, organizations, or artists and cultural workers from marginalized communities. Their goal was to focus on offering to their constituency a seat at the table, to be part of the decision making within the artist-run culture. They deployed a strategy for institutional change via financial lobbying, programming, and renewing the national artist-run network with relevant institutions that sustain an anti-racist agenda. To learn more about their initiatives, and the impasse reached with ANNPAC/RACA as well as the subsequent initiatives, see Clive Robertson, Policy Matters: Administrations of Art and Culture (YYZBooks: Toronto, 2006), p.25-43

[24] Louise Liliefeldt in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[25] Arahmaiani, email communication with the author, December 11, 2018.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Gustaf Broms, email communication with the author, December 8, 2018.

[29] François Morelli in discussion with the author, November 2018.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Arthur Bull (guitar), Bob Vespaziani (percussion), and Rhiannon Collett (volunteer-assistant).

[33] Hank Bull, email communication with the author, December 3, 2018.

[34] Ibid.